I was employed by a think tank for most of 2019.

What is a think tank? Many ask.

I might be able to record some kind of useful insight into the “what a think tank is” question, based on my own experiences this year and by what I know of a few other think tanks I have been able to observe at close quarters in the past few years (sometimes doing some sort of work for them, sometimes just as an observer).

The think tank hired me to do research on Asia; to help with various of their publications and projects, some new and some ongoing, especially Korea-related.

It was a small think tank, not without its problems. I was the most Korea-knowledgeable person there. I was a regular employee, but those of us at low levels were under a contract for a certain period of time.

The best way I figured out for how to describe (to a certain kind of person) what it’s like at a think tank is this: It’s a series of elaborate, somewhat-interrelated, large-scale, long-term graduate school projects. Unlike actual graduate school projects, money flows towards those doing the work.

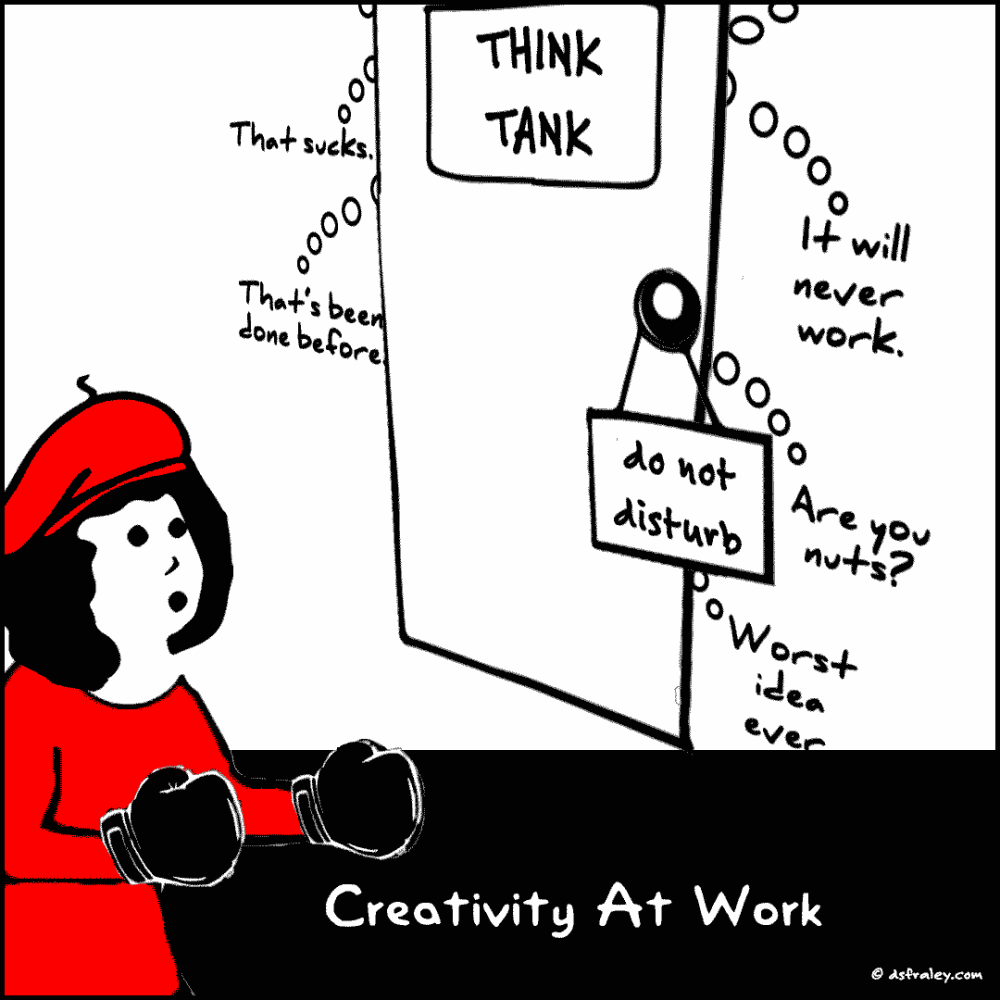

The above sounds good, I expect. On the negative side, most think tanks are quasi-academic and therefore remain always at risk of falling into the same kind of “jealous guarding of little fiefdoms” problem so often observed in academia. Needless to say, this can sometimes create a negative environment.

Another useful way to conceive of this negative side may be: The think tank as a “team version” of graduate school. For many, graduate school itself is, at least intellectually speaking, an intensely personal experience in which you usually have full creative control over your own work, and in which collaboration, to the extent it meaningfully occurs, is voluntary and limited. I would imagine it would be unbearable, for many people who end up in graduate school, if every assignment they did were decided by committee, with the “committee” being several other, let’s say randomly selected, graduate-student-personalities.

Another complication is the competing ‘layers’ of authority:

There is a layer of nominal, hierarchical authority assigned to some of the “students,” against the natural hierarchy of which “student(s)” know more about a given subject: Not who is smarter (whatever that means in this case), but having more experience and/or specific skills or knowledge of a certain area. (When one thinks about it, the latter is exactly why a person gets hired in the first place.)

It all sounds like one of those disturbing 1960s- or 1970s-era social experiments, and not without reason. After work and even at lunch breaks on more than a few occasions, I found myself finding solace by reading Internet articles on good management vs. poor management (always while outside the office).

