The war ended in July 1953. This movie was made in 1954 and released late that year.

The movie is set during that long, cynical stage of the Korean War without a clear and decisive objective and without the intention of victory. American policy was deliberately to “not win the war” starting in spring 1951. From then on, strategic policy was to fight for a status-quo stalemate. (Parallels to Vietnam are here for the taking.)

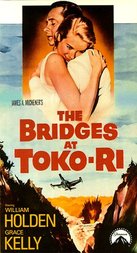

Now, “Bridges at Toko-Ri” is not what you’d expect. In theory, it’s about the war in Korea. In fact, we see hardly any “War” and even less “Korea” (i.e., there is very little combat and very little of the movie takes place in Korea itself).

Here is one: During a “mission briefing” scene, almost every single character is puffing away on a cigarette. If you look closely below, you can see four or maybe five of the men with lit cigarettes. The leader is puffing on a big cigar. You won’t see this so much these days. It surprised me to see smoking on a Navy vessel in the first place. Apparently it was done a lot, but is on the way out according to “Smoking in the United States Military“wiki article.

Everything about this character/man fits a certain archetype in pre-1970-or-so American cinema that we seldom see anymore, I think: The “Artistocratic-Yet-Rugged Heroic American Male”: Admirable; honorable; noble. A certain accent, a certain manner, and a certain look. Today, this William Holden would much less likely be cast as the quintessential, timeless American Hero, and much more likely as the “quintessential” Villain!

But it is still 1954. A man like Brubaker is still a heroic figure to be looked up to.

Much else about the Japan of the 1950s seems “embryonically South Korean” (as I’ve known SK since 2009). Here is a shot of some of the pilots going to a bar off-base in Japan. This neon-dominated building looks South Korean, too:

(These two things are trivial, but point to the bigger message of just how much South Korea [and maybe others in Asia, too] borrowed/appropriated from Japan — including the entirety of their “chaebol” economic model .)

For something completely different: I found this interesting. “Beware of Props and Jet Blasts”. This use of “props” has a funny double meaning, being as this was a movie. It means “propellers”, it seems, in Navy jargon.

Brubaker is a successful lawyer and family man. He flew planes in WWII. Brubaker is called up to fly again in Korea but is ambivalent about the war. The movie opens with his plane shot up terribly after a mission against the Communists. He manages to make it back over the water and bails out. He is saved by a helicopter crew. The admiral takes him aside after he is saved and asks about his experience of being “fished” out of the water:

Admiral: Well, those helicopter boys are pretty good fishermen.

Brubaker: As far as I’m concerned, they deserve every medal in the book. You’re out there all by yourself. You know you can’t last very long. You’re scared and freezing. You curse and you pray. Suddenly you see that mix-master whirling at you out of nowhere. […]

Admiral: Well, I’m mighty glad they pulled you out, son. […]

Brubaker: You do a lot of thinking at a time like that. Mostly about your friends who are back home, leading perfectly normal lives.

Back to the plot: As one of the best pilots in the Navy, Brubaker is assigned to destroy the bridges at a place called Toko-Ri. They are very heavily defended, and it’s clear that the pilots on this mission have a high chance of death.

Here is the scene in which the mission is explained, with the admiral’s justification, with the politics of the war and the entire Cold War itself weaved in gracefully:

Brubaker: Well, sir, the organized reserves were drawing pay, but they weren’t called up. I was completely inactive, and yet I was. I had to give up my home, my law practice; everything. Yes, I’m still bitter. [….]

Admiral: Nobody ever knows why he gets the dirty job. And this IS a dirty job. Militarily, this war is a tragedy.

Brubaker: I think we oughta pull out.

Admiral: Now that’s rubbish, son, and you know it. If we did, they’d take Japan, Indochina, the Philippines. Where’d you have us make our stand, the Mississippi? All through history men have had to fight the “wrong war” in the “wrong place”, but that’s the one they’re stuck with! That’s why one of these days we’ll knock out those bridges at Toko-ri.

Brubaker: [Nervously] Do we have to knock out those particular bridges?

Admiral: Yes, we must. I believe without question that some morning, Communist generals and [sarcastically] “commissars” will hold a meeting to discuss the future of this war. A messenger will run in and tell them, “They’ve knocked out even the bridges at Toko-ri!” That little mission will convince them that we’ll never stop! Never weaken in our purpose. And that’s the day they’ll quit.

Brubaker, suitably, is the American Mainstream: Ambivalent about the war at best, leaning against interventionism: “Why am I here? Why don’t we get out of here? What’s the use?”

Brubaker, in another scene, tries to bail his helicopter pilot friend out of military jail after a fistfight:

Brubaker [smiling, hands in pockets]: He also saved the lives of four pilots.

M.P. Jail Official: Lieutenant, I’ve got a lot of monsters back there in that “birdcage” [a U.S. military jail cell in Tokyo]. Every one of them was a hero in Korea. But here in Tokyo, they’re all monsters.

Near the end of the movie, after a series of unfortunate events for the Americans, a fatalistic Brubaker addresses this issue again.

Brubaker: [Muttering] The wrong war in the wrong place. That’s the one you’re stuck with.

Helicopter Pilot: What’d you say, lieutenant?

Brubaker: Did you ever hear Admiral Tarrant go on about this war? About the chosen few who have to lay it on the line? I can see now he was right. You fight simply because you’re here….

[Spoiler Below]

Brubaker is hit by the Communists during the Toko-ri raid, and loses too much fuel to make it back to the aircraft carrier. He bails out near the coast, but still on land. The same helicopter crew that saved him in the opening scene shows up again. The helicopter is shot down by more Communists. They bail out and join Brubaker for a last stand. The helicopter crew members are killed one by one. In the final scene, Brubaker himself is killed shortly after making the speech above.

Thoughtful review Peter. I was 10 years old and remember the war as a favorite topic among the adults. George Clooney be cast as Brubaker in a remake? Read the James Michener book – he was riding an aircraft carrier looking for a story.

I didn’t realize it was based on a novel (by James Michener, as you say). I see it was published in 1953 and inspired by a helicopter rescue of a stranded pilot at sea, which the author witnessed.

I think a remake would be a good idea. Some of the themes of the movie remain relevant today — The question of foreign interventions; the fleeting nature of glory (“Every one of them was a hero in Korea. But here in Tokyo, they’re all monsters”).

I am not aware of a single Korean War movie coming out of Hollywood in the 1990s, 2000s, or 2010s so far. Why is this?