Gettysburg Art, by Don Troiani

Gettysburg Art, by Don Troiani

This goes against what we’ve been told in movies. Gettysburg was the turning point, we are told. The strategic situation in the East was exactly the same in Fall 1863 (after Gettysburg) as it had been in Spring 1863 (before Gettysburg). Nothing changed. It was, by definition, not a turning point, because nothing changed. I remember thinking, “Okay, but Gettysburg must have increased Union Army morale”. It was the first time the Army of the Potomac (the eastern Union army) actually decisively won a major battle. It was the first time the Army of the Potomac did not retreat after a battle. That must count for something.

Chipyong-ni Artwork

Chipyong-ni Artwork

See the long essay from the U.S. Center for Military History entitled “Restoring the Balance: 25 January to 8 July 1951” for a full history of the campaign.

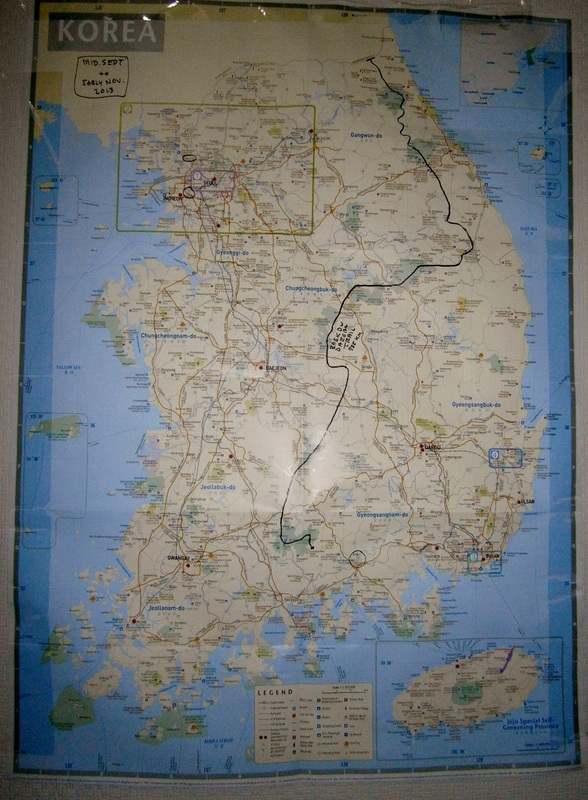

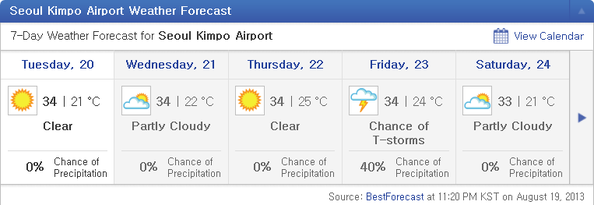

In the two weeks before the February 13th-15th battle, the UN had taken a limited offensive, as below. The dark line was the frontline as of January 25th, and the dotted line was the front as of February 11th. Note that Chipyong-ni was the point of furthest advance in the area.

[From “Restoring the Balance”]

While UN forces in Operation THUNDERBOLT advanced to an area just south of the Han against only minor resistance, Chinese and North Korean forces were massing in the central sector north of Hoengsong seeking to renew their offensive south. On the night of 11-12 February the enemy struck with five Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) armies and two North Korean corps, totaling approximately 135,000 soldiers. The main effort was against X Corps’ ROK divisions north of Hoengsong. The Chinese attack, dramatically announced with bugle calls and drum beating, penetrated the ROK line and forced the South Koreans into a ragged withdrawal to the southeast via snow-covered passes in the rugged mountains. The ROK units, particularly the 8th Division, were badly battered in the process, creating large holes in the UN defenses. Accordingly, UN forces were soon in a general withdrawal to the south in the central section, giving up most of the terrain recently regained. Despite an attempt to form a solid defensive line, Hoengsong itself was abandoned on 13 February.

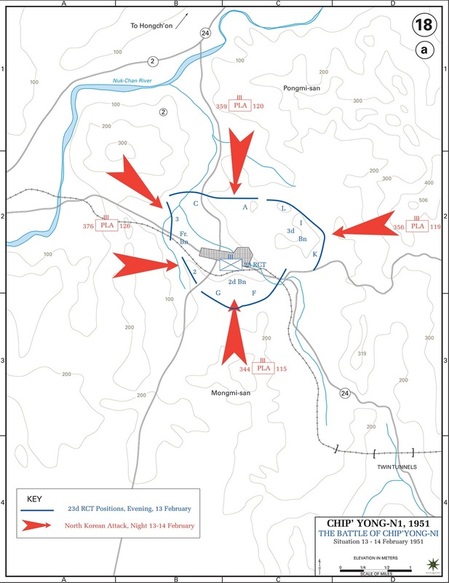

Also on the thirteenth the Chinese broadened the offensive against the X Corps with attacks against U.S. 2d Infantry Division positions near Chip’yong-ni, on the left of the corps’ front. They also struck farther to the west out of a bridgehead south of the Han near Yangp’yong against elements of the U.S. 24th Infantry Division, holding the IX Corps’ right flank. The 21st Infantry of the 24th Division quickly contained the Yangp’yong attack that was aimed toward Suwon, but at Chip’yong-ni the Chinese encircled the 2d Division’s 23d Infantry and its attached French Army battalion, cleverly exploiting a gap in the overextended American lines.

