Today’s genetic tests are able, with remarkable degrees of accuracy considering all that they have to go on is a vial of your saliva, to reasonably reliably estimate your ancestral origins. Not perfectly, but pretty well. (Maybe we have passed the point where intelligent people feel free or even compelled to say ridiculous things on this topic.)

I took the 23andMe ancestry test in February 2017 and a few weeks later got the results back. The “results” are percentage estimates for personal ancestry. I have some comments and thoughts on the results and related issues that I’d like to record here. I’ll compare the raw numbers to what I know of my documented ancestry and related ancillary information I know to fill in gaps.

The final section deals with the political implications of what is (purported) to be measured by tests like these and how people use and understand personal ethnic-ancestry identity. The political implications are substantial I think; this is the kind of iceberg issue that is mostly below the surface, unseen but enormous.

(Warning: Long post).

I have occasionally posted about this subject over the years on these pages, including:

Europe

First,

my father’s results. My father took the test about two years before I did. His reaction to his results was to the effect that there was nothing interesting in it, i.e., it was all as expected.

The general comments I would on his results are:

- 23andMe misguessed a substantial portion of my father’s ancestral-stock [17.9%] to be British, when in fact, as best we know, it is 0% British; all was in Scandinavia as of the mid-1800s. (Yes, British vs. Scandinavian is a pretty fine-grained distinction to make.)

- 23andMe gives my father a 51.0% Scandinavian estimate, when it should be 100%. The ratio of Scandinavian(correct)-to-British(incorrect) is less than three-to-one.

- A close analysis does reveal one ancestral component not otherwise known to us / not documented in the paper-genealogy records, which is Finnish. (Much more on this below and what I think is a plausible origin-story for it.) My father gets a 3.4% Finnish reading, which I seem to have disproportionately inherited. I get 2.3% Finnish, of which zero is estimated to be from my mother (see below).

- My father’s older brother took the test recently and got 10.0% British (much lower than my father’s, but again both should be 0%), 67.1% Scandinavian, and 3.8% Finnish (similar to my father’s).

Now, my own.

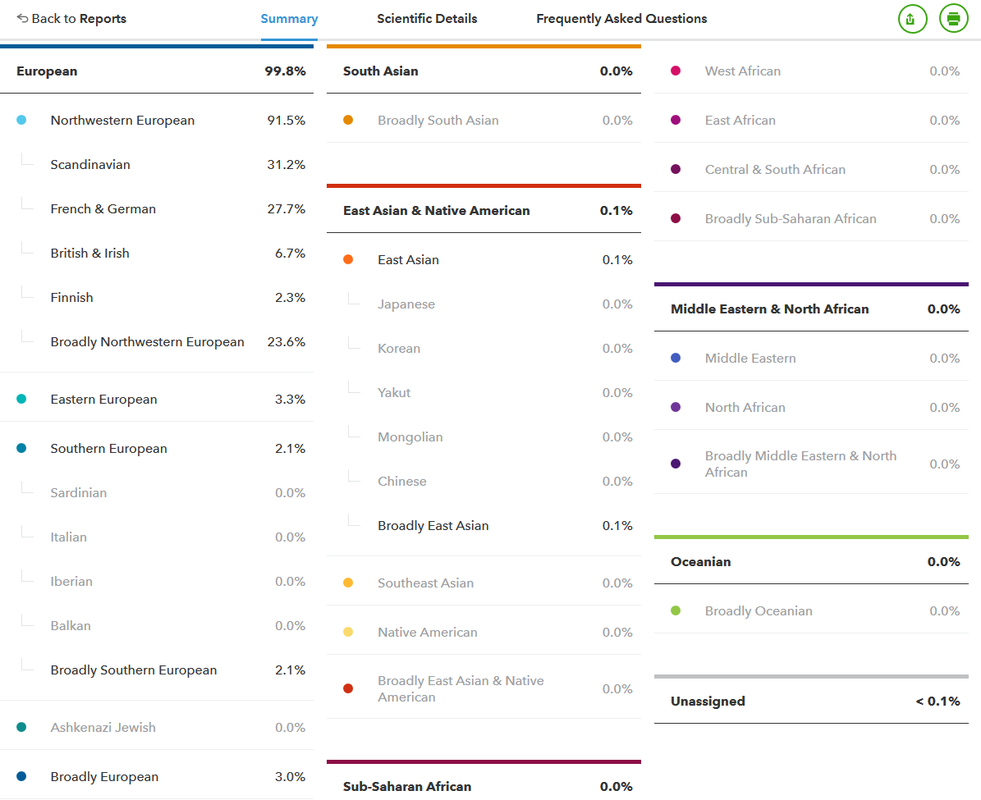

The table below contains my own comprehensive ancestry-estimate results:

Compare the 23andMe estimate for me (91.5% Northwest European, of which: 31.2% Scandinavian, 27.7% French/German, 6.7% British Isles, 2.3% Finnish, 23.6% Broadly Northwest European) to my

ancestors’ known places of residence in the middle 1800s:

- [Paternal] 50% Scandinavia

- 12.5% Denmark (patrilineal line traces back to the island of Funen [Fyn] circa late 1700s)

- 12.5% Sweden

- 25% Norway (Hedmark)

- [Maternal] Mainly Germany, some in New England (USA)

- 37.5% Germany (partilineal line traces back to Saxony; these German ancestors were all Lutherans)

- 12.5% Vermont (all with Colonial New England roots, patrilineally the Hazen family [see post-224] and similar families filling out the rest)

