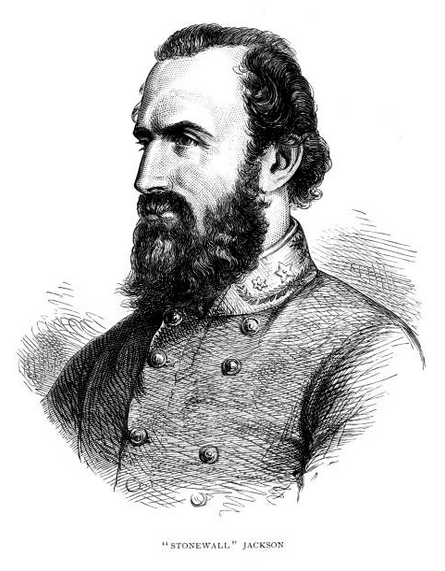

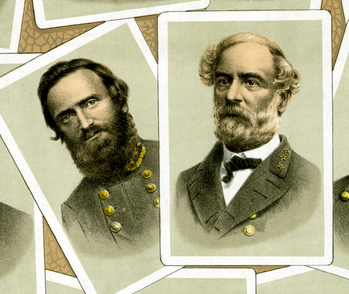

Lee–Jackson Day in Virginia.

No doubt many are unaware of the Lee–Jackson Day holiday. The two sons of Virginia, Robert E. Lee and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, have birthdays about this time (Jan. 19 and Jan. 21, respectively), a coincidence which gave rise, a long time ago, to the holiday in Virginia. It remains in effect today, even if backed by no enormous media machine.

As for Stonewall Jackson, I can think of no better way to commemorate him than Stonewall Jackson’s Way, which is a song (below), but more a musical portrait.

It is a great piece of art in that it is an effective portrait of the general, his men, and the campaigning that brought fame and renown to both.

The song “Stonewall Jackson’s Way” was originally written in 1862 and appearing in poem form but also quickly becoming a hit song. The song’s composer was unknown for years. Testament to how alluring was the legend of Stonewall Jackson, by 1862, is the fact that an northern admirer had actually written the poem/song, a fact only finally revealed in the 1880s.

The version recorded by Bobby Horton in the 1980s is good (below); Horton rightly deserves his fame as a Civil War music interpreter/popularizer.

“Stonewall Jackson’s Way” Lyrics, as sung by Bobby Horton (below, a few more comments below on the figure of Jackson, and on my feelings on Lee–Jackson Day):

Come, stack arms, men! Pile on the rails,

Stir up the camp-fire bright;

No matter if the canteen fails,

We’ll make a roaring night!

Here Shenandoah crawls along,

Here burly Blue Ridge echoes strong,

To swell the brigade’s rousing song

Of Stonewall Jackson’s Way!

We see him now,

The old slouched hat,

Cast o’er his eye askew;

The shrewd, dry smile,

The speech so pat,

So calm, so blunt, so true.

That “Blue Light Elder,” knows him well.

Says he, “That’s Banks, He’s fond of shell;

Lord, save his soul! We’ll give him — well!”

That’s Stonewall Jackson’s way.

Silence, ground arms, kneel all, caps off!

Old “Blue Light’s” gonna pray.

Strangle the fool that dares to scoff!

Attention! That’s his way.

Appealing from his native sod,

“Hear us, hear us, Almighty God!

Lay bare Thine arm; Stretch forth thy rod,”

That’s Stonewall Jackson’s way!

He’s in the saddle now, Fall in!

Steady the whole brigade;

Hill’s at the ford, cut off, we’ll win

His way out, ball and blade!

What matter if our shoes are worn?

What matter if our feet are torn?

Quick-step! We’re with him ere the dawn!

That’s Stonewall Jackson’s way.

The Sun’s bright lances rout the mists,

Of morning, and by George!

Here’s Longstreet, struggling in the lists,

Hemmed in an ugly gorge.

Pope and his Yankees, went before,

“Bayonets and grape!” hear Stonewall roar;

“Charge, Stuart! Pay off Ashby’s score!”

In Stonewall Jackson’s way.

Ah! Maiden, wait and watch and yearn

For news of Stonewall’s band!

Ah! Widow, read, with eyes that burn,

That ring upon thy hand;

Ah! Wife, sew on, hope on, and pray,

That life shall not be all forlorn;

The foe had better ne’er been born

That gets in Stonewall’s way!

________________

Despite being a Virginian, technically, by birth and upbringing, I am not a real Virginian. I have no roots in the US South at all.

From about ages 13 to 16, I recall being against figures like Lee and Jackson, a safe and rather predictable position for someone growing up where I was (Arlington, Va.). Despite knowing very little about them, I was sure they were bad, “because reasons.” In the tear-down-the-statues crowd of recent years, I recognize a past self, a self I gladly left behind many years ago.

Jackson and Lee both get sympathetic treatment in the bestselling Gods and Generals (a novel-like narrative of the Civil War from 1859 to May 1863), the prequel to Michael Shaara’s mega-bestseller Killer Angels (the novel-like narrative depiction of the Gettysburg campaign, June and July 1863). Gods and Generals‘ narrative follows four personalities, in alternating chapters: Lee, Jackson, Hancock, and Chamberlain (the latter being the hero of Killer Angels; the influence of that book [1974; Pulitzer Prize] and movie [1993] on the narrative around Gettysburg, with Col. Chamberlain and the 20th Maine at Little Round Top, has deeply influenced our popular understanding of that war today; people don’t like to hear that the war was not won at Little Round Top and that Gettysburg despite its grand scale was strategically inconsequential; the decisive campaign of the war was Sherman in Georgia in 1864).

They were rather different sorts of men, but both representing an archetype of classic Virginia: Jackson, from the hills of western Virginia, was an austere Presbyterian of the old sort (captured in the song “Stonewall Jackson’s Way”); Lee, an eastern aristocrat-gentleman, Episcopalian, a man who has always been seen as a kind of symbol of the best of old Virginia. With their talent as commanders, few have dared argue.

Lee was also a lifelong resident of the Virginia side of the Potomac around today’s Alexandria and Arlington, Va., and had ties to the George Washington family. When Arlington organized its first public high school, they called it Washington-Lee in honor of the two local men, a topic I plan to write more about soon given recent developments and my connections to them. (As it happens, there was also once a Stonewall Jackson Elementary School in Arlington, the name of which was quietly killed in the late 1990s.)

Lee and Jackson, each in his own way, had that rare ability to motivate men to greater deeds than the men should have been able to do, on paper. And consistently. On the question of how he kept winning battles, often lopsidedly, Jackson once said to his interlocutor, while overlooking his men marching past, fresh off the latest victory:

“Who could not conquer with such troops as these?”

Such was Jackson.

The song doesn’t quite define what “Stonewall Jackson’s Way” was, in any firm sense. The qualities that have inspired the hearts of men down through all history would seem to be it.

In the book I read earlier this month on the Thirty Years War, a comparable portrait emerges of the Swedish king and field marshal Gustavus Adolphus, the most charismatic figure of the war.

Jackson was much less naturally charismatic a figure as Gustavus was 230 years earlier, but his religious devoutness and general taciturnity became a part of his allure.

We see him now,

The old slouched hat,

Cast o’er his eye askew;

The shrewd, dry smile,

The speech so pat,

So calm, so blunt, so true.