Chip’yong-ni was a key road junction surrounded by a ring of small hills. Rather than have the 23d Infantry withdraw, General Ridgway directed that the position be held to block or delay Chinese access to the nearby Han River Valley. An enemy advance down the east bank of the Han would threaten the positions of the IX and I Corps west of the river. Accordingly, the UN forces at Chip’yong-ni dug into the surrounding hills and formed a solid perimeter while reinforcements were mustered. The role of the Air Force was essential at Chip’yong-ni with close air support forcing the attackers to conduct their assaults only after dark. And once the enemy had cut off the ground routes, all resupply was by air.

As Ridgway hoped, the 5,000 defenders of Chip’yong-ni quickly became the focus of Chinese attention. Throughout the night of 13-14 February, three Chinese divisions assaulted the perimeter, supported by artillery. The attackers shifted to different sections of the two-mile American perimeter probing for weak points. The Chinese were often stopped only at the barbed wire protecting the individual American positions, with the defenders employing extensive artillery support and automatic weapons fire from an attached antiaircraft artillery battalion. Daylight brought a respite to the attacks. True to form, the Chinese renewed their assaults the night of 14-15 February. Again the fighting was intense. During the 14 February attack, Sfc. William Sitman, a machine gun section leader in Company M, 23d Infantry, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in providing support to an infantry company, in the end placing his body between an enemy grenade and five fellow soldiers.

While the 23d Infantry held on at Chip’yong-ni, the situation to the southeast was grave. At the time Ridgway and Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, the X Corps commander, were seeking to stabilize the front line between Chip’yong-ni and Wonju, where the destruction of the ROK forces around Hoengsong had created major gaps in the defensive line. For three desperate days, the front wavered as the Chinese attempted to exploit these gaps before UN reinforcements could arrive on the scene. Ridgway acted quickly to push units into the critical areas, ordering IX Corps to move the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade and the ROK 6th Division over to X Corps and into the gap south of Chip’yong-ni. The action proved timely. On the night of 13-14 February, the Chinese conducted major assaults at Chip’yong-ni, Ch’uam-ni, five miles southeast of Chip’yong-ni, and at Wonju. But supported by massed artillery and air support, the UN forces repulsed the attacks, causing heavy Chinese casualties.

To provide additional support, the IX Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Bryant E. Moore, now began directly assisting the X Corps in restoring the front and relieving Chip’yong-ni. On 14 February the 5th Cavalry, detached from the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division, was taken out of IX Corps reserve and assigned the relief mission. For the task, the three infantry battalions of the 5th Cavalry were reinforced with two field artillery battalions, two tank companies, and a company each of combat engineers and medics. Initially the relief force advanced rapidly, making half the twelve-mile distance to Chip’yong-ni from the main U.S. defensive line on the first day. Damaged bridges and roadblocks then slowed movement. On the morning of the fifteenth, two of the infantry battalions assaulted enemy positions on the high ground north of the secondary road leading to Chip’yong-ni. When the attack stalled against firm Chinese resistance, Col. Marcel Crombez, 5th Cavalry commander, organized a force of twenty-three tanks, with infantry and engineers riding on them, to cut through the final six miles to the 23d Infantry. The tank-infantry force advanced in the late afternoon, using mobility and firepower to run a gauntlet of enemy defenses. Poor coordination between the tanks and supporting artillery made progress slow. Nevertheless, in an hour and fifteen minutes the task force reached the encircled garrison and spent the night there. At daylight the tanks returned to the main body of the relief force unopposed and came back to Chip’yong-ni spearheading a supply column. With the defenders resupplied and linked up with friendly forces, the siege could be considered over. UN casualties totaled 404, including 52 soldiers killed. Chinese losses were far greater. Captured documents later revealed that the enemy suffered at least 5,000 casualties. The defense of Chip’yong-ni was a major factor in the successful blunting of the Chinese counteroffensive in February 1951 and a major boost to UN morale. [From “Restoring the Balance“]

Far off to the east of Chipyong-ni, Seoul itself was still in Chinese hands at the time of the battle (Feb. 1951), and would be till mid-March. It was nearly recaptured yet again by the Chinese in April/May 1951. “Chinese hands”. That’s the other interesting thing about Chipyong-ni. It was a major battle of the Korean War, but very few Koreans were actually involved. According to the elderly museum-keeper at Chipyong-ni, only 150 Koreans were part of the U.S. force at Chipyong-ni and they were KATUSAs (English-speaking Koreans to facilitate communication).

I visited the site of the Battle of Chipyongni in September 2013. In 2012, after reading The Longest Winter, I identified the location of the battle by figuring out its current name. What we wrote in English in the 1950s as “Chipyong” is now written as “Jipyeong” [Gee-pyuhng] (지평리 in Korean). Its suffix, ri or ni, means “village” in Korean. It has since been promoted to “myeon”, a slightly larger settlement than a ri/ni. The current name is thus Jipyeong-myeon (지평면).

I will write about the visit later. For now I can say it was one of the most significant excursions of my time in Korea. I feel blessed that it worked out the way it did. The word “Chipyongni” does not even appear in the tourist guidebook I have. It was something I independently discovered.