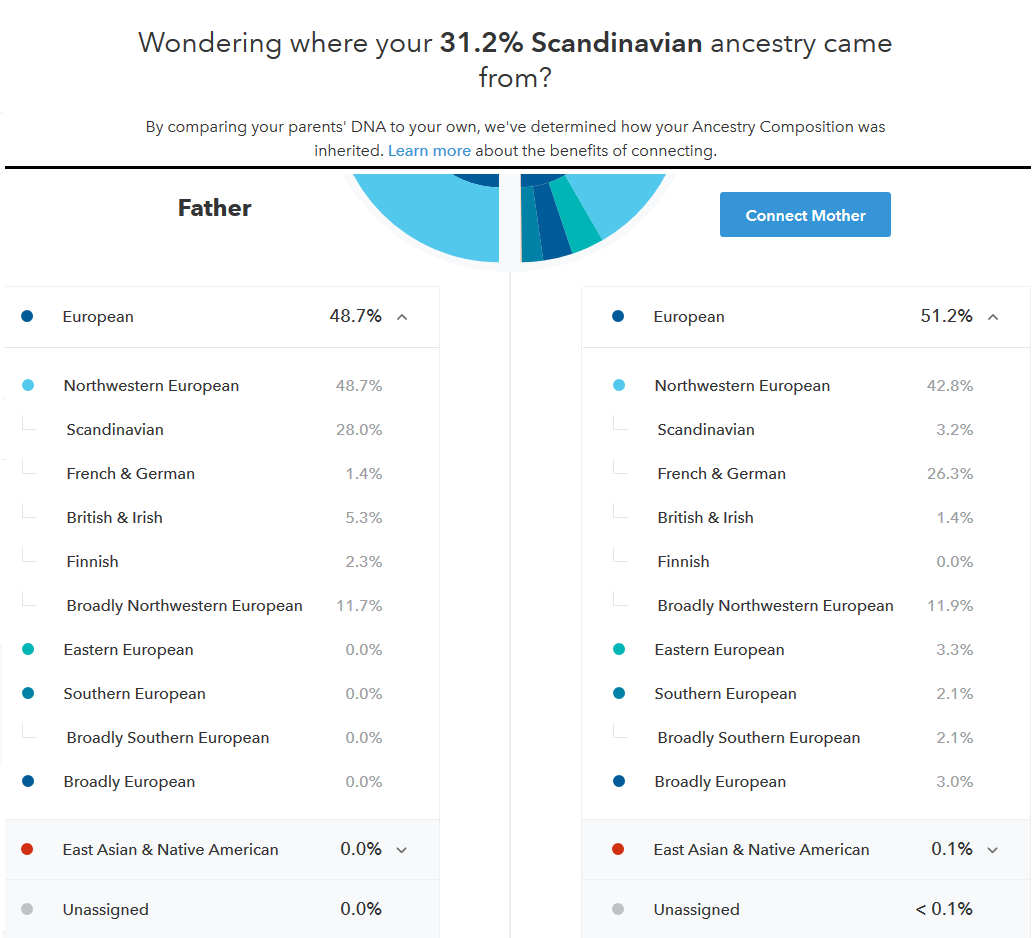

I stress what I know about the ‘patrilineal’ lines in the summary above because culturally we always know more about male lines. Whereas culture demands thing be simple, genetic tests can be very fine-grained: The system 23andMe uses can separate paternally-inherited from maternally-inherited DNA if you link your account with a parent’s. Naturally I linked mine with my father’s.

The following is the father(known)-vs.-mother(implied) breakdown for my own inherited DNA:

First, some comments on each major component:

[Father’s Side]

Scandinavian (Actual: 50%) (23andMe Estimate: 31.2%)

23andMe is said to generally underestimate the Scandinavian component and does so in my case. My actual ratio of Scandinavian-to-German ancestry is 133-to-100 (.5/.375) but 23andMe estimates exact parity, about 100-to-100 (both are at 31% if adding ‘German’ [27.7%] and ‘East European’ [3.3%], which will reflect eastern German ancestry).

The Scandinavian ancestral component for me includes the (historically) culturally important patrilneal line.

My father and my own Y-chromosome line is a branch of the greater European R1b family called R-U106 (see post-223), which is concentrated in Germanic Northwest Europe.

Paper-genealogy finds our patrlineal line’s origin many generations ago on the island of Fyn [Funen], Denmark, in the late 1700s. In 2015, in Korea, I met someone from this island, an experience I discuss in

Post-315 (“

Two Danes“).

Despite the continuing cultural importance of the patrilineal line, and while my father is aware of and acknowledges that his father’s line comes from Denmark, he has always felt much closer to his Norwegian ancestry.

All of my father’s Norwegian ancestry [50% of his total ancestry] seems to come from the region of Hedmark, which is very close to Lillehammer, site of the first Olympics I can remember (1994). They were farmers there, and like many Norwegian farmers, took family names based on the names of their farms.

This raises the question of why a person “chooses” to identify with (emphasize) a particular ancestry component and “neglects” (deemphasizes) other parts. In no particular order:

- Distance in time/generations;

- Language / mother language / exposure to language;

- Experience with older relatives of a particular origin/ancestry closer to the source;

- Experience with culture/traditions/religion;

- Surname: historically, patrilineal descent is important, as symbolized by (sur)name inheritance;

- Relative power or prestige of a given identity when and where a person grows up.

In my father’s case, his mother’s parents were both born in Norway, but his father’s parents were both U.S.-born (Miller, Iowa and Davey, Nebraska, respectively). This alone is already a big deal as per (1) above.

