For thirty-six hours, as of this writing, Germany has been in uproar over something in Erfurt, the capital of Thüringen, a state in Germany. It was an election. Ninety assembled delegates, popularly elected late last year, assembled to choose the new head of the state government. Once elected, the head of the sttae government (Minister-President) would appoint cabinet ministers and get on with the business of things.

All the commotion is about the party known as the AfD, which was crucial in electing the winner. It appeared that the AfD would be “in” (though not leading) a state government for the first time ever. The AfD had broken through the cordon sanitaire.

This may not sound like a big deal, but it is, at least in Germany, and I have been seeing it unfold live, if from a distance. I would compare it metaphorically to a case of significant civil unrest, or a war panic. “Constitutional crisis” gets much closer to non-metaphorical accuracy.

By “constitutional crisis” I mean both the formal constitution and the informal one, but moreso the latter. Most countries have a formal, written document called a Constitution but all have at least an informal constitution which includes “norms,” the way things work, the implied and consensus way of things.

An AfD breakthrough and entry into a state govenment shatters through the Federal Republic of Germany’s informal constitutional provision of the “cordon sanitaire” against right-wing political forces to the right of the CDU, which today is a centrist party (and I would propose that seeing the AfD of today is the CDU of the 1980s or 1990s is a useful way to understand it). If that fundamental aspect of cultural-political life slips, it is a crisis for the regime in Berlin. And that explains why so much attention is being funneled on one small state.

I don’t know that this has even made the news in the US. The boring news-fare in the US is the Trump impeachment vote, the “State of the Union” pep rally, Coronavirus, and the Iowa Caucus counting failure. All those are shoving around for elbow-room in the US news-cycle.

Thüringen has so totally dominated the German news the past two days that one has to do some real legwork (or scrolling-work) to find any sorts of other news stories on top news sites. It’s being described with words like “shock,” “earthquake,” and one news outlet even (dishonestly) used the word “coup.”

By coincidence, the US impeachment political-theater ended with the foregone-conclusion acquittal vote the same day as the drama at Erfurt.

I must admit that I found the impeachment intolerably boring and also unnecessary given the foregone-conclusion nature of it all. A waste of time. The Erfurt drama of the past two days, on the other hand, was a genuine drama, a shock development. It seems to have caught people by surprise. I know I didn’t expect it.

What has just happened does seem historic, to me as an observer. Maybe it will be forgotten, maybe not, it’s hard to make calls like this in the moment. I am writing as it is happening, so this is a kind of political diary of a distant but highly interested observer.

In sixteen or so years of following German politics, including a period on the ground there, I don’t know that I have ever seen something like this, something receiving such outsized, blanket media coverage in Germany given the small size of the state involved and the ambiguity of the entire situation.

Thüringen Revisited

About five years ago, I wrote, and posted on these pages, a post I titled “Here Comes Bodo Ramelow.” Bodo has led the government of the German state of Thüringen (or Thuringia in English), capital Erfurt, since late 2014, just over five years. He made some small waves at the time (2014) for leading the first “far left” government in Germany since 1990. Linke is a party that still believes in Marxism, or most of its leadership does, anyway.

Suddenly, today, Bodo is gone. An alternate title to this post would be “There Goes Bodo Ramelow,” to tie up the loose end left hanging on these pages in late 2014 (“Here Comes…”). It’s not that he came or went that is of main interest, though, it’s the ‘how,’ and the reactions to the how, and the precedent of the how. And the “AfD Question.”

Here is Bodo looking confident during the voting on the morning of Feb. 5:

As far I can tell, he has done fine these five years, and is the kind of figure that the east German regime wished it could have evolved into.

But this time Bodo lost.

Here is the Süddeutsche Zeitung reporting on the aftermath:

That headline (“Politisches Beben in Thüringen; Wenn Rechenspiele Realitat werden”) says “Political Earthquake in Thuringia. When Math-Games Become Reality,” a reference to the mathematical fact that Bodo didn’t have the votes and the AfD did, on paper. No one expected the AfD to be decisive in the election of the new government, despite the “math games” suggesting it should be. As for earthquake? Yes it is.

Consoling Bodo on his shock loss is his fellow Linke party figure Susanne Hennig-Wellsow, b.Oct. 1977, of East German upbringing and thus a natural Linke figure. Though on the young side to really be a loyal East German (she only turned twelve during the anti-regime protests that climaxed in the breach of the Berlin Wall on the night of Nov. 9–10, 1989, with the loss of zero lives), her mother was a figure of the East German Interior Ministry and her father rose to the rank of captain (Hauptkommissar) in the East German police (Volkspolizei) (as described in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung during her original rise to prominence in 2014 with Bodo Ramelow). The Hennig family therefore made the best of their lot in East Germany, and Susanne clearly grew up with a nostalgia for that state, one she knew in her 1980s childhood and was replaced by the pessimistic 1990s by her teenage years and early twenties. East Germans went from the winners of the East bloc to the losers of the Federal Republic. One can understand how she feels.

(Die Linke means The Left; the party, in the context of Thuringia and other ex-East German states, is definitely the successor to the Sozialistische Einheitspartei (SED), the ruling party that seemed so in control until about Q3 1989, then very quickly looked ridiculous. The SED-successor party (previously under other names) was getting fairly strong and consistent vote totals by the late 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s in East Germany, suggesting the East German regime had more underlying popular support than our Western version of events has it. The Linke took enough of the vote to get 29 of the 90 seats in Thuringia thirty years after the regime-unraveling period. If there is a fresh election, which as as of this writing is a possibility, it looks set to gain seats.)

Here were the three state-level leaders of the Linke (Susanne Hennig-Wellsow), Greens, and SPD, back in late 2014, confident that their new coalition would be elected and which put Bodo in power for the first time:

If what has happened in Feb. 2020 is indeed the AfD’s breakthrough into the mainstream, a word on how it happened, as I see it, including drawing from personal experience. The two-word summary: Migrant Crsis, fall 2015.

The last of the new elections since the Migrant Crisis that gave birth to the AfD in present form occurred at the end of 2019 in Thuringia.

The AfD confirmed its staying power in three elections in fall 2019: In the states of Brandenburg (taking 23 of 88 seats), Saxony (38 of 119 seats), Thuriginia (22 of 90 seats), 28% of the whole between them, with the best result in Saxony despite a last-minute judicial ruling that due to a filing error, many of the AfD’s candidates were ineligible (when the smoke cleared, this weird judicial ruling cost them a net of one seat, I think, but could have been more). (I recall writing on this topic at the time but not publishing it here due to technical problems I was having with then-bloghost Weebly and giving up.)

Elections in multi-party parliamentary systems take weeks, or sometimes months, to fully sort out, to “form a government” involving several parties. Germany today has a six-party system with no single party likely to reach as much as a full one-third of seats anywhere ant any given time, and so some combination of the six parties (sometimes a seventh at local level) is needed.

