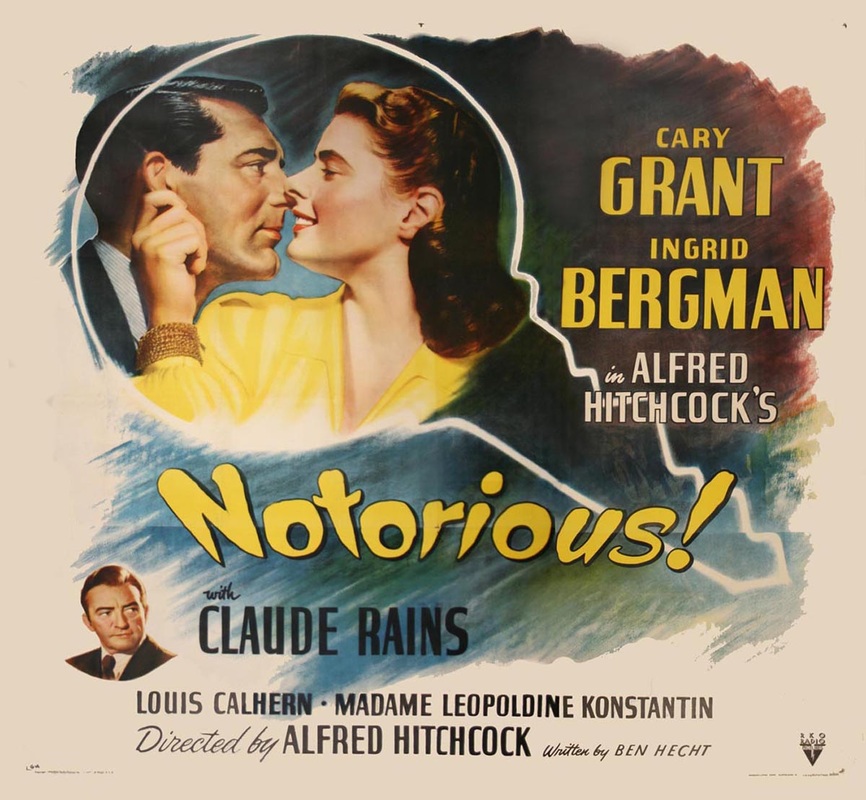

The movie is actually a romance story between the lead American agent (Cary Grant) on the case and the German-American young woman (Ingrid Bergman) whom the FBI asks to infiltrate the safehouse.

A series of events leads the Claude Rains character, the head of the safehouse, to realize that his new wife is an American agent, and he panics. If he admits the fact that he has married an American agent to the other safehouse people, he fears they will kill him. His mother, who is also a resident of the safehouse, persuades him to poison her, and he reluctantly agrees. Sure enough, she is rescued at the last minute by Cary Grant.

For one thing it is an early example of James Bond. Cary Grant plays James Bond here, many years before James Bond was created. This is a genre that audiences became familiar with as the 20th century rolled on.

A very similar movie could be made today, with one glaring exception (as I see it):

The “Nazis” in this movie (filmed in late 1945 and early 1946), with one or two exceptions among certain lesser characters in the safehouse, are more sympathetic than Nazis whom we would see on screen in a film produced today. This is amazing given that the war had only been over for six months at the time of filming. Certainly the main German exile character (played by Claude Rains) is a sympathetic character. We are shown a human rather than a “Nazi”; a tragic figure with his own struggles in life just like anyone else.

Do I mean to say that Hitchcock was a “fascist sympathizer” himself? Surely not. I think something much more interesting may be going on here: I am reminded again of the newspaper columns by George Orwell in 1945 and 1946 and thereabouts (see also #59), reporting from a ruined Germany. He reported that the Germans were so thoroughly defeated that any more anger at them just seemed superfluously cruel; sadistic. He reported one scene he witnessed in which, months after the surrender, a guard kicked, spat on, and otherwise abused a shackled German SS man, a POW. Orwell pointed to how senseless this seemed. The war is over; their side is totally defeated; what are you doing? Let’s extinguish the flames of war passion and try instead to kindle (rather than strangle the life out of) the long-suppressed spirit of Good Will Toward Men now trying to crawl up out of the ashes, Orwell seemed to say in many of those columns/essays from those years. Maybe Hitchcock, directing “Notorious” about the same time, had a similar idea in mind. In the immediate period after Germany’s surrender, portraying the Germans as unequivocally evil would seem just plain lazy, if nothing else, and Hitchcock could never be lazy.

As it turns out, of course, in recent decades ever-more-histrionic portrayals of Nazis have prevailed in Hollywood. This means that, ironically, movies made in the 2000s and 2010s, sixty and seventy years after the fact, are much more “anti-Nazi” than this movie, “Notorious”, filming of which began six months after the end of the war!