My father’s mother’s father was in Iowa from a relatively young age (Bert Sveen, 1876-1966, in the USA from 1882 or 1883), but his mother’s mother (Dena Kjendlie, 1880-1947) arrived around age 20, circa 1900 or 1901. These are two of my great-grandparents. Their daughter, my grandmother, spent her early years at home hearing mainly Norwegian, so the language component is there, too. My father and his brothers fondly recall eating certain Norwegian foods at home, and I got to eat these, too, when I visited Iowa, which means there was at least some symbolic connection to the ancestral cultural identity. As for the surname, our surname could plausibly be Norwegian (though it is actually from Denmark). Presumably, possession of an obviously non-Norwegian surname would reduce strength of any Norwegian identity.

The above are, I think, useful insights, but there remains point (6), which is what really interests me:

My impression is that ‘Norwegian’ is and always has been a more prestigious ancestry-identity in the Upper Midwest than ‘Danish’ or ‘Swedish.’ Why? Is it numbers? In absolute numbers, Sweden contributed more to the total U.S. White ancestral stock than Norway did (though in relative terms, relative to the home-country population, Norway contributed more.) I will return to this issue in the final section of this post.

Finnish.

(Actual: not known to have any) (Estimated by 23andMe: 2.3%)

Where does my father’s/uncle’s 3-4% Finnish and my 2.3% Finnish come from?

One might reasonably suppose that all Scandinavians get some small percent of ‘Finnish’ as a kind of background noise, reflecting not recent ancestry but some baseline level inevitable given that we are not Andaman Islanders and mixing has occurred. This is plausible and a reasonable supposition, but incorrect, or at least not correct in many cases. Browsing through some of the 1,000+ people’s profiles on the “DNA Relatives” feature of 23andMe, I see that some who list grandparents born in Sweden or Norway do have similarly low Finnish percentages to mine and my father/uncle, but quite a few, at least as many, also have 0% Finnish. One man with an 82.5% Scandinavian reading, the highest I’ve seen, all four of whose grandparents he reports born in Norway, gets 0% Finnish.

So Scandinavians will not necessarily have a low ‘background noise’ Finnish component. This is corroborated by the statistical methodology provided by 23andMe, from which I understand that 23andMe’s Finnish estimates are of a higher confidence than most of its national estimates, with an exceptionally low rate of false-positives. This is confirmed again when raising the highest confidence level, I still get 2.0% Finnish (and down to 5.5% Scandinavian).

A ‘Finnish’ reading from 23andMe, then, indidcates strong possibility that I have a relatively recent ancestor of entirely-Finnish or heavily-Finnish ancestry about six generations ago. Consulting the paper-genealogy records, this person was most likely born around the 1780s, 1790s, or the first decade of the 1800s, presumably in Finland.

_______________________________________

Here is my historical speculation on where the Finnish component may come from:

The Finnish Question

Finland was part of the Kingdom of Sweden for many centuries, a relationship that ended abruptly in 1808, at which time Sweden lost control of Finland to Russian forces. This was one of the last wars Sweden was directly engaged in, and it lost big (the last war was a brief war against Norway in 1814).

Finland under the Czars for 110 years, remained oriented in spirit towards the West and broke away immediately with the collapse of the Czarist regime in 1917. There is much to admire about Finland, as it fought successfully avoided ‘Bolshevization’ (with German assistance), preserved its independence through the turbulent next few decades, fought its famously valiant war, all alone against Stalin in 1939-1940, then again in 1941-1944, this second time allied with Germany.

Finnish leaders couldn;t have an endless run of good luck, though, and realized the time to ct a deal was at hand. Stalin guaranteed their independence in the late 1940s by informal and then formal agreement in which Finland promised to never attach itself to the Western security apparatus (this led some of our Cold Warriors to coin the term “Finlandization” to refer to a country adjacent to the Soviet Bloc partially detaching itself from the USA/West to appease Moscow; “Finlandization” was always the USSR’s goal for really all Western European countries, notably West Germany; at the high tide of Ostpolitik in the early 1970s, this effort reached a high-water-mark (only later did we learn just how mjuch Chancellor Brandt’s Ostpolitik administration was infiltrated by East German agents). Finland only “de-Finlandized” in the 1990s with the end of Soviet power, and is still partially “Finlandized,” if NATO membership is the standard. It is not and has never been in NATO.

1808-1809, anyway, must be seen as the dramatic turning point from which all subsequent Finnish and also Swedish history has followed, to an extent inevitably. With the loss of such an enormous amount of territory and the end of the military prestige it gained in the wars of the 1600s, Sweden became more-or-less been a neutral power, and has been once since. Like Finland, Sweden has never been a NATO member.

The historical experience of 1808 is critical. Consulting the genealogical records (via the work of my uncle C.J.), I see that 1808 aligns perfectly with the timing of when the hypothetical Finnish ancestor would have entered Sweden. I will try to explain this more below.

The Fall of (Swedish) Finland

What exactly happened in 1808? The Sweden-Russia conflict, which Sweden lost, was a Napoleonic-era war induced by Napoleon that lasted from February 1808 to September 1809. By 1808, Sweden and Britain were almost alone among European states still resisting the machinations of Napoleon. Denmark (which ruled Norway at this time) had been among the states puppetized by Napoleon. Russia was also on Napoleon’s side at this time. Napoleon would, a few years later, invade Russia with famously bad results, but in 1808 it was still allied to Russia.

Poor Sweden. In 1808, it ends up fighting two Napoleon-aligned states, Denmark/Norway and Russia, at the same time (Prussia had been neutralized two years earlier and could not assist Sweden). This was a strategic nightmare, and actually a close parallel of Germany’s dilemma of the first half of the 20th century: Encircled by hostile powers, allies distant or unreliable, ending up in a two-front war with one front being against the Russians. I read that for every man Sweden put in the field in the 1808-1809 war, Russia put between two and three, again paralleling the German manpower disadvantage of the following century.

