“Philistine” was German student slang of the 1700s. It was used by Goethe in the modern-English sense in the late 1700s. It didn’t enter English until Matthew Arnold popularized it in the 1860s.

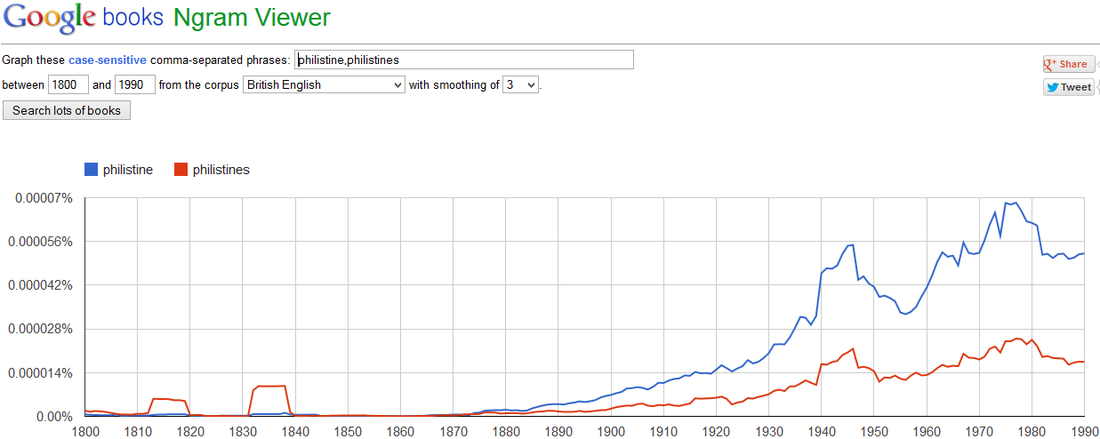

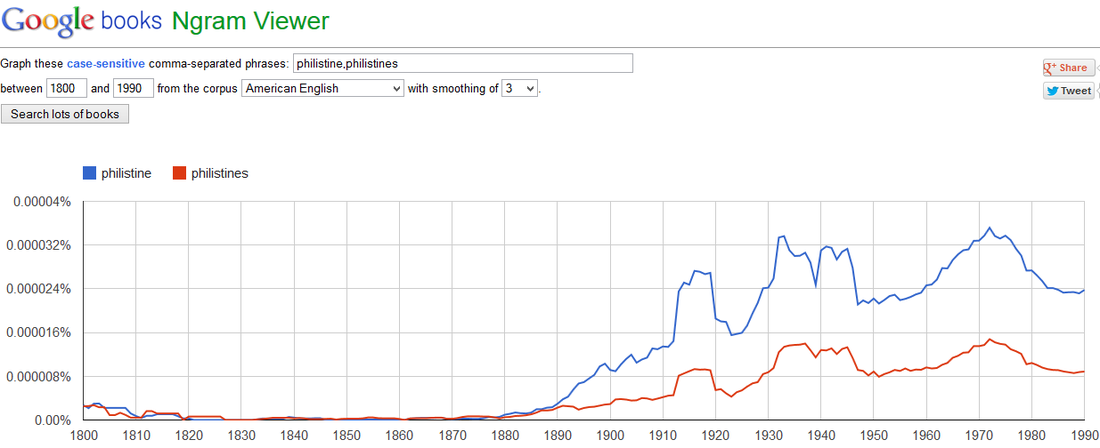

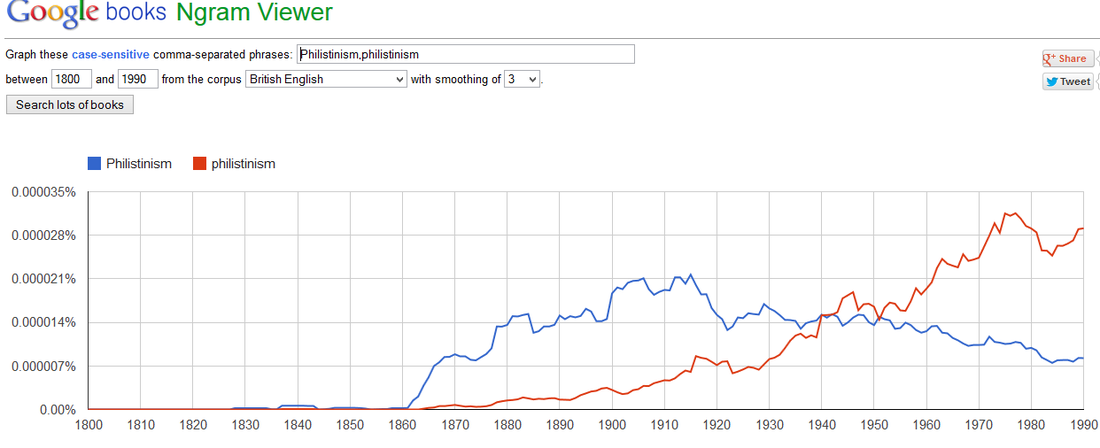

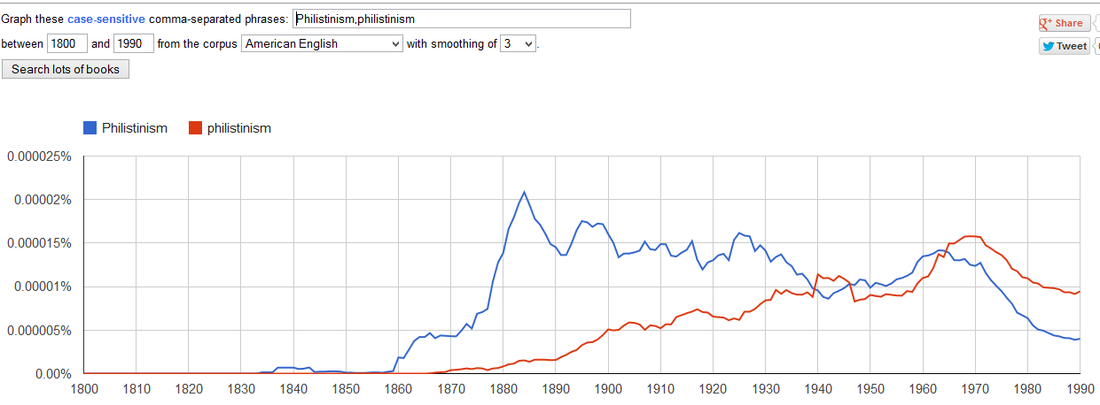

Here are the occurrences of the word, from 1800-to-Present in the corpus of Google-Books. First, “British English” (books published in Britain) and next “American English” (books published in the USA).

(1) These graphs are not the same scale. I don’t think there is a way to manipulate that.

(2) The smoothing is 3 [base-year + three years before and after, i.e. “1880” in the above is actually 1887-1893, averaged).

(3) Google-ngram is capitalization-sensitive. The word “philistine” yields totally different results from “Philistine”. Bibles or other references to the Biblical ethnic group would all be capitalized. Uncapitalized uses, then, mean “uncultured”. However, some early uses may actually have been capitalized, before it became fully-entered English as a lowercase derogatory term for an uncultured person.

Is “Philistine” a British or an American Word?

The term was popularized in English via the efforts of Matthew Arnold, so its origin in English is British. It became more American over time, then went back to being British by the WWII era. I have always seen it as a more British word. Here are the ratios, decade-by-decade:

Frequency of “philistine(s)” in British vs. American English [Google-Books]

1880: British, 2-to-1

1890: Parity, British edge

1900: Parity, American edge

1910: Parity, American edge

1915: American, 2-to-1

1920: Parity, American edge

1930: Parity, American edge

1940: British, 3-to-2

1950: British, 2-to-1

1960: British, 3-to-2

1970: British, 3-to-2

1980: British, 2-to-1

The word “philistine” had a huge jump in popularity in the USA in the year 1916, Google-Ngram shows. It went from .00002% (combined singular/plural) words printed in the USA in 1915 to .000106%, then back down to .000027% in 1917 (you can set smoothing to “0” to see this). This is a jump of 5x in one year. It must have to do with WWI. People were writing about WWI and the USA’s possible involvement in it. Some may have alluded to the Philistines of the Bible, who were sometimes at war with the Israelites (e.g., Goliath was a Philistine). Some of the Biblical uses (capitalized) of the word may have been read as lower-case by Google’s imperfect scanning software. Google’s Ngram software is not perfect. A similar bump happened in WWII in Britain, perhaps for the same reason.

Maybe the better word to look at is “Philistinism“, to get around that problem. Here are the graphs:

A long-forgotten, unknown pastor in a town in late-17th-century Germany ended up (in effect) “coining a word” that emerged in English two centuries later