|

스마트폰을 쓰지 않는 사람이 어디에 있을까?

자, 오늘 아침에 대한민국의 수도권 지하철을 타고 가고 있을 때는 다른 승객들을 볼 수 있었지만 앉아 있던 승객들은 나를 볼 수 없는 것 같았어요.무슨 작고 밝은 스크린 때문이에요. 우리 기차에 앉아 있던 승객들은 24명이었는데, 그때 꼭 23명이 스마트폰을 보기만 (96%) 했어요. “스마트폰 중독”이 있는 대한민국인은 많다고 하죠? 미국 지하철에 있는 스마트폰 습관 비교할 수 있어서 다음 단락부터 쓸게요. 미국큰 도시에도 지하철이 있기는 하지만 2014년에도 미국을 여행하는 어느 서울에서 온 한국인은 미국의 지하철 열차에 들어가자마자 놀라는 것이 있을 수도 있어요: 미국 지하철에 있는 승객들 중에 “종이”신문을 읽는 사람이 많고 “종이”책을 읽는 사람이 많군요! 스마트폰을 쓰는 지하철 승객보다 “종이”를 쓰는 손님이 거의 3배나 있던데요…! |

Where are the Non-Smart-Phone-Using People?

Well now, today in the morning, as I was riding in the Seoul area’s subway system, I could see the other passengers, but the others, seated, could not see me, it seemed. This was because of some small, bright screens. There were 24 seated passengers in our train car, and at that time a full 23 of them (96%) were only looking at their smartphones. They do say that in the Republic of Korea, there are a lot of “smartphone addicts”, don’t they. In the USA, smartphone use in the subway is very different, so let me write about it next. In big cities in the USA, we have subways too, but even in 2014 now, a Korean from Seoul who enters a subway car will immediately be surprised by something: A lot of the subway passengers in the USA will be reading “paper” newspapers and “paper” books! As I recall, something like three times as many people use “paper” in the subway [in the USA] as use smartphones….! |

Month: November 2014

bookmark_borderPost-249: Uneventful Thanksgiving 2014 (And, How to Say ‘Turkey’ in Korean)

On the plus side, I figured out the amusing meaning of the Korean word for “turkey”:

English? Chinese? No. No.

Strangely, even though the bird is native to North America, there is a Korean word for “turkey” that is neither a Chinese loan nor an English loan (by which I mean a Koreanization of our word “turkey”; it would sound something like “tuh-kee”). The Korean word for turkey is “

The Meaning

From comparing the Chinese characters, I see that “

I asked good old Mr. Google about seven-faced birds and he pointed me here: “Japanese turkeys have seven faces“.

So, there we have it: In Japanese and Korean, the bird we call “the turkey” is called “the seven-faced bird”. A website called Hiker’s Notebook claims that this odd name “is based the belief that the turkey changes its facial expression in concert with its emotional state.“Word History Speculation

I’m going to speculate that the Americans introduced turkey to Japan sometime after Admiral Peary opened the country in the 1850s, and when Japan started to exert economic, political, military, and cultural pressure on then-long-stagnant, increasingly-backwards Korea, from around the 1880s, this word (among many others) came with it. This seems to be a reasonable guess.

The Future of the Word for ‘Turkey’ in Korean

Knowing what I know of how Koreans are, though, I hereby predict that if turkey ever becomes popular in Korea, the English loan (“tuh-kee”) will quickly grow in popularity and either replace the old Japanese loan totally or find a way to co-exist with it. This has happened with chicken. The Korean word is “

bookmark_borderPost-248: Thinking About Germany and “The Left” Party

* 28 seats were won by Die Linke (successor of the East German Communist Party) [31% of seats]

[…] [T]he Linke “neo-Communists” are a majority of [the new] ruling coalition, so it’s only fair that their guy, Bodo, becomes the formal leader.

Those in the east voting for Linke are generally older people who actually lived as adults under the Communist East German government. Is this, then, a partial vindication of that system and its government?