The Thuringia vote broke as follows in 2019 (there is a two-tiered voting system but final number of seats are determined by percentage of the popular vote, minus parties that fail to clear the “5%-Hurdle”):

Thuringia State Election Results (2019):

..90 seats: TOTAL in incoming state legislature (Landtag)

– 29 seats: Linke (in this area, primarily a successor of the East German ruling party; the party of incumbent leader Bodo Ramelow);

– 22 seats: Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) (in this region, the AfD is seen as an civic-nationalist paprty with a strong ethnonationalist current, especially as the state party is led by nationalist-oriented figure Björn Höcke, who quit his job as a teacher to crusade against Angela Merkel during the Migrant Crisis);

– 21 seats: Christian Democratic Union (a mix of centrists, some remaining old-line conservatives, Merkel Machine people, and people who vote for them because of intertia);

– 8 seats: Social Democratic Party (SPD) (a party that is historically leftist, more recently center-left, now largely seen as centrist, fading fast after years of being seen as ineffective junior-partners to Merkel, always propping up her coalition);

– 5 seats: Greens (a party with dissident-left origins in the 1980s that by 2020 is the new primary left-wing party at national level; many ideologically committed ex-SPD have gone to the Greens, but in Thuringia I expect as many or more have shifted to Linke);

– 5 seats: Free Democratic Party (FDP) (a market-liberal, or “freemarket” party; under revived leadership of Christian Lindner it has become an important power-player again, and is at the center of the Feb. 2020 government crisis in Thuringia).

There are many to whom the above is a confusing jumble and not interesting at all. If there are any of those who began reading this, they’ve long since stopped reading, so that’s okay. As for me, I find it profoundly interesting: A stable six-party system.

Since high school I have felt the US could do with something like this. It would make democracy more interesting, instead of having two huge parties with internal factions constantly trying to hijack the whole, why not just split the facitons into separate parties that are more ideologically coherent? The key is proportional representation.

The 90 incoming Landtag people took their seats and, by secret ballot, voted for a new state leader, which they call Minister-President. Tradition holds that the largest party gets to have its leader elected Minister-President, but there is no legal requirement for this.

Incumbent Minister-President Bodo Ramelow no longer had the votes:

Linke+SPD+Greens is a continuation of the Ramelow coalition but now only has 42 votes, needing 46.

A coalition of AfD+CDU+FDP makes most sense, from a “solving the equation” perspective, having 48 votes.

Bodo Ramelow (Linke, incumbent), on his best ballot, got 44 votes, suggesting a clean sweep of the Linke, SPD, and Greens and two CDU or FDP ‘defectors.’ Still not enough.

Björn Höcke (AfD) the anti-Merkel insurgent, got 25 votes, suggesting 22 AfD and 3 CDU/FDP votes. In fact those votes were not for him directly but for an independent not even in the Landtag whom the AfD had proposed as a compromise, a man named Christoph Kindervater (b.1977; I cannot confirm that he is, as his name suggests, a father of children). So technically count that as 25 for Kindervater. Either way, far from enough.

Both main candidates having failed, the voting was opened up to others, just as at a US presidential nominating convention when no one quite has enough delegates (“brokered convention”). The other minor parties were now in the spotlight. The FDP played its characteristic role, deciding to enter its man, Thomas Kemmerich, into the race, perhaps not expecting much.

Then the shock: The FDP man won a majority, presumably taking all AfD, CDU ,and FDP votes. No one knew who was voting for whom because it was a secret ballot. The natural coalition wonafter all, but excluded either of its largest factions, and the FDP, a minor party that barely got any seats, was king. A small case of the tail wagging the dog?

Kemmerich was previously an unknown figure, but now the entire political class in Germany, and many observers further afield, knows the name.

Thomas Kemmerich in, Bodo Ramelow out.

Here is how one outlet reported it:

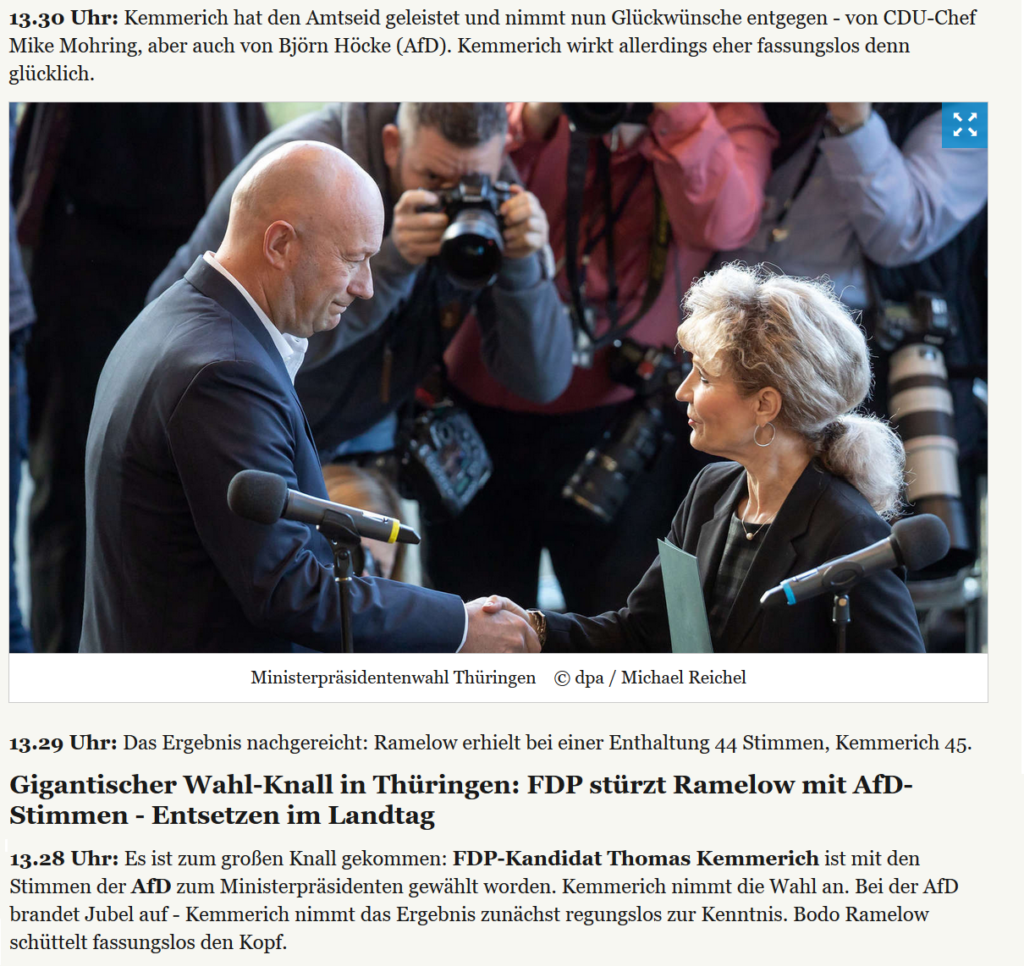

That bold headline says “Gigantic election-shock in Thuringia: FDP ousts Ramelow with AfD votes, a stunned reaction in the Landtag.” I believe this was a live-ticker that was backdated; the live, running updates were added later and the shock-moment of the FDP/AfD breakthrough was back-dated to create a timeline. The crisis began soon thereafter.

The newspaper Welt, which is one I read regularly, has its eight top stories all about the Thuringia Landtag affair as of this evening. That’s eight of eight top stories right now at Welt.de; Seldom is anything so dominant in the news. The other outlets are about the same.

Kemmerich gave his opening speech:

Here is the schoolteacher-turned-political-crusader, AfD figure Björn Höcke, in AfD promotional material produced yesterday, shaking hands with newly elected Minister-President Kemmerich (back turned):

Not long after this congratulation was given came the deluge.

The chattering classes started chattering and twittering about what had just happened.

There is a distinct layer to life in the Federal Republic, as I have observed it, from near and far, of institutionalized opposition to the Right (any part of organized force of any kind to the ‘right’ of the CDU), and formerly to the Left (including but not limited to the party know as the Linke). Political theorists use the term cordon-sanitaire to describe this. A political quarantine, cordoned off from the rest of society. If people inside the quarantine make some kind of organized attempt to break out of a quarantine zone, they are subject to being shot in extreme cases; the political cordon-sanitaire is likewise is policed, and the barriers are regulalry reinforced, and any small-scale breakout is suppressed. This Thuringia case kicked in the professional quarantine enforcers and the volunteer-militia auxiliary into overdrive, red-alert mode.

