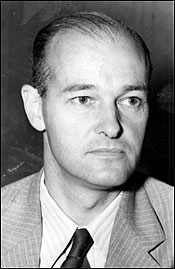

He was in the U.S. foreign service in the 1920s-1940s, ambassador to the USSR for a time, a great linguist, and a great thinker; a brilliant man. He was one of the USA’s foremost experts on European affairs, especially Russian affairs. His wife was Norwegian. He drew up the USA’s “containment” doctrine and the Marshall Plan, essentially laying the groundwork for fifty years of U.S. policy in Europe (which became anachronistic after 1991 but sort continued on in mutated form anyway; I wonder what Kennan thought about the interventions in Yugoslavia? Kosovo? Crimea?).

Kennan was one of the only voices in the U.S. government in 1945 and early 1946 who warned that Stalin was not to be trusted, that Stalin was aggressive and intransigent.

It sounds like Kennan was a “good old fashioned” American patriot. He was not. Recently I read (some of) a book called George Kennan: A Study of Character by John Lukacs (2007). In it, we see that Kennan actually grew to dislike the USA:

What [George Kennan] saw [from the 1930s onward]…was no longer a world of his. He would, because he must, remain loyal to his country. “But it would be a loyalty despite, not a loyalty because, a loyalty of principle, not of identification.” [quoted text was written by Kennan in the 1960s]

He [Kennan] blamed much on the automobile. He found a civilization dependent on automobiles deleterious. He remembered one of his professors in Princeton who explained that railroads, coming into the centers of towns, contributed to the growth of an urban civilization, while the asphalt roads extruding from cities lead to their dissolution.

Still — whether “despite” or “because” — there could be no question of [Kennan’s] loyalty to the Foreign Service. …[T]here was, too, a puritanical streak in Kennan’s character: a categorical imperative of duty.

Fareed Zakaria, U.S. media darling, wags his finger disapprovingly at recently-revealed comments made by Kennan:

Writing on a flight to Los Angeles in 1978, Kennan thinks about how few white faces he will see when he lands and laments the decline of people…“from whose forefathers the constitutional structure and political ideals of the early America once emerged.” Instead, he predicts, Americans are destined to “melt into a vast polyglot mass, . . . one huge pool of indistinguishable mediocrity and drabness.”