Maybe. But hear this:

This leads me to ask: What is a conservative? If we hold all else equal,

maybe a conservative is one who wants [thinks he wants] whatever system existed, say, forty years ago (or some such number of years ago; the recent past), regardless of what that system was, whether it was considered left or right or whatever at the time.Thus I realized that we can speak of a secondary base of this party — smaller but noisier — in the form of belligerently left-wing youth p

rone to masked-mayhem and violence, the type that Europeans will know as “Antifas”, and their less-belligerent sympaticos. Their material was highly visible in most parts of Berlin (they don’t call it “Red Berlin” for nothing). But not in all parts. “Ganz im Osten” (as I called it — “in the deep east”) of that city they faced hostile territory and they knew it, or so I gathered. This territory belonged to the infamous Rechtsradikaler (radical right). I noticed this difference in political “turf” starkly over one particular night (and a long night it was). I, along with G.S., an American friend also studying in Germany at the time, walked clear across most of Berlin. It was ambitious, but we did it. (We started near Ostkreuz or Lichtenberg [which is definitely “deeply east”] at 10 PM or so, and ended west of the Westkreuz train station — on foot the whole way. It took us over eight hours. I don’t know whose idea this was, but it sounds like something I’d propose. We arrived past dawn at his apartment in the west [where I was staying for the time being while I sorted out a new place to live].)Anyway, about the Linke Party. I think we can say Linke is “two parties” that have joined together for convenience’s sake — one is a party for nostalgic ‘conservative’ east-Germans in or near retirement age (see above), and the other a party of and for the angrily radical left. Without the former, the party gets no voters and is stuck in the electoral ghetto (Linke has almost no representation anywhere in West Germany due to the 5%-threshold rule). Without the latter, the party lacks for energy, sags under the weight of political lethargy, and may not have survived to the present day.

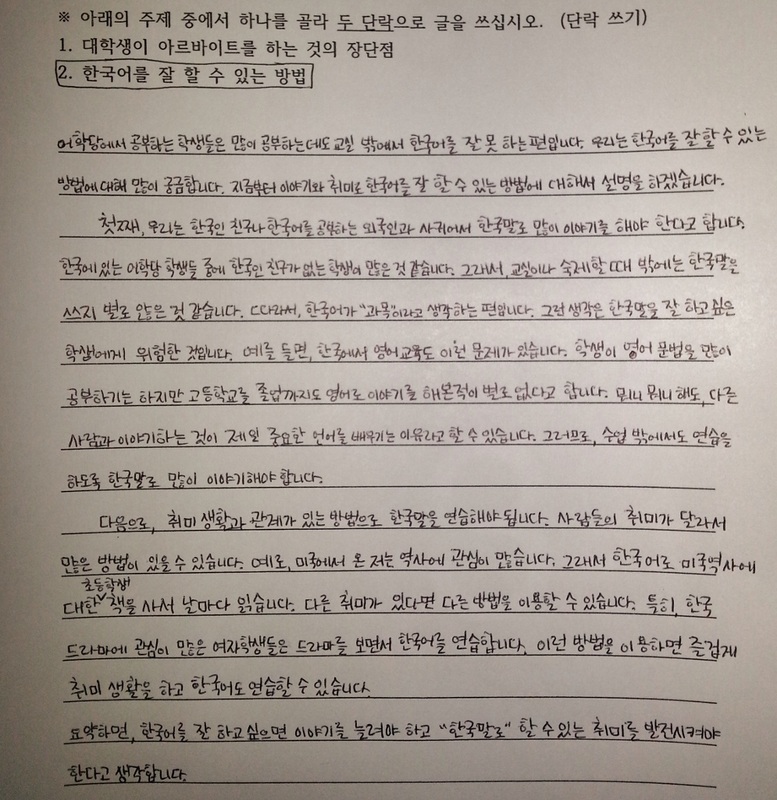

This was my opinion as an outside observer.bookmark_borderPost-247: [My Korean Essay] Methods for Speaking Korean Well