The AfD is now a voting member of a state government! They began to say, which was based in truth but what exact government Kemmerich would form was still unknown; the histrionics cart had gone way, way in front of the observed-reality horse.

So it was that on Feb. 5 word began to spread that a quarantine breakout had occurred. There were escapees on the loose. They’ll need to be dealt with. The paid professionals and the volunteer militia all began to turn out, and some began to fan out to take up shooting positions (metaphorically).

In the days following the election last year, state-level CDU leader Michael Mohring, whose party had been beaten by the AfD, suggested he’d prefer the left-winger Ramelow to maintain control over any cooperation of any kind with the AfD. This “Better Red than [AfD]” line was not popular with his own voters nor his own party elected officials and there were some signs of a possible mutiny. He quieted down about it, but now I see he has chimed in with a veiled assertion of the same, following the election of Kemmerich. Mohring is a lifetime politician who thought it his due to get the reins of government after all these years he’s been at it.

The FDP national leader Christian Lindner, whom I find to be among the more interesting figures in German politics the past five years, gave a brief press conference in which he disavowed the AfD but said it wasn’t his fault; it was a secret ballot; they didn’t know the AfD would vote for their man; they won’t work with the AfD. This was not entirely convincing, and some have been alleging he masterminded the whole thing. If so, did he miscalculate?

For more than 24 hours, Kemmerich stood firm. The entire ruling apparatus of the German Federal Republic came down on him, but he had been legally elected and saw no reason to apologize.

Top figures in the national-level CDU began a series of ritualistic denunciations. The presumed next chancellor candidate, a woman a hyphenated name so long that people prefer to call her, and she calls herself, AKK, said she would be directing CDU Landtag members in Erfurt to refuse to take any part in a Kemmerich government or face consequences.

To return to the policing the cordon-sanitaire metaphor, longtime insider Angela Merkel herself donned a mask, grabbed a powerful flamethrower, and headed down and join the suppression efforts herself. A breakout discovered in the cordon-sanitaire is serious business, and she was ready to strike. “No cooperation with the Kemmerich government or you’re expelled from the party.”

One wonders if the CDU bigwigs realize they are reelecting Bodo Ramelow, and discrediting themselves in the eyes of many marginal CDU voters. They are effectively vetoing the election results. I don’t know if they possess this self-awareness or not.

Some members of the FDP itself, such as Bundestag member Thomas Sattelberger, grabbed a pitchfork and joined the townspeople heading for the quarantine zone to help the suppression effort. Sattelberger denounced Thomas Kemmerich for “cooperating” with the AfD and threatened to quite the FDP. Once again this Sattelberger is a case of emotional overreaction: Kemmerich did not cooperate, but was elected by secret ballot.

Ask not for whom the lynch mob forms, Thomas Kemmerich, it forms for thee.

There was much less stir, I think, when Linke broke through in 2014. The election of Bodo Ramelow (as written about briefly on these blogpages at the time), who now looks like a fuddy-duddy conservative, did raise right-wing eyebrows but the world did not end. There were no breadlines in Thuringia, no gulags, no huge secret police force that roughed up dissidents (at least not one run by Ramelow), no huge statues of Ramelow or Little Red Ramelow books in schools.

The people with the bullhorn in Germany have begun to call for a new election. Several polls suggest the CDU stands to lose still more seats in Thuringia in such an event. Various other low-level drama was going on, as all eyes were locked onto Erfurt for a second day. There was no other political news. We’ll see what Friday brings.

Now Kemmerich has announced he will resign. The threat from the highest level by the neo-Merkel/wannabe-Merkel known as AKK effectively meant no path forward. Kemmerich was compelled to bow out. Apparently the law says he is eligible for his pay as Minister-President of the state of Thuringia in full, 93,000 Euros, as he was duly elected and legally held the office, despite his resignation. 93,000 Euros for one day’s work is pretty good.

What will come of this?

A new election could mean the CDU loses a net of about three seats and the SPD could lose a net loss of about two; Linke would gain a net of about three. This according to two opinion polls, one from January, one from today.

The Linke party, from my experience, is the conservative option for east-Germans born between about the late 1930s and the early 1970s, those who grew up with the communist regime; if this polling is right, some are shifting back to the known-quantity, safe option.

But these small seat shifts from a new election may mean no change in potential government formation.

The biggest loser is definitely looking like the CDU, both in micro terms (in the state itself with this specific chess game at the Landtag), in state terms, and nationally in terms of prestige. It looks like this affair is discrediting the CDU in the eyes of many of its core constituency, and the AfD stands to gain.

The last word I see is that the state-level CDU, realizing it stands to lose most, is resistant to the call for new election but is in the process of being overruled by the CDU apparatus from Berlin.

An aside.

On the origins of the AfD: The Migrant Crisis of 2015–2016.

As I write elsewhere above this long, reflective political essay, there are a lot of knee-jerk anti-AfD people in Germany, and indeed the entire establishment is counted among them; a distant observer, say a Korean, would probably be puzzled at this.

Seldom will people ask why did the AfD emerge; how has it remained strong; where did the AfD come from.

I see the answer to the question of the AfD’s origins as unambiguous and able to be dated pretty precisely, which I want to relate here by way of memories and personal experience.

Something big, very big, happened in European politics in 2015, and its epicenter was in Germany. It was then commonly called the Migrant Crisis, a bizarre period of huge upsurge in inflow of people, mainly Muslim men, seemingly encouraged by Chancellor Angela Merkel who seemed to invite one and all. She gave orders to keep the border open to refugees who were moving across Europe and kept saying there was “no limit” to the numbers of refugees Germany was willing to wave in from the Mideast, or wherever.

The hundreds of thousands arriving per month, each new wave encouraging the next, so shocked Europeans (and Americans at the time, contributing to Donald Trump momentum during the 2015-16 Republican primary season in the US), that the latter half of the 2010s can only be remembered as the half-decade of successes for what was, at the time, primarily called Populism. I’m not sure the label Populism will survive as a descriptor because it is so vague. But whatever label one chooses, this was a big deal. Brexit rode the same wave of enthusiasm and I am convinced would not have succeeded without the Merkel order on refugees. The Brexit vote was right at the tail end of the so-called Migrant Crisis.

I passed through Germany in Jan. 2017, spending several days in Frankfurt, and saw signs all around of this ‘hit’ that had just occurred. I encountered several men who identified themselves as Syrians aggressively begging here or there, often at train stations, and in English. I recall now one in particular. He was as aggressive as the others, but was bold enough to actually physically make contact with people to get their attention, touching their shoulders or so. Then he half-menacingly said he was a Syrian and went into a canned line about needing food, by which he meant money. It was all with a menacing air, the same kind of opening an armed robber often uses. Needless to say, a disturbing development.

(Other relevant memories from Frankfurt: Lots of political graffiti, much of it against ‘Nazis.’ A church that had been converted into a refugee assistance center.)

On the margins of the news out of Germany since late 2015, we read of refugees involved in robberies, other petty crime and drugs, streetfighting, woundings, rapes, and even murders. A few cases of terorr attacks, the biggest one at that Christmas Market in which a driver raced through plowing into dozens, killing many.

One notable incident was at Chemnitz in Aug. 2018, in which a group of Muslim refugees in their early 20s, apparently all of them among the group waved-in by Merkel, killed a local man and hospitalized two others in a knife attack. Initial reports had the Muslim refugees, who were of Middle Eastern origin, attempting a sexual assault, and that the three German men may have been attempting to stop it; in the media storm that followed, it is hard to sort out what the truth was, but what is known is than that one German man was dead and two were in the hospital in serious condition.

