The memories are vivid, even as I sit here in the spring of 2013, four years later.

Part I: “A Pig Virus Delays My Arrival“

and

Part II: “Into the Wild Neon Yonder”

[Simple synopsis of Part II: From the airport to my new workplace]

The elevator door opens. The inside of the institute is bright and clean, impressive. Two hallways lead off towards classrooms on either side of the front-desk. The first person I see is seated behind that front-desk, a receptionist-secretary (or “Desk Teacher”, as they were called). In the seven or eight months she and I worked together, she was to say a total of two words to me: “Hi” was one. The other was “Bye”. She was shy, and she didn’t know much English, but she was pleasant. From what I saw, she had that kind of “hardline” shyness that if observed in a child in the USA would alarm people but in Korea is generally not considered problematic.

It is around 11 PM. The timing worked out well: The language-institute’s schedule was for teachers to be there from 3 PM to 11 PM. Classes were held between 4:30 PM and 10:30 PM. This meant my arrival was after the students had left, but while the teachers were still there. I was a bit self-conscious about showing up with suitcases in hand in front of soon-to-be coworkers, but at least it wasn’t in front of dozens of soon-to-be students.

Soon, a Korean woman of about 40, with short hair and an amiably-forceful personality, materializes and greets us. This is Mrs. Y, the boss. She is smiling broadly. I did not, at that moment, know who she was: I didn’t know much of anything about anything then. In March of 2009, while in the USA, I’d talked to her husband on the phone. He ran, and as of this writing still runs, the other campus of this language-institute. This was no corporate-owned franchise, but a mom-and-pop operation (quite literally: They have a daughter, whom I taught). Anyway, the husband had interviewed me. He was a smooth interviewer. The contract I subsequently signed bore his name, I think. My visa didn’t say his name, but rather Mrs. Y’s, although I couldn’t read the Korean yet, so I was ignorant of that fact.

Yes, Mrs. Y would be my boss for the next twelve months, and a very engaged boss she was. Some bosses are resented because — it seems to their subordinates — they coast off the work of others, and don’t seem to really do anything. This is certainly my feeling about the top-tier of managers at my current job (as of spring 2013), but was not the case at all with Mrs. Y: She definitely worked more than the rest of us. Besides being (as co-owner) in charge of the money and the administrative and marketing sides of running the business, she was a full-time teacher. It was like she did two full-time jobs. The problem was, she expected everyone to be as committed as she was.

She took on a full-load of classes because she loved teaching, I think, more than it being about only saving money.

A 1978 photograph of Gangnam’s

A 1978 photograph of Gangnam’s

Apgujeong neighborhood / (From here)

I think this is worth telling. As I was able to piece it together, this is Mrs. Y’s history:

Mrs. Y, was born somewhere in the southern part of the country in the spring of 1970. I believe it was Gyeongsang Province. The average Korean woman in those days bore 4.5 babies, and the country was poor, arguably worse-off than North Korea: I’ve read that South-Korea was poorer than North Korea from 1945 until as late as 1970. In 1970, a former army-general was president(-for-life) of South Korea after having taken power in a coup nine years earlier, and political dissidents regularly “disappeared”. The sites of the new developments in and around Seoul — such as Ilsan (where this woman now stood before me) and now-famous Gangnam — existed as farmland, as in the photo above.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the South-Korea into which Mrs. Y was born resembled the North Korea of today more than it resembled the South Korea of today! That fact explains a lot about her personality, and the personality of her generation, I think.

By the time Mrs. Y entered high school, South Korea’s fertility rate had dropped to 1.5 babies/woman, and military rule was relaxing, though a general was still president.

Mrs. Y told me that, as a girl in the early 1980s, she developed a strong interest in American pop music. She said music was what drove her to major in English at university. Although she did also express to me ambivalent feelings about the USA itself (a typical South-Korean attitude), I don’t doubt that she felt attracted to American pop music, about which she seemed very well-informed.

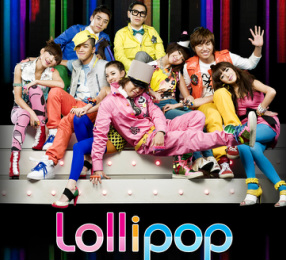

A publicity poster for a song by two major

A publicity poster for a song by two major K-Pop groups, “Big Bang” and “2NE1”, 2009. /

My boss told me she was drawn to American

pop music in the 1980s, before K-Pop existed.

Most early-2010s Korean middle school students, with whom I have interacted at my jobs, have seemed under the impression that K-Pop singers are among the most famous in the world. I have never had the heart to tell them that K-Pop has been (generally) totally unknown in the USA, until the novelty song by Psy last year.

Mrs. Y majored in English in university in the early 1990s.

Perhaps if K-Pop had existed in the 1980s, she never would never have studied English at all. It’s possible.

By the mid-1990s, it seems she was teaching in English language-institutes. She met her husband (a former KATUSA with an MBA from a U.S. university) around 1996. They got married and their daughter was born in 1997, I think. I taught the daughter when she was in 6th and 7th grades. By year 2000 (at latest), the family was in Ilsan. They both earned good money in the then-booming language-institute business, and in the mid-2000s they opened their own place. In mid-2008, Mrs. Y opened her own campus in southern Ilsan. It was this place that would be my home for the next year, six days a week.

Her English was excellent, I would say totally fluent, except for an occasional “how could she have known” mistake, like saying “MVP” instead of “MVP” (emphasis on ‘P’). I am very impressed that someone could develop such a mastery without ever having gone abroad.

Mrs. Y was being very positive and energetic that night, and trying her best to be pleasant. She ushered me into her office and offered me some of the milkiest and sweetest coffee I’d ever tasted. She spent a couple of minutes talking and showing me my schedule. The schedule was full to the brim with classes.

Her veneer of enthusiasm showed small cracks while in her office for those few minutes. I was reminded of that old adage about bears being more afraid of you than you are of them. Maybe it was because she saw in me someone utterly clueless about the ways of Korea, and was having second-thoughts about hiring me. More likely, she was embarrassed that I had the most classes of any teacher, and that I would be working on every Saturday (as we all were). I told myself I’d be okay with it. In fact, though Saturday (half-day) work in particular sounds bad, and does limit time for leisure and trips, I really liked it. Saturday work was definitely the most relaxed and “fun” day of all.

Our brief orientation was over. She said we needed to go down and join the others at a nearby restaurant, where they had already begun eating. We put my suitcases in the trunk of her car and got in. . . .