An English translation follows.

|

한국어를 잘 할 수 있는 방법

어학당에서 공부하는 학생들은 많이 공부하는데도 교실 밖에서 한국어를 잘 못 하는 편입니다. 우리는 한국어를 잘 할 수 있는 방법에 대해 많이 궁금합니다. 지금부터 이야기와 취미로 한국어를 잘 할 수 있는 방법에 대해서 설명을 하겠습니다. 첫째, 우리는 한국인 친구나 한국어를 공부하는 외국인과 사귀어서 한국말로 많이 이야디를 해야 한다고 합니다. 한국에 있는 어학당 학생들 중에 한국인 친구가 없는 학생이 많은 것 같습니다. 그래서, 교실이나 숙제를 할 때 밖에는 한국말을 별로 쓰지 않은 것 같습니다. 따라서, 한국어가 “과목”이라고 생각하는 편입니다. 그런 생각은 한국말을 잘 하고 싶은 학생에게 위험한 것입니다. 예를 들면, 한국에서 영어교육 도 이런 문제가 있습니다. 학생이 영어문법을 많이 공부하기는 하지만 고등학교를 졸업까지도 영어로 이야기를 해본적이 별로 없다고 합니다. 뭐니 뭐니 해도, 다른 사람과 이야기하는 것이 제일 중요한 언어를 배우기는 이유라고 할 수 있습니다. 그러므로, 수업 밖에서도 연습을 하도록 한국말로 많이 이야기해야 합니다. 다 음으 로, 취미 생활과 관계가 있는 방법으로 한국말을 연습해야 됩니다. 사람들이 취미가 달라서 많은 방법이 있을 수 있습니다. 예로, 미국에서 온 저는 역사에 관심이 많습니다. 그래서, 한국어로 미국역사에 대한 초등학생 책을 사서 날마다 읽습니다. 다른 취미가 있다면 다른 방법을 이용할 수 있습니다. 특히, 한국 드라마에 관심이 많은 여자학생들은 드라마를 보면서 한국어를 연습합니다. 이런 방법을 이용하면 즐겁게 취미 생활을 하고 한국어도 연습할 수 있습니다. 요약하면, 한국어를 잘 하고 싶으면 이야기른 늘녀야 하고 “한국말로 할 수 있는” 취미린 발전시켜야 한다고 생각합니다. |

Students of Korean, even those who study a lot, tend to be unable to speak very well outside of the classroom. We are very curious about ways we can speak Korean well. Here I will explain about how to improve in Korean with conversation and hobbies.

Firstly, we need to befriend Koreans or other students of the Korean language and speak with them in Korean a lot. Among students of Korean in Korea, it seems there are many who have no Korean friends. Therefore, outside of the classroom or time doing assignments, it seems they speak almost no Korean. Accordingly, there is a tendency to think of Korean as “a subject”. This kind of idea is dangerous for people who want to learn Korean. An example of the same kind of problem is in English education in Korea. Students study English grammar a lot, but even by the time they graduate from high school, they have almost never used English to speak to someone. When all is said and done, we can say that speaking to other people is the most important reason why we learn a language. This being the case, we need to be sure to practice outside the class by speaking in Korean a lot.

Additionally, we should use methods connected to our hobbies to practice Korean. Everybody has different hobbies, so many methods are possible. For instance, I am from the USA and I am interested in history, so I bought a Korean-language American history book for elementary school students and I read it every day. If a person has other hobbies, other methods are possible. Particularly, the female students who are highly interested in “Korean dramas” [Korean TV soap operas popular in East Asia in the 2000s and 2010s] can practice Korean while watching them. Using this kind of method, we can enjoy our hobbies and also practice Korean.

