Earle probably read this news in a newspaper, as this was before even radio. He’d not have been able to predict that a century later, his great-grandson (me) would be typing these words about him, wondering how he learned of the war.

Of course, what we now call “World War I” didn’t immediately affect him, nor many other Americans. The USA insisted on staying out of that irrational and deeply cynical war in its first few years. President Wilson famously ran for his second term in 1916 under the slogan “He Kept Us Out of the War”.

In time, the war came for us, too. Spring 1917. The very week that the USA declared war on the German Empire in April 1917, my great-grandfather, Earle Hazen, turned 20. As this is prime conscription age, he ended up in the army.

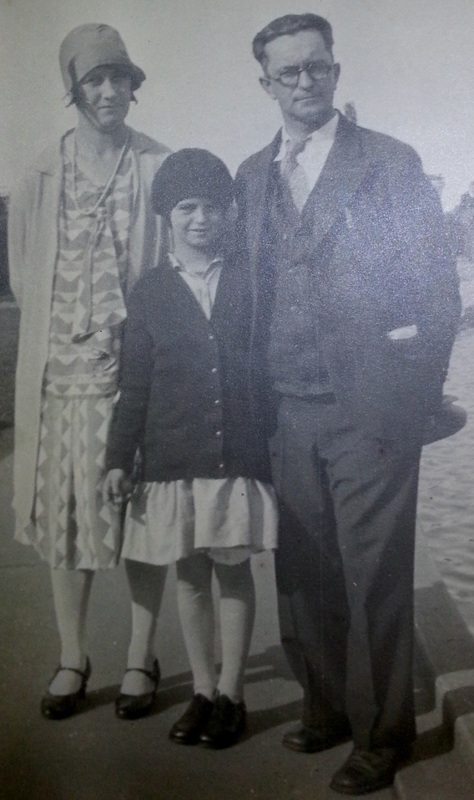

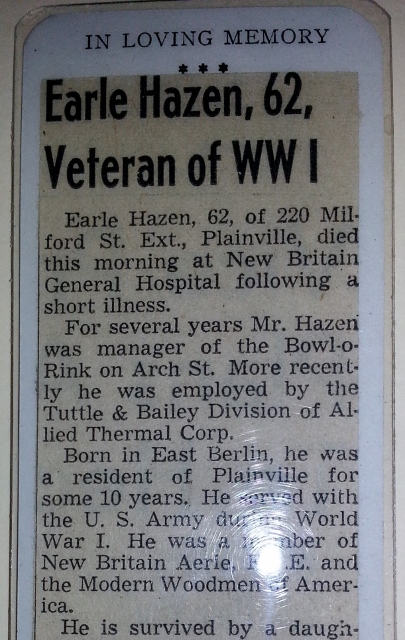

Earlier this year, my cousin N.D. and I found a picture of Earle Hazen in the attic of the old house in Connecticut. The girl in the picture is our grandmother (born in 1921). Judging by her age here, this picture seems to be from around 1930. My cousin N.D., upon seeing this photo, insisted that Earle Hazen at that time looked a lot like N.D. does today.

What do I know about Earle Hazen? I know the following:

Not long after finishing up with his bit in defeating the Kaiser, Earle decided that the logical next step was to marry a German (what else?). (She’d come to the USA in 1907 at age 8 with her older sister.) Their daughter is my grandmother.

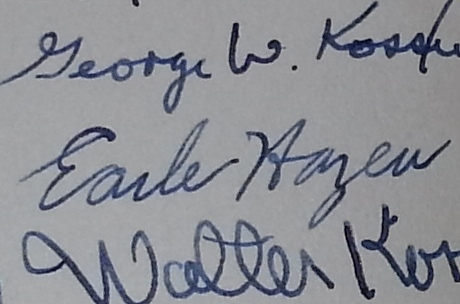

Few still living today can testify much to Earle’s personality as he died so long ago. Those who know handwriting analysis (not me) might be able to glean something from this:

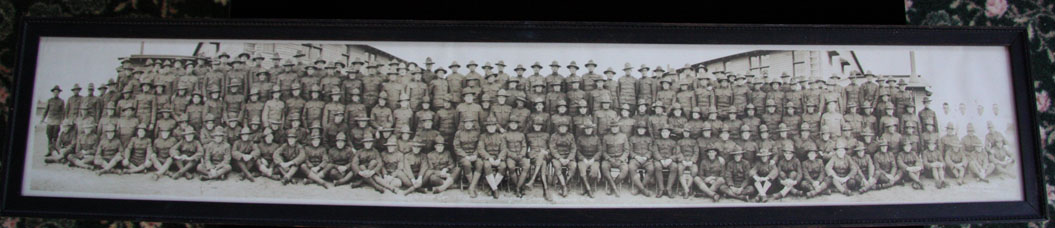

Earle Hazen is the only one of my four great-grandfathers who served in that war. (Another great-grandfather, in Iowa, was of prime service age in 1917 but was exempted for being a farmer, I think. His cousin of the same name served.) Earle Hazen was in the U.S. Army’s “151st Depot Brigade” (3rd Company) which was stationed at Camp Devens in Massachusetts. Here is a photograph somebody is selling of another of the 151st’s companies in 1918:

|

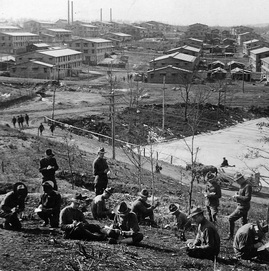

Camp Devens Barracks, 1917 [From here]

|

Influenza Pandemic Kills Many at Camp Devens

From September through November 1918, influenza and pneumonia sickened 20% to 40% of U.S. Army and Navy personnel. […] Braisted pinpointed the arrival of the epidemic in the United States to Tuesday, August 27, 1918, at Commonwealth Pier in Boston. Influenza reached civilians in Boston and on September 8 [1918], arrived “completely unheralded” at the Army’s Camp Devens, outside of the city. Within 10 days, the base hospital and regimental infirmaries were overwhelmed with thousands of sick trainees. [From here]

My dear Burt,

It is more than likely that you would be interested in the news of this place […]

Camp Devens is near Boston, and has about 50,000 men, or did have before this epidemic broke loose. It also has the base hospital for the Division of the Northeast. This epidemic started about four weeks ago, and has developed so rapidly that the camp is demoralized and all ordinary work is held up till it has passed. All assemblages of soldiers taboo. These men start with what appears to be an attack of la grippe or influenza, and when brought to the hospital they very rapidly develop the most viscous type of pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission they have the mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis [bluish skin coloring] extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible. One can stand it to see one, two or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies sort of gets on your nerves. We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day. [From here]

Whether or not Earle Hazen caught the influenza at Camp Devens in fall 1918, he served out the war, was discharged in early 1919, I suppose. He lived 41 more years and is buried in New Britain, Connecticut. I visited earlier this year:

Recollections of Earle Hazen from my mother. She sent me this in August after reading:

“Nice remembrance of Earle Hazen. He WAS a Red Sox fan–very devoted. He drove from Plainville to Boston many times to see games. He took me along twice as I was the only granddaughter to show an interest in baseball. He even showed me how to play, teach me the rules, and would pitch balls to me clumsily holding my bat in our back yard. After my grandmother (Catharine Hazen) died, Earle’s sister Mildred moved in with him in the Plainville house. They went to the Red Sox games together. They visited the house several times a month and we all sat around the kitchen table playing gin rummy for pennies or nickels, as I recall. I remember visiting him at work when he worked at the bowling alley in New Britain, which was near St John’s Lutheran Church where my family were members. I remember him as a quiet, reserved guy. One summer he and Mildred took me to Lebanon, NH, to visit my mother’s cousin Louie. I was about 11 or 12 years old. The house was at the top of a steep hill; at the bottom was the Connecticut River. The only thing I didn’t like was he smoked cigars and that made the trip a bit unbearable. [….] [Y]ou may remember that I gave you the medal that he received for serving in the war; a photo of that may be a good addition [to this post]. My mother had given it to me and I wanted to pass it to you. My parents and sisters were on a trip to D.C. (for fun and history) and Ohio (to see relatives–my father’s cousin Dorothy Ramser’s family). In Ohio we got word that Earle had had a stroke and was in the hospital. We cut the trip short and rushed back to Connecticut. BTW and fyi, the New Britain cemetery is Fairview Cemetery.”

Note that the medal (both sides of it) is now included in the post.