Sweden’s military forces simply could not win a two-front war because it was forced to keep a large garrison away from the action to keep Napoleon-backed Denmark in check. (From Swedish Wikipedia [Google Translate:] “[In 1808-1809,] Sweden also had a knife tip in its back. Denmark was allied with Napoleon, and the French, in association with Russia, sent large troops to Jutland for a planned invasion of southern Sweden, and because of this threat, the Swedes were forced to hold large troops [in] Skåne and the Norwegian border.”)

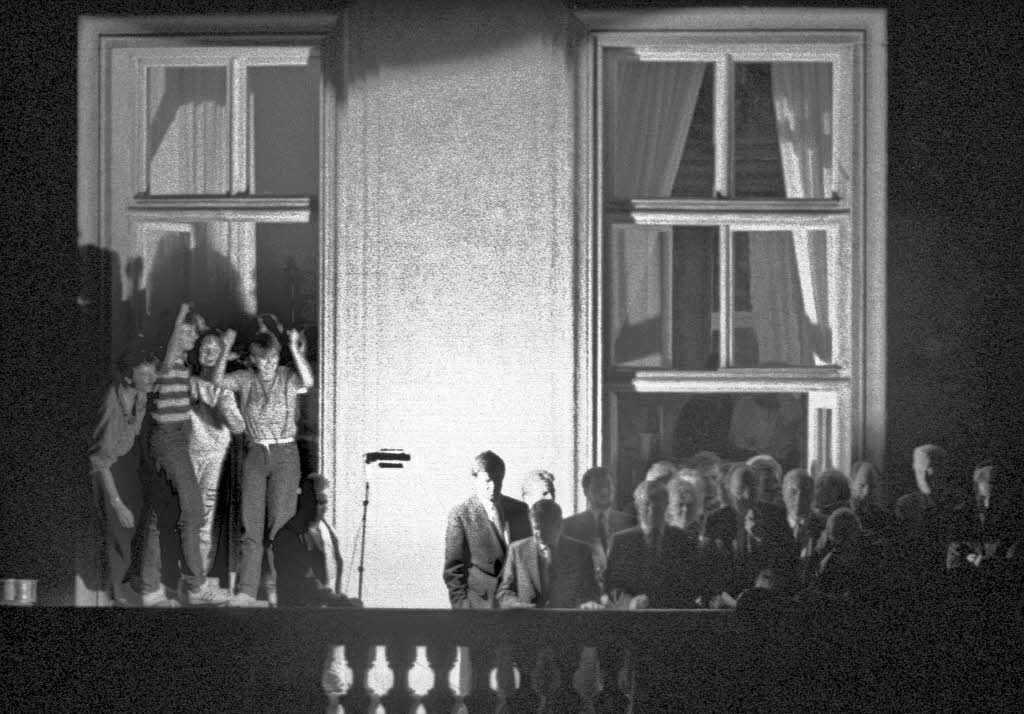

Reenactment of the Battle of Oravais (Sept. 1808), a decisive defeat for Swedish forces in Finland

Swedish Götterdämmerung, 1809

By March 1809, Sweden’s military fortunes are at their lowest point perhaps ever in history. Russian troops are in mainland Sweden moving on Stockholm itself. Is all hope lost? In another parallel with German history, Swedish generals conspire to take out their own ruler. Unlike the later German military plot (July 1944), the 1809 coup plan succeeds.

So we have Swedish officers staging a military coup d’etat and sending their own king into exile (he dies in Switzerland thirty years later, living in poverty under an assumed name). The new regime is a much more parliamentary one and negotiates a peace with Russia and Napoleon. Sweden cedes control of its large Finnish territory. Sweden itself is, to use an anachronistic term, “Finlandized” within the Napoleonic world for a time. To this day, Sweden has still only partially “de-Finlandized.”

Finland tries to make the most of things and begins several generations as a Russian possession, until Dec. 1917. (IThe Finnish Embassy held an open-air 100-Year Independence Anniversary party at Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C., in December 2017, which I saw at a distance.)

Fleeing Finland

I would propose that the Finnish ancestral component for my father and his brothers (3-4%) may come from one or more pro-Swedish individuals resident in Swedish-Finland in 1808, who fled Finland to Sweden proper, likely in 1808 or 1809. Once in Sweden, the person integrated into Swedish life, married a Swede, as did his or her son/daughter, and any trace of the Finnish origins melted away into the general Swedish population. Generations pass, and any knowledge of this Finnish origin was eventually lost. The last person who knew about it, if my theory is true, is probably very long dead now. Two hundred years later, evidence of it resurfaces via this test.

I have no genealogical record extending this far back to confirm this theory and I am open to alternative ones.

The most distant Swedish ancestors on whom I have information are a Charles E. Erickson (1848-1896) and an Annie K. Johnson (1850-1930), both born in Sweden. Both wind up in the U.S. Midwest by the 1870s or 1880s. I lack information on Charles’ and Annie’s personal ancestries. Both of these individuals theoretically contribute 1/8th (12.5%) each towards my father and his brothers’ ancestral stock, and 1/16th each of my own.

Using likely average age at childbirth. Charles’ or Annie’s grandparents were most likely born before 1808, perhaps in the 1790s or 1780s at the earliest. If any one of either Charles’ or Annie’s grandparents were among the Finns fleeing the fall of Finland in 1808 or 1809, that would account for this ‘Finnish’ 23andMe reading: Each one of Charles’ and Annie’s collective eight grandparents theoretically constitute 3.125% of my father and his brothers’ ancestral stock, which is about exactly the result implied by my father’s estimate. The numbers just line up perfectly.