The Chemnitz attack itself was minor, but the outrage somehow proliferated and a large-turnout protest was quickly assembled. Opponents of the protestors claim it was a riot. Chemnitz made headlines for this “right-wing” riot and the usual people lined up to denounce racism as stories spread of the protestors “chasing racial foreigners out of the town” or forcing them hiding. Many of the Chemnitz marchers did say they want no Muslim refugees, want them all out, to return the city to normal. I remember this firestorm at the time. It spilled over into international media. Little was said about the three knife victims or the supposed attempted rape(s) that triggered the protest; little condemnation for the swaggering refugees armed with knives who killed a man.

In looking up this story again 17 months later, I see everyone saying there was no sexual assault involved, just the one murder and two malicious woundings of unclear motivation. The big-boys in the media are all saying the reports of sexual assault were only a rumor. I have no special knowledge here. I do find an investigative report published in a feminist magazine called EMMA (active since 1977) which had a reporter do a series of street interviews in Chemnitz at the time of the controversy. One Chemnitz high school teacher, female, told EMMA that she knew some of the knife-gang refugees, whose identities were locally known in town after the murder; this teacher said the refugees had been known to regularly harass her students, she specified it was at least one of the exact refugees involved in the knife attack. She one of her students was even nearly raped by this same group. Chemnitz is not that big, and these young men were already notorious locally by summer 2018. The report in EMMA was published Aug. 31, 2018.

Images of piranhas released in a fish tank come to mind.

I had been to Chemnitz, once, in 2007. I don’t recall much, but there was a giant statue of Karl Marx’s head, after the former name of the city. The US phrase Rust Belt came to mind for Chemnitz. No foreigners at that time, at least none conspicuous. I was only passing through. Having a spare week, I was headed south of Chemnitz towards the Czech border where there was good hiking, the Erzgebirge. I was on foot. I hadn’t thought much more about Chemnitz between then and Aug. 2018 when it hit the news again.

The Chemnitz man killed in the knife attack in Aug. 2018 was in his early 30s at t he time, just a little older than I.

I recall being saddened and angry, and I am sad now recalling this and other incidents like it. What is one to think? Here is one thing one might think:

Why had Merkel done this?

A lot of people were asking why. It may seem simplistic to believe, but later investigation and reporting revealed that it really was entirely Merkel who made an executive decision to open the border and invite in Muslim refugees “without limit;” she consulted no other senior government official and brooked no dissdnet. She was on a moral crusade.

Merkel showing off how moral she was in this manner got many Germans angrier and angrier,and the anti-Merkel protests whose main slogan was “Merkel Must Go” were marked also by calls for her to be tried for treason.

Merkel was restrained in the end, and the huge inflow of male Muslim refugees dropped to a lower level, though quite a large number had made it in. The spigot turned off after a lavish payoff to Turkey was arranged.

I don’t think it’s hard to imagine what people on the receiving end felt about this. Such a large scale operation looked a lot like a tag-team in operation. It was the sudden perception of the tag-team, all at once by millions, that gave birth to the dissident AfD.

Half of the tag-team is personified by that aggressive Syrian at the train station in Frankfurt I witnessed and mention above (and, maybe in a darker sense, by the knife-armed refugees at Chemnitz, though many would object that very few refugees actually commit murders). The other half of the tag-team is personified by Do-Gooder Merkel herself. The tag-team aspect here was that the latter kept waving-in the former, and the former would support the latter and be useful props in the latter’s quest for world popularity. The latter also holds the bully pulpit and had the power to punish critics. The tag-team is not necessarily brand-new, but the huge scale during 2015-2016 was impossible to ignore. As thousands came in every day for month after month, it left a huge, disgruntled, and ever-angrier constituency in the middle.

The political consequence was that about one-third of Merkel’s own party defected to the new AfD between the end of 2015 and 2017 and millions of disgruntled nonvoters or minor-party voters were mobilized. The AfD was the foremost political voice calling for a strict limit on refugees and the repatriation of those who had arrived and been waved-in; elements of the non-Merkel CDU and FDP also called for the same, but could not outflank the AfD.

Merkel’s Do-Gooderism was therefore just enough to cause a serious rupture in German politics. Germany, being a country with a mature, stable party system and which was in a time of economic prosperity, it would be like, in US terms, if the Republican Party lost a third of its members in the late 1990s to the Reform Party, never to return.

Given the AfD’s dissident right-wing and ethnonationalist tendencies, it occupies exactly the kind of place in politics and culture that the German ruling apparatus (state; media; academia, the big church bodies; really all of mainstream culture) love to bash, and from which bashing it gains a form of what political-science people call negative legitimacy (= They’re bad; we’re not them; we’re against them; so you have to support us.)

By 2017, the AfD was seriously competitive and all signs pointed to staying power. In Sept. 2017, they took 94 seats in the Bundestag (13.5% of total), to a net loss of 105 seats by the CDU-SPD ruling coalition. They have now taken seats in every state legislature, and are the largest party in the former eastern states. Following its unlikely rise in the late 2010s, it is now set to cause real disruption in the 2020s, and the second month of the decade, it had already begun.

(End.)

Updates as of Feb. 7 early evening Germany time, day three of the crisis.

1.) The national CDU continued to push for a new election;

2.) Lots of confusion. The state party is said to have refused the new election, a mutiny;

3.) An emergency meeting was held. Mike Mohring was voted out as CDU head in Thuringia by his own party members.

4.) The CDU national party backed down from its call for new elections. No one knows what’s going on.

5.) A new poll (n=1000 in Thuringia, specially commissioned and conducted entirely on Feb. 6) finds the CDU support in Thuringia has cratered (it took 22% of the actual vote last year –> 12% expected vote in a fresh election), with Linke the main beneficiary (31% –> 37%), exactly as I predict above. The SPD and Greens stand to gain a seat each.

6.) If the new poll is accurate, Bodo Ramelow is back, leading the strongest Linke government ever (if a new election is held, when smoke clears it could be his Linke party at a dominant 40%+ of seats, easily forming a majority with minor support from SPD and Greens). A dominant reformed-SED with minor Social Democrat and Green support is exactly what the East German regime wished it could have transitioned to.

7.) The so-called villainous AfD has had its support remain firm in the new poll. These people surely resent all this fuss and want only to be respected.

8.) Lindner remains at the head of the FDP, easily surviving a confidence vote.

9.) Now late word comes out that the CDU in Thuringia will back Bodo’s return to power. If this was a Prisoner’s Dilemma, the CDU center finally broke and defected to the left, under great pressure from above.

10.) People are starting to grumble about why the CDU did this; they look bad, if not quite Banana Republic-level then something on the way. Why, the grumblers ask, had they voted for the conservative CDU at all, if the latter were just going to fold it up and hand the key to the far-left? (See also point 5).

11.) Kemmerich himself, widely reported to have resigned under pressure Feb. 6, came roaring back in the game Feb. 7 and said he would not resign at this time after all, and would need to be voted out.

The headlines continue to be dominated by Thuringia.

Some commentators are comparing this “east” German election to an “East” German election whereby the results were not correct so have to be adjusted to make sure the proper man stays in power. East Germany did have elections but their results were not competitive. “What is the difference here?”

Update as of evening (Germany time) Feb. 10.

Grumbling continues and political attention remains focused on Thuringia, now five days after the shock.

