I mentioned my visit in post-148 (“the Gettysburg of Korea“). I wrote:

In 2012, after reading “The Longest Winter”, I identified the location of the battle by figuring out its current name. What we wrote in English in the 1950s as “Chipyong” is now written as “Jipyeong” [Gee-pyuhng] (지평리 in Korean). Its suffix, ri or ni, means “village” in Korean. It has since been promoted to “myeon”, a slightly larger settlement than a ri/ni. The current name is thus Jipyeong-myeon (지평면).

[…] [Visiting the site] was one of the most significant excursions of my time in Korea. I feel blessed that it worked out the way it did. The word “Chipyongni” does not even appear in the tourist guidebook I have. It was something I independently discovered.

One of the amazing things about this excursion to Chipyongni is that I covered 95%+ of the distance to the battle site (the red marker above) using what is loosely called “the subway”. It has evolved into a cheap-and-easy Greater Seoul Rail Network. It has been gobbling-up legitimate (above-ground) train-lines for years, and continues to expand. There are now about twenty lines. I wrote about one such rail-line way back in post-9:

This rail line [“Gyeong-Hui”] still exists intact, today, It was incorporated into the ever-growing Greater Seoul urban rail network (still often loosely called a ‘subway’) in 2009. I remember when that happened, as I was living in Ilsan at the time, through which it passes.

Yongmun Station, September 2013

Yongmun Station, September 2013

Saturday. Sometime before 10:00 AM, my traveling companion and I arrive at Yongmun Station, tired, groggy. For an “end-of-the-line station”, the atmosphere outside is downright “kinetic” this morning, though. Koreans in hiking gear are frolicking about. They are probably all going to the Yongmun Temple area.

In the 850-page travel guidebook on Korea I have, this entire region (Eastern Gyeonggi-Do) gets about a page and a half’s write-up. All that is mentioned is Yongmun Temple and its environs (“Yongmun-sa [temple] sits below Yongmun-san [mountain]. At 1,157 meters, this mountain is not the tallest in Gyeonggi-Do, but some say it’s the best-looking. Of its many hiking trails, the one that’s perhaps most often used goes over the….”). A few resorts are also mentioned.

In that guidebook, the word “Chipyongni” appears nowhere., though.

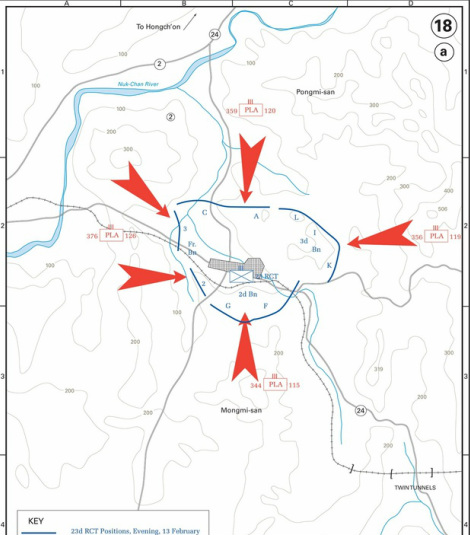

The original idea was to get out of the train station at Yongmun and proceed to Jipyeong on foot, only three miles away. I carried printouts of the battle history, downloaded from history.army.mil, which I read again on the train ride. Included was the following map:

Off to the west, along the railroad tracks and just off the map, is Yongmun Station. [See post-147 for battle history]

Walking through the town of Yongmun, we got some kimbap and a disappointingly-small plate of tteokpokki (떡볶이). Heading east towards Jipyeong, I saw a ROK Army base:

Minutes later, we were out of the town, and came upon this kind of scenery:

A snag in my ad-hoc plan presented itself after a while. It was necessary to cross a narrow mountain pass, but construction workers were obstructing it. We turned back. A taxi passed by, and we got in. I marveled at this good fortune. A taxi passing by such a road was lucky, exactly when it was needed. The friendly driver drove us the few miles to the Chipyongni Battle Memorial, dropping us off in front of the below sign. The ride cost 5,000 Won ($4.50).

Here are some photos of the memorial:

The building shrouded in blue will be a new museum. I found this sign in front of it:

I spent a long time at the memorial. I read every word, though I already knew the history from my previous reading on the subject. As I hope the above pictures show, the atmosphere at this memorial site is very pleasant. There were no other visitors or passersby in the hour or more I was there, though I did see one construction worker.

The red banner there says “우리도 죽기전에 지평면에서 수도권 전철 타고 싶마”. I recognized enough words to understand that it was a slogan demanding that the Seoul urban rail network be extended to Jipyeong Station. It currently ends one station before Jipyeong, at Yongmun. This is a major inconvenience for Jipyeong residents. If they want the ultra-cheap way to get into and then around Seoul (see above), they have to go to Yongmun first. They can still ride the “normal trains”, but those are much more infrequent and more expensive. Maybe a bigger reason for this campaign is to put Jipyeong “on the map”. To Seoul-area dwellers, Jipyeong doesn’t exist. If it’s on the subway network, suddenly it exists, and more people would visit, and would spend money. These banners were all over Jipyeong.

Here is a wider shot of the intersection:

This boy’s warm conversation, and (futile) attempts to help, was the first of many instances of kindness from Jipyeong people that really impressed me (the taxi driver was first, but he was a Yongmun person, I think. He undercharged me, knowing I was a foreigner visiting this historic site). Random “street” kindness to strangers, especially foreigners, is quite uncommon in Korea, and this boy’s kindness amazed me. Never once in Bucheon, in two years, has anything like this happened to me.