I find online that a Dr. Markku Mattila of the Migration Institute of Finland notes a large exodus from Finland to Sweden in 1809 with the loss of the war, which adds plausibility to this hypothesis.

I note again how comparable this theory is to a later exodus event, involving similar players and a similar situation: those who fled Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania in 1944 as the German defense effort began to falter and a Red Army re-takeover looked inevitable.

The USSR’s invasion and subsequent 13-month reign of terror 1940-1941, before the Germans came in [July 1941], was the profound trauma for Latvia and Estonia (at least) in the 20th century. The Estonian national museum primarily revolves around this trauma, the 1940-1949 period but especially the terrible 1940-1941 period of Soviet terror, which so badly psychologically wounded the nation, and which cost the lives of a good portion of the Estonian elite of the day.

I understand that about 15% of the Latvian/Estonian population fled west with the retreating army in 1944, abandoning homeland towards an uncertain future. One of these was the mother of Svante Paabo (b. 1955), a renowned Swedish biologist. She was an Estonian and fled Estonia in 1944. Another, a so-called Displaced Person from Latvia, lived for a period with my mother’s family in Connecticut in the early 1950s.

[Maternal]

German. (Actual: 37.5%) (23andMe Estimate: 27.7%)

I have never been able to confirm regions of origin for most of my German ancestry. I know with certainty only the regional origin for one branch, my mother’s father’s patrilineal line: That is the region around Leipzig, Saxony.

My great-great grandfather through this line, Gustav K. Sr. (1857-1917), served in the German Army as a conscript from 1879 to 1882 (peacetime). I have held his original military service booklet in my hands. It was preserved all these years, 135 years and counting (though increasingly fragile and faded), by descendants, including my grandfather and now aunt in Connecticut. The seervice booklet lists his place of birth (in 1857) as “Klein Goddula,” a small village now part of a larger jurisdiction called Dürrenberg, which has been renamed “Dürrenberg Spa Town” (Bad [Spa] Dürrenberg) to promote tourism).

Gustav K. at some point movies to the big local metropolis, Leipzig and becomes involved in the printing industry, but leaves Germany forever in somewhat unclear circumstances in 1887 (more on this shortly). His wife Emma Kretchmar (b. 1858)’s surname is highly concentrated in Saxony, strongly suggesting she was a local too. As for the surname K., it is the name of two villages, one in Saxony, and one in an adjoining region of Germany.

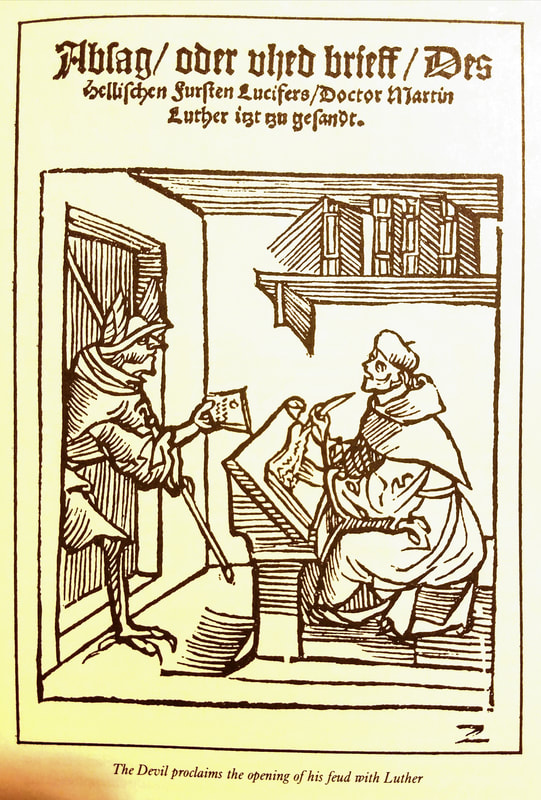

The two above-named 19th-century Germans (who were in the USA in their 30s and until their deaths) each constitute 1/16th — and thus together 1/8th [12.5%] — of my own ancestral stock. As for the other 25% German to account for, as I say I have not been able to confirm their origins with certainty. I do know that they were all Lutherans.

This map of the political situation in central Europe in 1789 may be helpful. The Electorate of Saxony, in orange, is the origin of the two above-named people. It was one of the larger German states (there were dozens or hundreds of German or quasi-German states and “statelets” at this time. Blue and teal (not purple) were areas under the control of the Hohenzollern Dynasty (which mainly means Prussia, capital Berlin. It would go on to unite Germany, excluding Austria [Bismarck did not want them in] by 1870.)

I have speculated that my ancestor Gustav K. Sr., who was born after the territorial realignments of 1815 that came with the end of the Napoleonic Wars but before German unification, inherited a cultural loyalty/romantic-affinity for Saxony, and a complementary mild antipathy towards Prussia/Berlin. His hometown had been one of the many parts of Saxony handed over to Prussia in 1815. He would not be born for a few more decades, but by the 1860s and rapid movement towards German unity under Berlin may have caused a minor revival of local resentment. If this is accurate, this may have been a seed of the discontent that later contributed to Gustav’s involvement as a young man in dissident politics in the Leipzig of his day.

Lots of other things were going on during Gustav K. Sr.’s time in Germany, including the beginning in earnest of Germany becoming an urban industry-oriented state. Gustav himself was born in what must be called a hamlet. Likely by adolescence or so, he in one of Germany’s leading cities (Leipzig). The cultural disorientation of country-to-city movement no doubt also contributed in some way.