The head of the CDU, AKK (full name: Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer), up until now the designated Merkel successor, has now resigned as “Chancellor candidate” over the Thuringia fiasco. This was a surprise move. It’s unclear who will be the designated Chancellor candidate for the CDU in 2021 when Merkel finally steps down.

The CDU has seen its support in two new polls in Thuringia drop like a rock, with an overall shift of -8 away from the CDU (from its already low level) and +7 to Linke, and everyone else pretty steady. This vote-preference flux again proves my analysis correct, that eastern Germans born before the mid-1970s will tend to go towards Linke as the conservative option. “Conservative,” conceptually, is always relative.

Now they have been forced to issue another muddled statement saying they will never vote for Bodo Ramelow and prop up a Linke government, nor will they ever vote for AfD. This leaves no majority government possible.

In the event of a new election, AfD will control twice the number of seats in Thuringia as CDU, so they are now hardly in any place to issue threats. The national CDU has taken over the matter, though, and is panicked. This all represents the disgruntled feeling people have towards the party as it exists today.

When the smoke clears after a new election, one plausible scenario has Linke controlling as many as 41 of 90 seats, easily able to form a government with SPD, which will have perhaps 10 seats.

It occurs to me again that this is exactly the Socialist Unity Party’s best-case scenario, and no doubt one talked about in party circles in East Berlin in late 1989 and early 1990 as an ideal. If it could have pulled it off without being annexed by West Germany and mighty NATO, which is highly questionable. A transition of the East German regime to democratic elections with the regime and ruling party surviving intact and at the helm? Impossible, many would have said. Never rush to judgment. Thirty years later and here we are.

(There are implications here for the Korean Workers Party and North Korea, and I am sure they are watching.)

Feb. 11, as of early evening Germany time. The developments as I understand them.

The withdrawal of Chancellor-successor-designate AKK remains the talk of the nation. Successor-talk is ramping up.

Once scenario I recall had AKK taking over from Merkel as Chancellor already in 2020, ahead of the next election (set by law to be “by or before” Sept. 2021). This early succession is suddenly not to be, defeated by an AfD insurgency in the provinces.

Disrupting the CDU and forcing it away from Merkel is an unmitigated success for the AfD, considering the political-cultural lay of the land in today’s Germany, which as I tried to described in this post is as hostile as can possibly be to a party like the AfD. (AfD activists are subject to considerable intelligence-service surveillance and whenever possible are charged with crimes, including speech-crimes; one AfD supporter with 250k subscribers on Youtube is due in court next week for allegedly insulting a Muslim lawmaker in Berlin.)

And so it happened that the AfD has achieved its main goal when it ramped up in fall 2015. The ex-CDU man Gauland, who defected to the AfD and became a co-leader, defined the AfD’s goals simply as: “Wir werden Frau Merkel jagen,” which can translate to “We’re on the hunt for Frau Merkel.” (Jagen means hunting, as in animals; I’d propose a better translation as “We’re coming for you, Frau Merkel.”)

_______________________

The most likely new CDU candidates for Chancellor are:

The five plausible candidates, in rough order of pro-Merkelism to anti-Merkelism (ideologically ‘left’ to ‘right’):

Laschet; Kretschmer; Merz; Spahn; Söder.

The front runners are Laschet, Merz, and Söder.

Chances are good that one of the above will be German chancellor, maybe still on the Q3Q4-2020-handover timetable, or maybe not until late 2021 with the fresh election, and then only if the CDU “wins” and can form a ruling coalition.

In any case, all five are men. The high-brow, left-wing Spiegel ran a jokey headline, “Is Germany Ready for a Male Chancellor?”

(Merkel’s chancellorship began in late 2005 and desginated-successor Frau AKK’s expected chancellorship was to be least some of the 2020s.)

Laschet (b.1961; Catholic; Aachen origin; three children) is being called “the male Merkel.” The most left-leaning of the three front-runners. If he becomes the CDU’s Chancellor candidate, the CDU will be confirmed to no longer be, in any real sense, of the Right. The problems of the late Merkel era will continue. Easy fuel for the AfD’s fires.

Then there is Merz (b.1955; Catholic; Rhineland ‘patrician’ origin; three children), a longtime political figure. He is “in the middle” by default among the three being talked about as front-runners. In US terms, we can compare him to Joe Biden in the US Democratic nomination race in 2019 – 2020 on: longevity of political career, decades-long insider status, unremarkable middle-road-guy-ism. Seemingly Merz is th econsensus candidate to prevent further conservative defections from the CDU.

Finally, the conservative Söder (b.1967; Lutheran; Nuremberg origin; four children) is a conservative with populist-nationalist sympathies. Had he not inherited control of the CSU in Bavaria in 2017, he would have seriously considered defecting to the AfD, with much of the rest of the CDU, in the late-2015-to-2017 period. I think he is one of those who put or (at least appeared to be putting) pressure on Merkel from the right that caused her to reluctantly end her Muslim Migrant Open-Door Policy by Q2 2016 and not bring it back it in 2017 or later. The “Merkel migrant crisis” was a profound, one-time demographic shock in Germany and likewise shocked European politics, giving birth to the AfD as a desperate nationalist opposition; it never would have happened as it did had Söder been in. Still, Söder is a party-machine person and not a self-conscious insurgent as all the heads of the AfD are.

That takes care of the three front-runners, from left-most to right-most. There are two other possible candidates: Spahn and Kretschmer.

The youngest candidate Spahn (b.1980; another Catholic, Westphalian origin), like Söder a consistent critic of the Merkel Migrant policy. The surprising thing here, maybe, is that Spahn is Gay and married to a man. He is also a lifelong political figure, with a major rank in the CDU youth wing already by the end of the 1990s and in the Bundestag from 2002. A formal-politics ‘lifer.’ So involved was he that he only finally took university degrees at age 28 (BA) and 37 (MA). Both in political science, naturally.

Last is Kretschmer (b.1975; East German origin and upbringing; Lutheran; two sons). I have interest in this man for a very specific reason: Kretschmer (appearing in spelling variants Kretchmer, Kretchmar, Kretzschmar) is one my mother’s ancestral surnames. Her great-grandmother was born a Kretchmar in Saxony in the third quarter of the 19th century, also Lutheran. (Saxony had a very large Lutheran majority since the era of the Wittenberg revolt.)

As for the present-day politician Kretschmer, he has distinguished himself by following the diktats of the national party in refusing to cooperate with the AfD, which is strongest in Saxony. As of Sept. 2019, the AfD controls a full one-third of the seats in the Saxony state government (Landtag). Kretschmer, the head of the Saxony state government, refuses to work with the AfD, making him another enforcer of the old cordon-santiatre. He goes out of his way to regularly denounce the AfD. I would explain this in part by saying that he owes too much to the CDU as a party-apparatus to do much else.

As an East German teenager, Kretschmer joined the youth wing of the CDU already at the end of 1989, among its first members in Saxony, as the communist regime was suddenly no longer able restrict such political activity after the breach of the Wall. Still in his twenties, in 2002 he entered the Bundestag (along with Spahn), but has been back full-time in Saxony politics since 2017. The reason for the refocus back home? He lost his Bundestag seat, in a direct election to an obscure figure out of the AfD. The AfD now holds the seat in Berlin. A humiliation for the CDU.

In the Sept. 2019 state election, Kretschmer led the Saxony CDU to its worst result locally in post-1990 history (45 seats), and was forced to rule in a shaky and illogical coalition with the SPD and Greens (22 seats combined), just enough to exclude both the AfD (38 seats) and Linke (14 seats; much of previous strength locally lost to AfD). The strange coalition of CDU-SPD-Green holds 67 of 119 seats, and either of the junior partners could derail the government any time if eight of its Landtag members decide to. This is not a good position for the CDU or Kretschmer, its leader, and presaged the Thuringia drama of this past week.