Continuing on, I resolved to try to find where the railroad crosses the major road east of town, that being where the 23rd Regiment’s 2nd Battalion was entrenched, according to the army-history map. I never made it that far. Walking a short was east, I found a town-hall. I had the idea to look for a map, but it was locked up. A bunch of men were loitering outside an adjacent building, and invited us in to eat. It was a dining hall. Before we knew it, this happened:

So the guys standing outside the town-hall insisted we should eat this free food. Bottled water was also given freely, and there was even beer. The man in the blue baseball cap in the above photo came over and talked to us for a long while. He insisted on sharing some beer. The subject turned to the battle. The man consulted my map (this one), but held it upside down. He talked at length, my Korean friend reported, about the site of his house and how many Chinese were killed in its vicinity. He said he’d been in the USA in 1988, while in the ROK military. Another local, a man with tied-back hair who greatly resembled an American-Indian to me, also sat down, mostly quiet (his taciturnity added to the “American-Indian vibe”). He was clearly interested and wanted to help.

Soon the man with tied-back hair asked if we were interested in the small museum about the battle. It was housed in the nearby library. We were. It wasn’t open. The man with tied-back hair said to wait a minute. Minutes later, the man returned, and led us to the library adjacent to the eating-hall and the town-hall. He’d gone to fetch the octogenarian Korean-War veteran museum-caretaker. He asked him to open it on account only of us! The old man had kindly come in, and was waiting. I couldn’t believe my good luck to meet such people as these. (This kind of hospitality puts Seoul and its satellites, like Bucheon or Ilsan, to shame. It made me think, “I hope this place fails to get its train station incorporated into the Seoul Metrorail network”, for fear it would be corrupting.)

A small room constituted the Chipyongni Museum:

There is Korean War paraphernalia of all kinds, uniforms, helmets, equipment salvaged from the battlefield, badges, portraits, photographs, books, maps, and binders filled with photos of the various commemorations over the years. Every year, he told us, a French delegation arrives to honor the French battalion. Descendants of the American veterans also come every year, he said. The man informed us of various fine points the history of the battle (it involved only 300 Koreans, “KATUSAs” embedded in the U.S. Regiment and the French battalion, he said), of the village (it has not really grown much since 1951), of the museum (the new, larger, museum [see above] supposedly opens in 2014, but he doubted it would), and the preservation efforts (he said there was talk of making some or all of the defensive perimeter into a marked hiking path. It would be two miles long or so). This man has documented a lot about the battle. I get the feeling that the new museum, next to the memorial, may have been his initiative.

I noticed the guestbook on the table. When I visited on the afternoon of September 7th, there were no names in it yet for September. In fact, the previous entries were on August 20th, and prior to that, August 11th. I leafed through all the pages, going back to early 2012, and found only a small handful written in English, and those belonged in all but one case to U.S. Military personnel. They wrote their “address” as “Camp Humphreys” or the like, nothing more. There may have been about five military who visited. There was a single non-military foreigner in the past year, the man recalled. He said she was a middle-aged woman from Texas visiting her daughter who was teaching English in a nearby city. He described her.

I signed the guestbook, leaving my name and address.

At the end, the kind and energetic man gave me two pamphlets about Chipyongni in English and Korean, and a medallion that says “We Will Not Forget / Battle of Chipyong-Ni” and something in Korean.

After leaving the museum, we walked to the train station to get tickets on the “normal train” get back to Bucheon, with the intention of also finding some of the other historical markers the kind old man at the museum had discussed.

Another act of unprovoked kindness followed at the train station. The attendant said no seats were available, but that we could come back later and maybe some would open up via cancellations. Someone in Seoul or Bucheon would’ve just sold us “standing tickets” (the same price, for some reason, as sitting tickets) and been done with it. This man, though, waited, and constantly monitored the status of seats available via his computer. He tracked us down outside the station an hour or more later and said he’d reserved the tickets. We paid. We rode back to Seoul that evening in seats, and fell fast asleep (having woken up at 6:00 AM), which would’ve been impossible with standing tickets. Why did this man go so far to make our trip more convenient? He gained nothing from it. These Jipyeong people are amazing, I concluded.

Before leaving, I found a few more historical markers. The French memorial is near the train station:

I suspect that these memorials were set up by the Americans because of the grass. Both here and at the main battle memorial (discussed above), the grass is of the softest kind you often find on American front-lawns, not unlike my memories of my mother’s front lawn from years ago, so soft it’s more pleasant to lay on than a bed.

Judging by my comparison of the current map and the battle-history map, this was probably the above was about the view the French soldiers had as the Chinese approached and attacked.

This is a very informative and interesting description of your visit to this important site–and enhanced by the beautiful photos. Your comments remind me of something I heard from an American working in South Korea when I was visiting there many years ago. He said that South Korea was like two places: There is Seoul and there is the rest of South Korea. Maybe it is still at least somewhat true all these years later.

My coworker Jongsun (who helped me a lot in those days) also said something like this to me when I was new to Korea. He had a negative view of “Seoul people”. I don’t know what that Peace Corps man meant in 1970, but I think Jongsun viewed the Seoul-Person archetype as decadent, frivolous, greedy, and selfish. That was 2009. Later that year, he moved down south to work in some kind of pharmaceutical company.

That kind of kindness of countryside people is also considered as “정”. In fact I think that might be the essence of it. Koreans usually say those suburban people has more of it. Sadly it is true city people don’t and are not able to have it among each other nor toward strangers. The bigger the city is, the colder it would be. It is not something unexpected but still a bit sad.

It’s true what you say about urban vs. rural attitudes anywhere in the world. I often think about how it may be different in East-Asian, or Korean specifically, vs. other places.