In summary, those who want to speak Korean well should increase the amount they speak in Korean and also develop “hobbies that can be done in Korean”.

bookmark_borderPost-246: Here Comes Bodo Ramelow (Or, Reminiscences of German Politics)

The state will be Thuringia (Thüringen), formerly belonging to East Germany.

The leader will be somebody called Bodo Ramelow (born 1956).

Here he is:Or, maybe you’re thinking “Bodo Ramelow sounds like a pro wrestler’s name.”

I agree with both sentiments.

Bodo will take the helm as “Minister President” of Thuriginia following that state’s election in fall 2014. Here are the results, with my attempt to transliterate onto U.S. politics:

- [91 seats allocated, based on a mixed system of proportional voting and U.S.-style “most votes wins” contests:]

- 34 won by the CDU (Christian Democratic Party, akin to moderate U.S. Republicans) [37% of seats]

- 28 won by Die Linke (successor of the East German Communist Party) [31% of seats]

-

12 won by the SPD (Social Democrats, akin to the left-wing of the U.S. Democrats) [13%]

- 11 won the AfD (a new party, “Alternative for Germany”, similar to the U.S. Tea Party circa 2010) [12%]

- 6 won by the Green Party [7%]

- 0 seats were won by the Free Democratic Party (akin to the free-market wing of the Republican Party)

- 9.7% of voters voted for parties that won no seats (including the FDP) due to the “5%-threshold rule”. (Most of the usual FDP voters voted for the new AfD party this time.)

A coalition government is to be formed unless one party gets a majority, and that never happens in Germany. Any group of parties, if their combined seats constitute a majority of the legislature, can form a government. If you count these up, you’ll see that the Linke [31% of seats] and SPD [13%] and Greens [7%] have a 51% majority, so they can exclude the CDU and AfD. The thing is, the Linke “neo-Communists” are a majority of this ruling coalition, so it’s only fair that their guy, Bodo, becomes the formal leader.

Communists and Anti-Communists in Berlin

I was in Berlin, Germany for most of 2007. I remember noticing how much the continued presence within German politics of the “neo-Communist” (die Linke) annoyed certain factions in Germany. The party’s remains strong in the east, where older people’s votes keep it a significant force.

This all reminds me of the high energy of street politics in Germany. Radicals were kinetically active in a way I never saw in the U.S. or anywhere else. Stickers, leaflets, posters, and graffiti were everywhere. It meant that people took this stuff seriously. A lot of it was clever. “Political subculture people” were also easy to spot by their manners of dress, manners of carrying themselves, places they’d hang around, and even haircuts.

I still have, somewhere, a booklet-manifesto somebody who called himself a professor handed me. It was in German, and expounded his theories on why we need Marxism now more than ever, from what I could gather. He was standing on a street corner but as street-corner people go, he seemed normal. We talked a short while. He realized after a short exchange that I was not a German native speaker. I lied and told him I was from Denmark, which he seemed to accept. I ended up walking away with not only his cream-colored booklet containing his Marxist manifesto, but also an equal-sized cream-colored booklet on Buddhism. I think he’d written both. I think his name was something like Rolf.

Anyway, this stuff made life interesting.

I made a habit of studying any political graffiti or suchlike that I found in Berlin. I recall one leaflet, produced I expect by right-wing radicals, that said something very close to “Zwei Jahrzehnte Nach Mauerfall, Kommunisten noch überall!” (“Two decades after the fall of the wall, Communists still rule us!”). This cleverly rhymes in German. It was in reference to the fact that the “neo-Communist” Party (to which the above-pictured Bodo Ramelow belongs) was then in coalition with the SPD ruling Berlin. Accompanied was a cartoon picture of a man smashing a red star with a sledgehammer. This kind of thing was a common sight in Berlin, though far-left material of the same kind was more common to see.

Update, 11/22: Another part of this above-mentioned anti-communist leaflet comes back to me. In smaller letters, it urged the reader as follows: “Politischer Kampf den Roten Banden” ([Let’s wage] a political struggle against the red thugs). It then identified several communist groups by name (including the political party now called “die Linke”) around the red-star being smashed by the heroic-looking cartoon man.