A poll of CDU members was conducted. Who do you want to see as Chancellor candidate for the CDU next year?

Among CDU members born between 1960 and 1990, the age-cohorts seen as the core activist group of the party for the 2020s and 2030s, Laschet has 34% support; Soder, 28%; Merz, 19%; Spahn and Kretschmer each at 4%; all other specific people, <10% combined.

Spahn and Kretschmer do better among other age-groups and regions. Unsurprisingly, Spahn (b.1980) does best among the youngest CDU members (23%). Kretschmer’s strength is that he is the logical choice if the CDU wants to try to take back the east from the AfD. Polls have more East Germans today supporting the AfD than the CDU.

______________________

(Three of the four ‘West German’ candidates are Catholics. AKK is also described as an ‘active’ Catholic, making four of five by that count. Why so many Catholics? What’s going on, one might wonder.

There are multiple layers of identity to every party, which shift over time. An early layer to the CDU, which as a party was only formed in 1949, is the Catholic layer. Germany had just been cut in three large pieces, roughly speaking. Two had very large Protestant majorities, while the third was something close to half-and-half Protestant–Catholic. Moving east to west, the first large piece of Germany was entirely de-Germanized and its people scattered [an Australian I knew in Korea, Elise S., a Lutheran, told me she has ancestral origins several generations ago in this unfortunate portion of the old Germany, and that her parents once made a trip to the ancestral hometown, now no longer in Germany, gravesites untended]; the second piece remained German but became communist; the last piece became a NATO-occupied, partially-sovereign entity called the Federal Republic or West Germany. The first two of the pieces of the old Germany, with their centuries-long, large Protestant majorities, had their cultural-political traditions ruptured by these developments, and had little influence on the new CDU.

The East German regime in the 1950s accused the CDU of being a Washington-Vatican conspiracy against the German nation, reflecting the classic German-Protestant wariness of any hint of political Catholicism. The East Germans’ characterization of the CDU was a lot more accurate than most would probably think today, since the CDU was a partial successor to the Zentrum party, the German Catholic party of the early 20th century that locked-in at times half or more of the votes of all Catholics in Germany. Zentrum has always looked to me like a gang of malcontents nursing and deliberately promoting a sense of grievance alargely on religion lines against the large [Protestant] majority of their nominal nation, and in political terms against Prussia, against Berlin and its the Hohenzollern monarchy and all successors thereof. Chancellor Adenauer was a lifelong Zentrum apparatchik out of the Rhineland and a confirmed anti-Prussian bigot; After Zentrum’s remnants blended into the new CDU with the setting up of the new regime in 1949, he became CDU chancellor.

In any case, this means that a Protestant in West Germany when the new party system emerged was more likely, all else held basically equal, political views held equal, to vote FDP or even SPD, or to not vote, or to vote CDU one day and switch the next, wavering and highly conditional CDU voters, in general a much less stable constituency to draw from. This has, in important ways, continued to the present, even if on the surface religion seems so much less important.

Thinking about the CDU’s ultimate origin, their zeal even in the present day for enforcing the cordon-sanitaire against any even moderate populist-nationalist force is not as hard to understand.

There has been flux in the party system, especially in the 2010s with the decline of both the SPD and CDU, but these are the historical influences and explain why so many top CDU people are Catholics. I would propose that the rise of the AfD in the late 2010s is in part the correction of this long-term misalignment of Catholics disproportionately controlling the main party of the ‘right.’ This was a domestic political situation that was long enforced by the NATO bayonet, even if not consciously or deliberately.)

Update, as of Feb. 18, evening Germany time.

Bodo Ramelow has proposed a unity government to be headed by Christine Lieberknecht, a CDU politician and former Minister-President of the state (2009-2014).

The deal would be: the CDU gets the Minister-President slot and a few minor ministerial positions; all parties except the AfD get real roles in government. This is a bold play and seems likely to work, but it does not look good for the CDU.

Ramelow’s proposed consensus-candidate, Lieberknecht (which means Dear Servant), is not even in the Landtag anymore.

Christine Lieberknecht is b.1958, the daughter of a Lutheran pastor active in the area around Weimar during the communist era. Unlike Merkel’s father who was also a Lutheran pastor (and was called in his time The Red Pastor for left-wing beliefs and for ‘defecting’ to East Germany), Lieberknecht herself grew up a kind of conservative-religious dissident and by her own free will limited her own advancement opportunities by not taking part in communist youth groups (of which Merkel was an active member). With the church in East Germany opening the way to women pastors in her time, she became one, active from 1984 to 1990, and married another Lutheran pastor; they have two sons.

Had the East German regime survived, she probably would have stayed non-political, but her ‘political’ fortunes turned with the fall of the regime. The movement that brought down the regime in the way it went down was, in no small part, famously led by the same conservative-religious-dissident faction to which she and her family belonged (the church-organized marches beginning in Leipzig). This political energy, long dormant, was soon absorbed into the West German CDU after early attempts at creating a separate political party.

Lieberknecht’s first real political act was co-writing and signing a letter dated Sept. 10, 1989, with four other church leaders in Weimar, calling for the withdrawal of support from the East Berlin regime. The movement was just beginning. She was therefore positioned perfectly to scoop up the benefits of 1989, and became a Thuringia Landtag member by 1991, and her prestige allowed her several early state positions, finally rising to the highest position, Minister-President, in late 2009. She retired from the Landtag in 2019.

Bodo Ramelow’s gambit to create a huge anti-AfD unity government that incorporates his Linke party ruling in coalition with the CDU and FDP would itself be a kind of unsung political revolution for the reasons I write about above in this now very long series of observations and political and historical tangents.

Bodo’s proposed coalition is:

Thuringia Landtag: 90 seats total

— Linke: 29 seats

— CDU: 21 seats (offered head of the state government)

— SPD: 8 seats

— Greens: 5 seats

— FDP: 5 seats

= New government coalition (all parties excerpt AfD [22 seats]): 68 seats, 75% of seats.

This seems like a likely scenario now, and the CDU would be foolish not to take it, from a purely immediate-self-interest standpoint, because they stand to lose half their seats in fresh election in spring 2020.

I am also sure, and I have seen some signs of this in news coverage, that some of the key 21 CDUers (those holding Landtag seats and thus votes for Minister-President) would be personally morally opposed to this deal and could even defect and leave the party. But all Bodo needs is just 46 of the 90 votes. For all Bodo Ramelow and the others care, most of the CDU representatives could defect, as long as at least four vote for the new government, he’s got his working majority.

Thuringia remains the flashpoint and the shock waves have not abated. It’s totally unclear who will lead the CDU and be its Kanzlerkandidat in 2021.

The latest candidate is Norbert Röttgen, announced yesterday. He is a longtime CDU figure and chairman of the Bundestag’s Foreign Affairs Committee (Auswärtige Ausschuss).

Röttgen in brief: b.1965; Rhineland origin; another Catholic; a CDU ‘lifer,’ having joined the party in 1982, active as head of the NorthRhine-Westfalia youth wing of the CDU in the 1990s (an important and serious organization in Germany oriented to under-35s; it often gets serious attention, unlike whatever the equivalent might be in the US, which I seldom see mentioned and never see taken seriously), during which time he was first elected to the Bundestag, holding a seat there from 1994 to present.