I wouldn’t claim any of the above is unique to this/a think tank. But because a think tank isn’t producing widgets and distributing them for sale, all these things are attenuated.

— — —

Who pays for all the thinking?

I figured out, after a while, that (1) this is a serious concern for think tanks, leading to huge amounts of man-hours, energy, and resources funneled towards constant fund-raising or trying to secure new projects, and (2) funding is often project-based, which is a major reason why so many employees are on contracts, not permanent.

The overall funding picture tends to be a mix of permanent donors, corporate sponsors, and (indirect or direct) government money, with the latter sometimes foreign as well as domestic.

— — —

Now for the more controversial comments I have on this subject.

Many who have some awareness of “what think tanks are” also have the idea that there is a substantial overlap between think tanks and political power. My observation is, generally speaking, they are not wrong about that.

Think tanks, collectively, do have real, actual, ongoing power. It’s no exaggeration to say some of the big think tank players have more global-scale influence, one might say ‘power,’ than (quite) many UN-recognized sovereign states.

Other think tanks are rallying points for potential power, as in the famous case of the neoconservative Project for a New American Century (PNAC) think tank. That one was founded in the mid or late 1990s and essentially took control of U.S. foreign policy in 2001. The series of US military interventions and near-interventions in the broader Mideast, since that time, trace back to this PNAC takeover. The people who were at the levers of foreign policy making and agenda setting didn’t fall from the sky or happen to all start in government at the same time by coincidence; they were organized, and ready to strike, and did strike. That’s another story.

I see three ways of conceiving of what think tanks are, all of which have at least some validity.

(1) The think tank as purist, independent research institution that studies similar things to what academics do and governments do, but is free of both, not hamstrung by a party-line as an actual government is; in many cases, this can mean a middle position between the two, an intermediary. At their best, they theoretically allow for the creation of real value and insight and lessen the government-groupthink problem. At their worst, they combine the worst traits of both academia and government: They can be subject to the “fiefdom”-ism trap of their own, navel gaze, and nestle their bloated bodies into a warm echo-chamber.

(2) The think tank as parallel government — precisely stated, a given think tank as a little sliver of a parallel government, since no think tank specializes in every aspect of everything. Conceived this way, the work they produce is secondary in importance than the their real function, which is to “keep the army in the field,” coherent and organized, to await the opportunity to get (back) into the inner circle of the royal court. The think tank as a place for top people to wait around until conditions change and they can get back in. This use of think tanks dates to the 1960s and 1970s. Zbigniew Brzezinski and Henry Kissinger were both individual cases of this. The case of PNAC, aforementioned, is a a kind of mob-based manifestation.

(3) The think tank as part of the permanent state apparatus, or better termed in this case, part of the regime, not the administration — (2), above, would be something more like “the administration;” while (3) would be “the regime.” With political and government money sloshing around these places, the lines are blurry, no matter which way you look at it.

A high-prestige, longstanding, well-funded think tank that maintains extensive ties to past, current, and future government officials and institutions is most characteristic here. (High-ranking ex-officials can, and do, fall back on cushy, think tank sinecures when their time in government is up.) This kind of think tank, at its worst, is like a paramilitary force acting on behalf of the ‘regime,’ but which the regime can wash its hands of.

(3a.) It may be useful to distinguish a sub-type of (3): think tanks funded by and/or operating on behalf of foreign powers. They may or may not become registered foreign agents, but their legal status is secondary: They are, at their worst [?] (or possibly, by definition) extensions of the power of a foreign state apparatus or a foreign, para-state actor.

Most foreign powers aren’t ham-fisted enough to directly control what their on-the-ground think tanks based in Washington or elsewhere do, day-to-day. The (few) people I know working at such places all say they are given a free hand. Still, the foreign sponsor(s) can occasionally make power plays, and even pull funding entirely and kill off their “own” Washington-based think tank, even overnight, in the event of a rift. (I saw exactly this happen, at close quarters, in 2018.)

A think tank can be any combination of the above 3.5 “types,” or some degree of all at the same time.

A person, an individual, who floats into the think tank world will also fit, roughly, into one of these 3.5 types, in terms of their temperament or motivation. I certainly place myself in category (1). I had a front-row seat in observing a (3a.) think tank for two years — this being the same one killed-off in 2018 by a foreign sponsor cutting all funding suddenly following a dispute — and seeing the way they operated bothered me in many ways, as I know it bothered other Americans who were able to observe it.

There are certainly many people attracted to, motivated by, (2) or (3) — a (2) person might be a highly motivated ideologue, of some kind, in their area, while a (3) person might be that type recognizable, no doubt, in all times and places, back it must be to the ancient Sumerians and further back still, and through the present day: The person attracted to power for its own sake and who seeks to be around it. Like the mosquito is to light, some just find themselves drawn in and and cannot seem to fly off; it’s light, the mosquito reasons, how can one not go towards it?

Criticizing a think tank, or think tanks in general, on (2) or (3) terms is something seldom done in polite company, I think, because it’s rather close to home; criticizing on (3a.) terms, foreign funders, is lower-hanging fruit.

Every think tank likes to keep the veneer, in public and officially, that they are solely a (1)-style institution, and of the positive kind at that (productive work done at an honest pace; work produced for a wide audience and not a small echo chamber; little or none of the energy-sapping, internal “fiefdom”-ism problem). It seems to me very few meet such a high standard.

— — —