.

bookmark_borderPost-245: On the Fall of the Berlin Wall

I think historians of the future ought to use the two (11-11-1918 to circa 11-11-1989) as bookends, to fence off a coherent era of history. It is convenient, or poetic, or something special anyway, that the period is exactly seventy-one years to the day. Those seventy-one years were an era of wild political-ideological struggle, unseen, really, before or since.

- November 11th, 1918 : WWI ends as the armistice goes into effect at 11 AM. That war really brought down the old aristocratic order in Europe. As a result, politics was “opened up” very widely, perhaps more widely than it has ever been, before or since. Formerly-fringe “radicals” proliferated everywhere.

- 1918 through the 1960s: A lot of stuff happens, in a lot of directions. As the smoke clears, Soviet-model Communism is arguably the biggest winner of the decades of political struggle after 1918. Certainly the biggest if looked at in relative terms; from zero communist states on the map in 1917 to something like half the world in the 1960s.

- November 9th and 10th, 1989: The Berlin Wall Falls. The East German Communist government allows free border crossing and anti-communist radicals quickly take to smashing up the wall. The same was happening everywhere across the Soviet bloc in these months, but the symbolism too profound to not focus on Berlin. Breached late in the day on the 9th, free movement persisted on the 10th. As the sun rose on November 11th, still no crackdown. It must’ve been clear to everyone by, say, lunchtime (11 AM?) on the 11th that “Soviet-model Communism” was finished as an ideology and force in the world. The East German Communist state had gone out with a whimper. (The ex-Soviet bloc faced dreary years ahead. Ukraine: In 2013 [before the coup and ongoing civil war] Ukraine’s economy was, incredibly, still only two-thirds its 1989 size. See post-194).

November 11th, 1918 to November 11th, 1989: The Era of Ideological Struggle.

I don’t remember any of it.

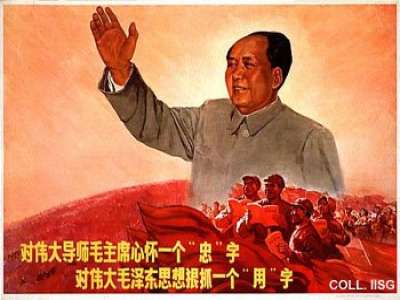

bookmark_borderPost-244: Mao Zedong the Praiseworthy

|

Suh Teacher was discussing a particular Korean word, “훌륭하다”. This word means “excellent; stately; honorable; respectable; commendable; admirable; praiseworthy.” Listening were the students of our class, 15 in all — thirteen from China, one Chinese-Malaysian, and me. To make sure students understood how to use the word, Suh Teacher asked, “Okay, then, for whom can we use this word? Examples?” It was an open question to the room.

|

|

Very quickly came a girl’s exclamation: “Mao Zedong!” (something like “Mao Dzhuh-doong” in Korean, which follows Chinese pronunciation, I suppose). The class did what it often does, which is to laugh in unison. (When these spontaneous eruptions happen, it always seems as if they’d been planned. It hadn’t been “planned”; there is just a Chinese Consensus in the room.) (The concept of “Chinese Consensus” has occurred to me before in classes, so I’ll capitalize it here so as to dignify it with an implied existence.)

I wondered why they were laughing. |

|

My impression, from the many Chinese whom I’ve met while studying Korean, is that they really do like that man. At the same time, maybe most are aware enough to know that Chairman Mao, revered back in China down to the present day as he may be, is something of an enemy figure to South Koreans, certainly to older ones. He sent a million men to try to quash the existence of the Republic of Korea in 1950, after all. Hence the awkward laugh. This is my best explanation.