In the 2000s he rose to first-tier roles in his state’s politics and second-tier roles in the national CDU, as of 2014 chaired the Bundestag’s Foreign Affairs Committee. In the Foreign Affairs Committee he looks to have lobbied for a more independent and assertive role for Germany, and for the EU (though his role doesn’t set the policy). It is unclear if the EU can ever get out from under the parallel security layer that is NATO, and thus out from under US influence and (what many would see as) defacto control of its foreign policy. Röttgen is not foolish enough to say this is the idea too directly, but it seems it is likely the idea.

On the ideological sliding 1-to-10 scale within the CDU proposed above, with Merkel at 0 and the right-most in the CDU at 10 (with those former-CDUers defecting to the AfD mainly being drawn from, say, 7 to 15 on the ten-point scale), I think this new guy Röttgen is at 5 or 6, if the the establishment guy “Mini Merkel” Laschet is at 1 and Söder is at 9 on the pro-to-anti-Merkelism scale, as proposed above.

Single sliding scales are never necessarily useful, though, as they eliminate nuance, such as Röttgen’s stated foreign policy preferences.

This makes six plausible candidates now, and other possible dark-horses in the wings, but I am skeptical that any can turn around the CDU’s fortunes.

__________________

The co-head of the AfD, Gauland, a 2016 defector from the CDU and anti-Merkel crusader, gave a rousing speech on the floor of the Bundestag on Feb. 13 (by coincidence the 75th anniversary of the bombing of Dresden), in which he slammed the CDU’s interference in Thuringia and said it is quickly becoming mired in Bedeutungslosigkeit, or meaninglessness.

Gauland compared the overturning of the Thuringia result to something the Walter Ulbricht would do, the first East German communist leader who once said, “He need to keep it [power] all in our hands, but it has to look democratic,” and compared it to Ministry of State Security (“Stasi”) intervention in West German elections.

Update, as of Feb. 22.

The CDU caves in, will elected Bodo, a historic moment in German politics which was bound to happen sooner or later.

Yesterday, reports began coming out that the CDU of Thuringia, having been strong-armed from above, had now agreed to elect Bodo Ramelow in what they are calling a Unity Government, and (2) for a fresh election to be held in April 2021.

The new minister-president election, in which it has now been announced that Bodo will be elected in a fait accompli, will be held on March 4.

This looks to be an abandonment of the compromise around electing Christine Lieberkencht, who has personally, as of today, endorsed the Ramelow-for-13-more-months-until-new-election solution.

Press reports have the CDU grumbling about this, but as my analysis above has it, all the Ramelow-backers need are four votes from them; their unity now almost totally broken, leaderless at the state level, and under a hostile microscope from above, the wedge-gambit worked.

How did it happen? The sudden turn of events in favor of the Linke, and in favor of the forces that would have the CDU either wedged-apart into meaninglessness a party, may have been propelled by a Feb. 19 mass shooting by a paranoid schizophrenic in a place called Hanau in western Germany, exactly the kind of politicization of a criminal incident one would think one does not want to politicize for fear of encouraging more political-action-through-the-bullet thinking and actions.

The paranoid schizophrenic who did the shooting believed he was being monitored by extra-terrestrials and sinister Earth-based secret agencies who used brain-control devices against him. He shot and killed nine people and then killed himself, also releasing a manifesto to warn others about the secret agencies and the aliens and also satanic rituals and child sacrifice that believed one or both groups were involved in.

The Hanau shooting was a sad, worst-case-scenario outcome for a sick individual who needed help.

But the site of the shooting was a “hookah” bar frequented by Muslim immigrants. Enter German politic sand politicization.

Why he chose that site is unknown, and he didn’t seem to say why he chose that site; his manifesto is said to have been about the secret-agencies that had been terrorizing him for years and stealing some of his best ideas (among other acts, the secret-agency or agencies had manipulated his life to guarantee he had never had a girlfriend by age 43). But because he did choose the hookah bar, the entire weight of the entire system of German culture and politics could not resist the reflexive urge to blame the AfD pretty directly, even if, by the schizophrenic’s own manifesto, race or immigrants or Islam played no major role in his ostensible grievances against the secret-agencies.

I have written on this phenomenon on these pages before. It is one I have long observed in Germany, and I’d like to think I can see what’s going on fairly more clearly than the average, as an outsider. Here was my summary-version, especially as related to the AfD, above:

When something like this happens, they cannot resist starting a mini war panic, and a lot gets lost in translation as the drumbeat goes on.

In practical terms, this UFO- and secret-agency-believer (he also claims the secret agencies had been tormenting him since birth, when an agent of the agencies inserted a device in his brain at the hospital, which he claims in his manifesto to remember happening, on day one of his life) may have one lasting impact, at least; he may have re-elected Bodo Ramelow in Thuringia, and by extension dealt a blow to the CDU nationally, one which I cannot imagine will be easily forgotten in the next 18 months leading up to the next national election.

Update, late evening, Ash Wednesday, Feb. 26 (pre-dawn Feb. 27 Germany time). A few developments, since last writing, that I have noticed and want to record.

________________

Hamburg city council elections. The winner in the Feb. 23 elections for Hamburg city council, as expected, was the Social Democrats (SPD), which will easily be able to form the government again, probably continuing with the Greens.

The Greens sponged-up a lot of centrist voters, the same curious pattern seen across Germany the past two years. The SPD has ceded a lot of voters to the Greens across the board but they are also peeling off some marginal CDU’ers and others. The Greens are the hottest new thing and are now the main left-wing party in Germany. The radicals of yesterday become the centrists of today.

Despite the intense barrage of the anti-AfD media campaign, the AfD held its vote total in Hamburg better than did the CDU or FDP; the FDP lost enough that when the smoke cleared it was a few hundred votes shy of qualifying for seats on the 5%-Hurdle rule (it finished with 4.96%; disqualifying it from seats). The last time the Hamburg city council held an election, it was Feb. 2015, before the AfD really emerged as a strong and here-to-stay party, which definitely dates to Q4-2015 and Q1-2016. So the voting bloc they had five years ago was different than the one they had this time. The AfD’s re-entering the Hamburg city council confirms that the party has cemented its place in German politics. That it can win seats even in such unfavorable territory as Hamburg means it is not going anywhere.

I recall now, in graduate school in about spring 2017, having as a professor a decades-long expert on German politics, who predicted the AfD would soon disappear. He said in effect it would be a coin-flip whether they would even qualify for seats in the Bundestag in the Sept. 2017 election (no seats if under 5%; they ended up with 13%). He misread the situation on the ground. The AfD is still here, and Hamburg shows it.

________________

The CDU Chancellor-candidate race is ongoing.

The candidates I list above, roughly from ‘left’ to ‘right’ and sorted into two tiers on how much support they have, are:

[Left-most]

— Laschet (first tier) [ideol.: Merkelist];

— Kretschmer (second tier);

— Merz (first tier);

— Röttgen (second tier);

— Spahn (second tier) [ideol.: begin the fade into AfD support zone either with Spahn or to Spahn’s right];

— Söder (first tier).

[Right-most]

The CDU has set April 25 as the date it will choose a new party head. All attention in German politics, in coming weeks, will be on this process because there are no other elections going on. The new party head may or may not be the new chancellor-candidate, but the one will at least influence the other.

Spahn drops out, cuts deal with Laschet. In my mini-bio of second-tier candidate Spahn, above (see “The youngest candidate Spahn, b.1980…”), I called him “a formal-politics ‘lifer.’” It now comes out that he has been up to that old politician’s stock-in-trade of backroom deals; he had been in private negotiations with first-tier-candidate Laschet‘s camp over the past week or two. The result is now public:

On Feb. 25, Spahn announced he was dropping out of the Chancellor-candidate race in the CDU deal to back Laschet’s chancellor bid. In exchange, Spahn will get to be “second-in-command” (zweiter starker Mann) and deputy party head; Laschet would be head of the party and chancellor candidate.

