In my class are two good-humored Greeks I think their mid 20s. One spent a few years in the U.S. as a boy.

This week and next, the teacher’s topic for us is the final year or so of the German Democratic Republic (fall 1989 to fall 1990). Their system, in retrospect, was showing serious signs of strain by August and September 1989; the anti-communist silent protests centered on the Lutheran churches had been ongoing for years Leipzig and Dresden but began to mushroom in October 1989.

The marchers’ two principal chants were “Wir sind Das Volk” [‘We are the People,’ an odd slogan in some ways; some today, long after the days of communist rhetoric, may not realize that their slogan deliberately mocked communist rhetoric about “the People”] and “Gorbi! Gorbi!” Gorbi” [Gorbachev, seen as a savior]); the Berlin Wall was opened by the authorities on November 9th, 1989; the GDR formally continued to exist for another eleven months and held an election which featured a young Angela Merkel as a candidate for the first time; she attached herself quickly to the ruling CDU machine, =inherited this very machine later on, and has been Chancellor 2005 to present at the head of this machine — likely now through 2021, after the latest German election).

What was the “key point” in the dissolution of the German Democratic Republic? The state security services choosing not to suppress October demonstrations was clearly vital. October may already be too late a date, though.

Today the German teacher spent some time on the so-called Genscher Rede [speech] of September 30, 1989 at the West German Embassy in Prague. That is 28 years ago today. At that time, hundreds and then thousands of East Germans had camped out on the West German embassy grounds in Prague hoping for permission to emigrate to the West. The fact that the Czech-Communist security services allowed them to simply jump the embassy fences is another sign in retrospect that the end was near.

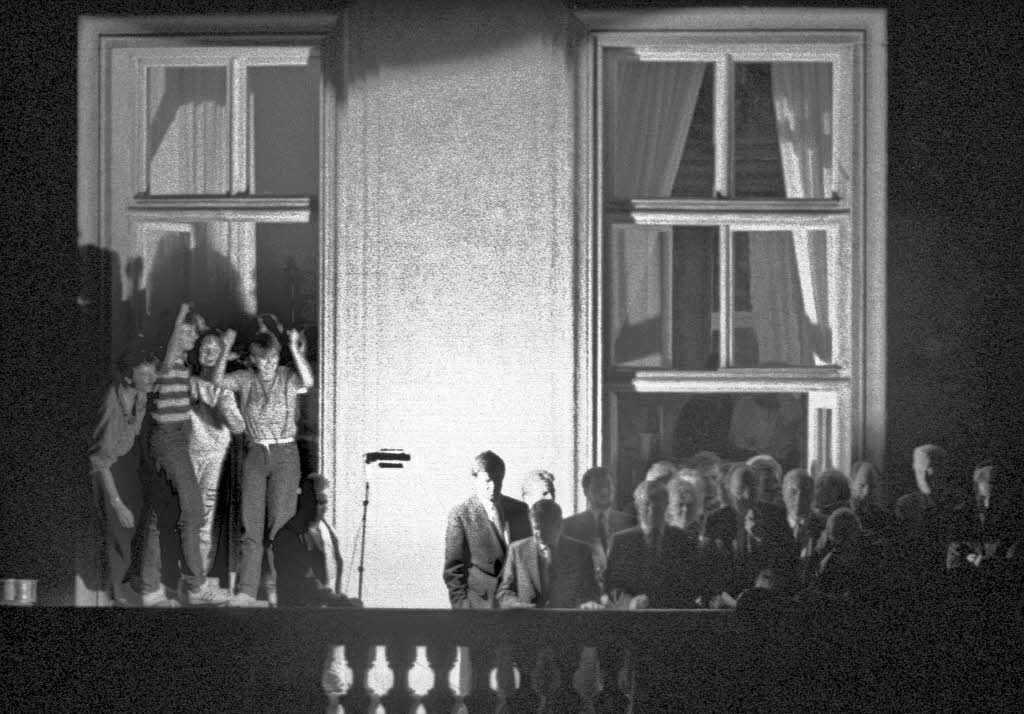

We watched the speech. Genscher’s “speech” was just a few seconds long and delivered in a mood reminiscent of a team winning the World Cup.

Genscher gave the speech on the embassy balcony overlooking thousands — some youths (above left) seem to have climbed onto the window sills or balcony to hear it.

This is how a Wiki writer describes Genscher’s speech:

“He announced that he had reached an agreement with the Communist Czechoslovak government that the refugees could leave: “We have come to you to tell you that today, your departure …” (German: “Wir sind zu Ihnen gekommen, um Ihnen mitzuteilen, dass heute Ihre Ausreise …”). After these words, the speech was drowned in cheers.”

Genscher rose to West German Foreign Minister and Vice-Chancellor (1982-1992) under Helmut Kohl and was previously West German Interior Minister (1969-1974) under SPD Chancellor Willy Brandt). He rose in politics within the Free Democratic Party (FDP), a freemarket-liberal party. In the old days when West Germany’s CDU was still widely considered primarily a “Catholic Party” by Germans, the FDP was a safe place for Protestants on the right. (Almost all pre-communist ‘East Germans’ were, at least nominally.) Genscher was a high government minister under both left- and right-wing governments.

There was an federal (Bundestag) election in Germany last weekend. I think two things can be said about the Genscher Speech legacy given the results of the election.

(1) The ruling apparatus and its system may not have been as unpopular as this kind of imagery suggests. The “necoCommunist” party called Linke (which is descended directly from the East German ruling party) got 18% of the eastern vote, and generally does even better than that at the regional level (generally 20-25%). See, e.g., Post-246: Here Comes Bodo Ramelow.

(2) Refugee Imagery and its Political Discontents. I know that today’s Germans have two political/historical memories of Germans-as-refugees: This case is one, this imagery of thousands crowding the embassy grounds in Prague and elsewhere in 1989; the other is earlier but even more important, I think, as it is a kind of ‘foundation myth’ of the Federal Republic [West German state] itself: Following WWII, tens of millions across Europe were homeless and many were expelled or could not return for some reason, i.e. refugees. This included something like 12 million Germans from points east of the GDR’s eastern border. These expellees formed a large part of the Federal Republic’s population.

These two memories may have been what impelled Chancellor Merkel to suddenly and without consultation announce an open-border policy for refugees in late August 2015, which soon saw 1.5 million Islamic refugees enter Germany. German birth rates are low and the refugees were mainly young and male: One estimate has it that this 2015-2016 refugee wave alone constitutes 10% of the military-age population of Germany; in one fell swoop. This decision seems to have caused a significant exodus of support from Merkel’s party, to the FDP and to a brand-new party to the right of the CDU. For the first time, the Bundestag has a party that threatens the CDU from the right. Their platform is dominated by: “Stop Merkel’s Refugee Policy.”

The new party, the AfD, which was co-led by a man (Alexander Gauland) who left the CDU after forty years over the refugee crisis, did very well in the eastern states, even coming in as the largest party in some districts and a strong second in most of the rest. (The ruling CDU got 27.5% of the vote in the east to the AfD’s 22%.)