As far as I know, both before and after his mandatory military service, Gustav was in the book-binding industry in Leipzig (1870s and 1880s). His decision to leave Germany in 1887 came after he was fined by the government in unclear circumstances. We assume this was related to publishing. My grandfather understood the matter to have been related to the political push then-current in Bismarck’s Germany towards what we now would call social welfare politics. This was the era of the rise of the Social Democratic Party in Germany (See this Wikipedia article for more on this.)

Whatever the specifics of it were, Gustav K. Sr. was ahead of his time, and almost all forces in later German politics, across the political spectrum, would call for similar programs as a matter of course. But Gustav was done. Who wants to stick around when you’re on “the list” of the secret police? Greener pastures await.

Gustav K. Sr. would go on to co-found a German social club in New Britain, Connecticut, remained active in the Lutheran Church, as did several subsequent generations of American-born descendants of his. Gustav is listed by census takers on the 1900 U.S. Census as a “saloon keeper.” He died just before Prohibition came in, which he certainly would have opposed.

Gustav K. Sr.’s son (my great-grandfather, Walter K [another son was named Gustav K. Jr.]) would follow his father in the publishing industry in the Connecticut of the 1900s and 1910s. Walter K. worked in newspapers, but a workplace accident when he was about thirty left him partially disabled and limited his life prospects.

Gustav K. Sr.’s grandchildren (including my grandfather) largely retained a significant German identity, and my grandfather spoke German quite well, though was certainly more comfortable in English. I later studied German with some success, but studied it purely as a foreign language; I “inherited” no German (or any other) language at all.

Eastern European. (Actual: None Known) (23andMe Estimate: 3.3%)

The East European component in the 23andMe result most likely reflects eastern-German ancestry. I expect a baseline level of Eastern European reading for Germans from regions of eastern Germany, like Silesia (see map above), and anywhere that was in the pre-partition Kingdom of Poland.

The alternative hypothesis is that this could be of morw recent origin, and an actual full- or partial-ethnic-Pole, one of the several million in the former eastern regions of Prussia/Germany in those days.

One famous German with a partial Polish origin whose story may be helpful here is Chancellor Angela Merkel. Her grandfather (1896-1959) was a German citizen and a veteran of the 1914-1918 war on the German side, but had a Polish surname and is considered by historians “ethnically Polish,” making Merkel 1/4 Polish by ethnic-ancestry, though 4/4ths German by citizenship-ancestry.

This ‘Polish’ grandfather of Merkel’s opted to retain German citizenship after the creation of an independent Poland in 1918 and ends up in Berlin by the 1920s. His son, Merkel’s father, ends up a West German Lutheran pastor who entered communist East Germany in the 1950s to set up a church mission. His rhetorical support for the Socialist project of the East German regime apparently earned him the nickname The Red Pastor by some colleagues in the German Church at the time; some critics to Merkel’s right in our era have repopularized this to impugn Merkel herself, especially now with the rise of the anti-Merkel AfD party.

I relate this story of Merkel’s grandfather to show how fluid “ethnic-vs.-nation” identities can sometimes be, even in the past. The point is a similar case, about a century earlier or more, could make up for some or all of this East European component estimated by 23andMe. In this case, I do tend to think it is largely or entirely a baseline rate.

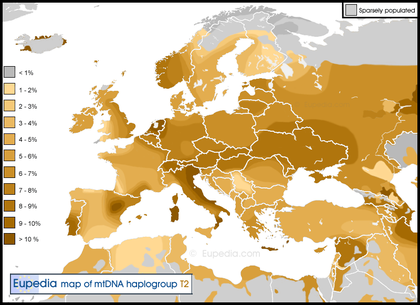

Southern European. (Actual: None Known) (23andMe Estimate: 2.1%)

I do not likely have Southern European ancestry. I can say with confidence that this particular 2.1% reading is a “false positive” as a closer look at the results shows that the entirety of it (2.1% Southern European) comes from the mtdna (the mother’s mother’s mother’s…[etc.] line). It is entirely on the X chromosome and not on any of the other 22 chromosomes.

My mtdna line is T2a. “Nearly 10% of Europeans can trace their maternal ancestor to Haplogroup T.” Here is a map of the regional distribution of T2a. It is widespread across Europe. Because it is slightly higher in parts of Southern Europe, it is classified as Southern European only because, I suppose, they have to classify it as something. 23andMe lets you lower the confidence interval, and at higher confidence levels, the Southern European reading disappears.

So what is the earliest known origin of my maternal line? The earliest name/place I have for my mother’s mother’s (etc.) line is a Justine Bucholz (nee Baumgarth) (1866-1920), born in Germany and died in Connecticut. As with many other of my mother’s relatives, she and her husband are buried at Fairview Cemetery, New Britain, Connecticut. I was surprised to see that their gravestone is written in German (

here is a picture).

I do not know with certainty Justine Baumgarth’s specific regional origin in Germany, but surname analysis finds that a close variant surname, “Baumgardt,” is relatively concentrated in the Kassel region of Hesse, Germany, a Protestant region since the early Reformation era. which had a Lutheran majority and Protestant supermajority (90%+) when my ancestors left Germany.

Where is the Colonial New England Ancestry? (Actual: 12.5% )

One of my great-grandfathers, Earle Hazen (see

post-224), was of (entirely) Colonial New England ancestry.