As the Chinese Consensus’ laugh was ebbing past its peak, something completely unexpected happened. My favorite of the thirteen Chinese, J.G., a male about 20 years old, a voracious coffee drinker and always in good humor, exclaimed “아니요!” (“No!”). It was the first thing anyone had said since Mao was suggested as an “admirable, praiseworthy” figure a moment earlier. J.G. was animated. Along with his “No!”, he did some kind of motion akin to humorously slamming the desk. It’s not clear to me to what extent he was joking. But he then — and this really was shocking to me — apparently suggested an alternative “admirable figure” in the person of Chiang Kai-Shek, the founder of Taiwan, arch anti-Communist, arch-enemy of Mao Zedong. The teacher asked if this is who he’d meant. “대만을 만든 사람?” (“The person who ‘made’ Taiwan?”). “Yes”, J.G. said. There was no counter-reaction. The Consensus disintegrated into disorganized giggles and confusion. The teacher moved on. |

bookmark_borderPost-243: “The Great Pumpkin Will Appear!”

Linus evangelizes on behalf of the Great Pumpkin, a supernatural being he believes in. He is convinced that the Great Pumpkin will appear on Halloween Night in the pumpkin patch, and plans an all-night vigil. He tries to get others to join him. No one is convinced. Charlie Brown’s little sister Sally finally gets involved, but she is completely uninterested in the metaphysics of the Great Pumpkin. Rather, she wants to spend time alone with Linus, whom she likes. The attraction is not reciprocal, but Linus gladly takes her on as another disciple of the Great Pumpkin.

At one point, Schulz has Linus write a letter to the Great Pumpkin saying:“Everyone tells me you are a fake, but I believe in you. P.S., If you really are fake, don’t tell me. I don’t want to know.”

Night comes; the Great Pumpkin doesn’t show up; Sally gets annoyed and storms off; Linus stays loyal and remains at his post. The next thing we know it’s 4 AM, and — shivering and having fallen asleep still at his vigil post — Linus is dragged inside and put to bed.

On the morning of November 1st, the show ends with this exchange:

Charlie Brown: [Dejectedly] Well, another Halloween has come and gone.

Linus: [More Dejectedly] Yes, Charlie Brown.

Charlie Brown: I don’t understand it. I went trick-or-treating and all I got was a bag full of rocks. I suppose you spent all night in the pumpkin patch.

Linus: [Nods]

Charlie Brown: And the Great Pumpkin never showed up?

Linus: Nope.

Charlie Brown: Well, don’t take it too hard, Linus. I’ve done many stupid things in my life, too.

Linus: [Shocked] [Turns angry] “Stupid”? What do you mean, “stupid”? [Flails arms in frustrated anger] Just wait till next year, Charlie Brown! You’ll see. Next year at this same time, I’ll find a pumpkin patch that’s real sincere. I’ll sit in that pumpkin patch until the Great Pumpkin appears. [Finger in the air, as pontificating] He’ll rise out of that pumpkin patch and fly through the air with bags of toys. The Great Pumpkin will appear! I’ll be waiting for him. I’ll be sitting there in that pumpkin patch and I’ll see the Great Pumpkin. Wait and see, Charlie Brown! I’ll see the Great Pumpkin! [End of Show]

At the same time, Linus is a sympathetic character throughout (despite his show-ending diatribe). Watching the show, we want the Great Pumpkin to be real. Linus as a tragic hero. When Snoopy pops up in the shadows, for a split second, we, along with Linus and Sally looking on, want to believe it is the Great Pumpkin itself.

And alas, was Linus’ Halloween (an all-night vigil) really any worse spent than Charlie Brown’s own, who tried to have his fun but ended up with a bag full of rocks?

bookmark_borderPost-242: November 11th, 1918

One of my great-grandfathers was in the U.S. Army at that time, but he never left the USA. I wrote about what I’ve learned of his experience in post-224 (“My Great-Grandfather’s Piece of World War I“). He was at Camp Devens, MA. Here is a picture of one of the companies garrisoned (not his) at Camp Devens in 1918:

Within two years of the armistice, Earle Hazen was married and within three years, my grandmother was born.