Earle Hazen’s ancestral lines are documented back into the colonial era. These days, with just a few names, it is easy to rapidly expand an ancestral tree through what others have put online. My investigation finds that either 15/16 or 16/16 of Earle Hazen’s personal ancestral lines were in the U.S. in 1776.

The surnames I see among the Earle Hazen ancestors are mainly English (Hazen, Knight, Knowlton, Darrow, Bell, Deuel, Blackman, Foster, Thurston, [Unknown], [Unknown], [Unknown], Lougee, Folsom, Goodale, [Unknown]). The name Lougee I thought might not be English, but turns out to be from the isle of Jersey, an island in the English Channel and a British possession since the Middle Ages. The French surname ‘Deuel’ is U.S.-born going way back and I presume Huguenot.

The first Europe-born ancestor in this line I have located is British subject William Bell (b. 1769), who is in the USA by 1794 at the latest (his year of marriage, recorded on U.S. soil). He was the great-great-grandfather of my great-grandfather Earle Hazen. Of the other 15 (great-great-grandparents of Earth Hazen) of this William Bell’s generation, six are known to be born in New England, one known to be born in New York, and eight have unknown birthplaces but are known to have lived as adults either in New York or New England, primarily Vermont.

Anyway, this line should be primarily, even overwhelmingly, British Isles, with small amounts of other mainly Northwest European components typical of New England Colonial stock. 23andMe estimates very little British Isles from my mother, so this ancestry hardly even leaves a trace in the 23andMe data. 23andMe assigns my mother only 3% British Isles ancestry (implied, see above), though she should actually be over 20%. It also assigns my mother 6-7% ‘Scandinavian’ which must also be miscategorized Colonial New England British-Isles ancestry.

Yes, it’s strange, but the entire Colonial New England component fades away at a bird’s-eye-view level in the 23andMe data.

Concluding Thoughts: On the Politics of Ancestry-Identity

Partial identities always fade away. It is the rule and not the exception. Actually, though, there are many exceptions. Some identities are much more successful than others.

In the ‘Scandinavian’ section far above, I discuss a bit about factors that may contribute to the relative success of competing ‘national’/ethnic identities in White Americans and other Whites outside Europe, and perhaps increasingly also inside Europe. I believe this is a seldom-seen and undiscussed but important part of our social fabric and worth thinking about more.

In line with some comments breezed past or implied throughout this essay, I can say that there are rarely “clean” identities, and components of identity are always subject to emphasis or deemphasis given changing cultural and political conditions, or personal preference, or some other reason. That is, genetic ancestry and ancetsral-ethnic identity are not the same; they are overlapping concepts but not identical, and people can and do pick-and-choose from components of their own identities to form their own or the one they present to others. This may be obvious, but is worth looking at directly.

People will also often universalize one particular identity (that is, to make one single ancestral-ethnic identity subsume all others when multiple possible ancestry categories are possible for them). It is laughable to “identify” as 3.4% this, 5.6% that, and so on. People need simple categories, and in places with multiple ancestral currents coming together (the situation of all societies at some level), every individual has to engage in a kind ancestry/culture-identity selection to smooth things over. Even those with very low awareness of their own ancestral origins do this.

This not only applies to people with multiple strains of ancestry from various nation-states, but to really almost all of us, as possible conceptualizations of ancestral-ethnic identity include the regional-subnational (like a specific region of England instead of ‘England’) or para-national (‘Scandinavia’ instead of Norway), and other factors. States, of course, rise and fall, and with them possible identities fade and successor identities must be born.

What if someone had a “Holy Roman Empire” identity in 1800? That awkward, lumbering pesudo-state was dissolved by Napoleon. What were the successor identities? Often based on language, but also based on other factors like religion (German Catholics on the margins of the German world, for generations maintained a kind of sullen, malcontented quasi-ethnic identity, always against the German mainstream, kind of like today when a minority political party seeks only to block legislation by the other guys; this was much to the annoyance of Bismarck, which is what led him to deliberately exclude Austria from the new Germany.

Back to the question of what leads an individual to emphasize and/or deemphasize/ignore/suppress a component of his/her ancestral identity? I would here propose the concepts of “high-prestige identity” and “low-prestige identity,” concepts which are directly related to political dynamics/power even if not exclusively so. I don’t have an easy formula for what makes an identity high prestige and another lower prestige, but just identifying the concepts may be useful.

High-Prestige Identities

What are some examples of prestige identities?

I would say that a (high-)prestige identity is one that the culture encourages or promotes in some way, and to which ‘converts’ or admirers are attracted. In ancient history, at its peak the Roman Citizen identity was a good example. In more recent times in the USA, the WASP identity was a prestige identity (though not in several generations now).

A good example from the present in the USA is the Jewish identity. It emerged in the past few decades as a high-prestige identity. Jews are proud of being Jewish, marginally-affiliated Americans seem also to be attracted to the Jewish identity and try associate with it, and Jewish ancestry is usually emphasized, all of which form a good working definition of what I mean by high-prestige identity.

(This tendency for partial-Jews to emphasize their Jewishness is even true when the non-Jewish half is Nonwhite, like the two daughters of author Amy Chua, whose husband is Jewish: after reading the famous Amy Chua book called “Tiger Mother” some years ago, I found the daughters’ public blogs and social media accounts, and both seem to identify more as Jews; one of them is a major promoter of Israel and IDF fan. They seem to have little emotional investment, by contrast, in their Chinese 50% ancestry.)

It is possible to quantify this. Pew Research has data that support my impressions to the effect that Jews married to non-Jews report raising their children Jewish by about two-to-one. Other polling data suggests that while ‘Jews By Religion’ are only 1.8% of the U.S. population, people identifying as being of Jewish background, partly Jewish, or of “Jewish affinity” (“people who were not raised Jewish, do not have a Jewish parent, and are not Jewish by religion but who nevertheless consider themselves Jewish in some sense”) more than double their numbers to 3.8%. Despite relatively low fertility, Jews have expanded their share of the U.S. White population in the past fifty years, specifically explainable, I think, by the relatively high prestige our culture attaches to that identity.

(Those who do not believe that the Jewish identity is a high-prestige identity in our society today, I would invite to watch video of the AIPAC Conference. The yearly one has just wrapped up.)

What is another example of high-prestige identity, closer to home for me? To find one, reading through old books would do, beginning in the Romantic period of the 19th century and extending well into the 20th, in which writers extol their membership in the Germanic family of nations (using any number of then equivalent then-vogue terms).

In the 23andMe ancestry category framework, roughly they meant the “Northwest European.” I am thinking of people like Rudyard Kipling. Theirs was an era when such a thing, conceptually, was high prestige.

Consider that Norwegian cultural leaders before the 1914 war began spoke in such terms as these:

I’m a Pan-Germanist, I’m a Teuton, and the greatest dream of my life is for the South Germanic peoples and the North Germanic peoples and their brothers in diaspora to unite in a fellow confederation.

These were the words of Bjornstjerne Bjornson in 1901, one of Norway’s greatest writers and author of Norway’s national anthem. (This was shortly before Norway’s own independence in 1905.) Plenty of other leading Norwegians spoke in terms like this, too.

Low-Prestige Identities and ‘Out’-Identity Coping Strategy

People signal their disassociation with low-prestige identities. No Norwegian today, or really anyone else with a public image to maintain, would ever say something like what Bjornson said in 1901, and anyone who does so in a public forum would be either derisively laughed at or condemned. Why?

The answer is that the para-national identity or meta-identity implied by Bjornson’s words actually serves a negative function in today’s world. It is almost an anti-prestige identity. Bjornson, a leading cultural figure in Europe of his generation, if alive today would much more likely say something nearer the opposite: “The greatest dream of my life is More Syrian Refugees!” Why would he demand more Syrians? He would feel pressure to signal that he is not someone affiliated at all with those bad people who would promote the low-/anti-prestige identities like this high-culture, Nobel Prize-winning monster Bjornson promoted.

An important extension of the concept of low-prestige identity is that people of the low-prestige-identity background seek a “Way Out.” For ethnic ancestry, there is not necessarily a direct way “out,” with some oddball exceptions: I recall the recent case of that one White NAACP activist who pretended for years to be Black before being expelled from the group for pretending to be Black. What to do, then? Emphasize or conjure up (in some cases from little or nothing) some kind of exotic ancestry.

A large number of Whites in the USA vaguely claim distant American-Indian ancestry. 23andMe and similar genetic tests reveal that the large majority of Amerindian ancestry claims by White Americans are at least exaggerated and often totally false. (A well-known U.S. politician was one of the many who have falsely claimed Amerindian ancestry; she was either deceived by someone else in her family on this [her story] or deliberately deceived others possibly to get admissions preference at university [her opponents’ story].)

Self-predicted American-Indian ancestry among Whites is much higher than actual tested ancestry. It turns out that under 0.2% of total White ancestral stock in the USA is classified under 23andMe’s Native American category, according to one large peer-reviewed study. The sociological-political dimensions of this, I think, are obvious.

Ethnogenesis in Colonial North America

A specific example of an ancestry-identity that is almost always deemphasized in the USA, perhaps inevitably, is the English/British. Even though something like 30-35% of White-American ancestral stock is British-Protestant, we rarely, if ever, hear anything about that as an “identity” at all. The English element especially of a White American’s ancestry is, I think, the most likely to be ignored entirely, and is almost always and inevitably deemphasized.

One reason for this could be that a new defacto ethnic group was born in North America in the colonial era. Just like Whites in colonial-era South Africa successfully formed an entirely new, legitimate ethnic identity (the Boer/Afrikaner), one could argue that Americans had done so, too, by the late 1700s and early 1800s. I believe this. Subsequent immigration from Europe was so large in scale that competing European identities emerged (reemerged), which remain with us to this day despite tenuous-at-best connections to the ancestral homelands for most of us.

The Future

The few hundred million of us of European (especially, in my view, Northwest European) ancestry across the world today do seem to be encouraged to think of ourselves as nonethnicized “default people” of our countries of residence. It is other people who have legitimate identities, not us Default People. This is something I have consistently picked up on from our culture since high school, and I have always been uncomfortable with it.

So what next? As a process, this kind of thing never comes to a halt. It has not in the past, and it will not in the future.

This may partly explain the interest some of us have in genealogical investigation: It is not simply something of the past, but something which informs the future. After all, how is the future ever defined except in terms of the past?

[End]

Postscript: Scenes from some of the places mentioned in this essay or similar places.

Northern Lights / northern Sweden

“Egeskov Slot,” a castle (built 1554) on the island of Funen [Fyn], Denmark. My ancestors had nothing to do with this but were relatively close by. Two direct paternal ancestors (one 1795-1875 and one 1828-1913) were born in Strandelhjorn, Denmark, ten miles from this castle.

Hedmark, Norway

Glomdal Folk Museum, Hedmark, Norway

Hedmark, Norway

Faroe Islands

Halle, Germany, Christmas Market (2013)

From Bad Duerrenberg, village in Germany, birthplace of my mother’s father’s father’s father (1857)

Hotel in Bad Duerrenberg, Germany (now a resort town)

[Note: This was begun in September and October 2017 and left as a draft; finished in March 2018].