Ideologically, this might be a little puzzling, given that Spahn was considered a plausible candidate of the ‘right-wing’ within the CDU, and how the CDU has been hurt so bad by its right-flank being so wide open.

Meanwhile, Laschet, in interviews the past two weeks, has been confirming the validity of his nickname, “the Male Merkel.” He has been saying everything was done right under the Merkel chancellorship and says he would continue on the same course. This deal cut by Spahn, a Merkel critic, on its face seems a cynical political move, but does (alas) greatly boosts Laschet’s chances of being the CDU nominee. Whether he can actually win in 2021 in a general election is another matter.

(Spahn, meanwhile, is busy dealing with the panic around the COVID-19 “coronavirus;” though a lifelong politician by inclination, experience, and profession, his current title [since March 2018] is Federal Health Minister.)

________________

FAZ calls on Söder to not go on “suicide-mission.” The center-right, agenda-setting newspaper, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), published an editorial addressed directly to Söder (who is head of the Bavarian CSU, the “sister-party” of the CDU; and who is, by my analysis above, the most right-leaning of the plausible candidates). FAZ has a distinguished history in the politics of the Federal Republic of Germany. A sign that something had seriously gone wrong was that FAZ broke with Merkel in 2015 over the lighting-rod of Merkel’s Migrant Crisis.

The Merkel-critical FAZ has now called on Söder, another strong Merkel critic, to stand down and not run for chancellor-candidate of the CDU. The surprising thing here is not that it has called for hi to step back but how they did it. It seems they called for him to step back not because they are against him, but because they are for him. From the editorial, “Söder should stay in Bavaria” (Söder muss in Bayern bleiben):

“In a situation as bad as the CDU’s is, for the CSU head to be chancellor-candidate would be a suicide mission.” (Bei einer CDU in diesem Zustand wäre die Kanzlerkandidatur für den CSU-Vorsitzenden ein Himmelfahrtskommando).

The editorial argues that Söder is best able to help the party as head of the Bavarian government, not in a bid for power in Berlin (“Dort [in Bayern] hilft er auch der ganzen Union am meisten“). But saying this in the way they did would appear to mean that the (influential and agenda-setting) center-right FAZ believes that the CDU will not (or, is it should not?) win the 2021 election. Is there any other way to read this? it is truly an amazing thing to have happened, as I expect FAZ has supported every CDU candidate since 1949; formally, they will probably still make the motions of supporting whoever it is in 2021, even Laschet, the Male-Merkel (though if it is him, there is a higher chance they break with the CDU), but it’s clear their heart is not in it.

________________

Historian and commentator Hubertus Knabe publishes analysis remarkably similar to my own. I have made an effort in my life to follow German politics since about the mid-2000s, and while I did live there for a time (less than a year) and have made an effort to learn and keep up with the language to a fairly good level (which this post and series of long comments are partly an exercise in) (I was certified “proficient” in graduate school, if that means anything) (In terms of the news and politics, I can still handle German a lot better than Korean [which has an unfortunate legacy of making anything ‘news’-like be crammed full of obscure Chinese words, among other problems; Korean news-language feels something like the former Western tradition of putting serious writing in Latin], though in conversation I am better at Korean.)

This post and this series of extended comments are running commentary on what I am observing, as a language-capable and informed foreigner who feels some degree of fraternal kinship and cultural ties with Germany. What I’ve written here is not quite what I see in commentaries from anything like the “median German” of today. But that’s expected. There is always a fish-in-the-fishbowl problem. The fish might know the fishbowl really well, but they also cannot see it from the outside. Perspective can yield insight, or allow a freer hand, at least sometimes. Anyway, I am recording my own observations and thoughts in a basically open-journal-like fashion here.

A real expert is Hubertus Knabe. He has just published a 2800-word essay on the Thuringia political crisis, “How Thuringia will change Germany” (“Wie Thüringen Deutschland verändern wird“), dated Feb. 23. I read through it and while Knabe, as a lifelong German (b.1959; East German birth, West German upbringing, family ties to the Green movement in the ’80s; historian), certainly knows more than I do, I patted myself on the back that he came to all the same conclusions I have in this post and comments.

The one-sentence summary of Knabe’s essay on the Thuringia crisis that played out to such high-drama in Feb. 2020: “It accelerates the self-destruction of the Christian Democrats and strengthens a party [Linke] that wants wants change of the entire system in Germany.” (Sie beschleunigt die Selbstzerstörung der Christdemokraten und stärkt eine Partei, die in Deutschland den Systemwechsel will.)

Update, events of the first week of March 2020.

The denouement of the immediate Thuringia crisis. Bodo back in, for thirteen-month interregnum.

As expected, Bodo Ramelow was elected Minister-President for the state of Thuringia on March 4, with the CDU abstaining, as per their agreement.

Scattered grumbling from various corners continued at this spectacle of an election result “overturned.” This event confirmed all the worst of cynicism about German politics that many have had for years.

This is how the March 4 “re-vote” for Minister-President went. Björn Höcke of the AfD got 22 votes, exactly the number of seats the AfD holds, so he has the full confidence of his own side; Bodo Ramelow got 42 votes, exactly the number of Linke+SPD+Green seats; 21 voted ‘Abstain,’ exactly the number of CDU seats, a party now in full disarray. We see therefore very tight discipline, unlike in early February. (It is a case of the kids getting into the cookie jar hile the adults were away, and, when found out, getting scolded severely and hit, then shaping up and on their best behavior while adults were around.)

The FDP (5 seats) did not vote at all in this “re-vote,” neither ‘Yes’ nor ‘No’ nor ‘Abstain’; one of the five of them didn’t even show up. I can only interpret this to be a strong protest from the FDP. If the CDU is in disarray, one wonders what those five FDP’ers must feel — a media firestorm has just cast them all as villains and humiliated them. I would boycott the process too.

In any case, Bodo was in, given that the laws of the Landtag, it turns out, specify the person with the majority of votes cast excluding abstentions wins. The abstention-strategy was a compromise by the CDU to try maintain some dignity of its own and head off the “the CDU voted for a communist” criticism.

A surprising side-development was that the AfD’s Michael Kaufmann (b.1964; East German origin; Protestant; married, two children; an engineer and AfD-Thuringia founding member) was elected Vice President of the Landtag, on a vote of 45 ‘Yes,’ 35 ‘No,’ 9 ‘Abstain,’ and one member not present. This means he got almost all the votes of the AfD, CDU, and FDP.

________________________

US politics takes a similar turn. Biden as Bodo.

In the USA’s Democratic “primary season” (a tiringly long affair and kind of an embarrassment, if you ask me), at about the same time as Bodo was put back in the top spot in Thuringia, all the other main candidates except Bernie Sanders suddenly withdrew in unison and endorsed Biden. Biden had, before this remarkable turn of events, looked pretty mediocre. The move guaranteed that Biden would win and shut out the main rival Sanders. The now-all-but-over long Democratic primary process was wrapped up in a few days with the sudden withdrawal-endorsements.

I’d make a comparison here. The first week of March 2020 in both the US and Germany was one of cordon-sanitaire-enforcement work.

In Germany’s case, the AfD had breached the cordon-sanitaire. The breach was plugged, and things set right, though some damage was done. In the US Democrats’ case, the real threat of Sanders taking the nomination as a left-wing insurgent (as he was in 2016), which was a strong possibility, was ended almost as by fiat. I was following this process reasonably closely (though was annoyed by it; the primaries are a strange process that waste time and energy and are of unclear value). I can say with certainty that none predicted the Biden win, even days before it happened.

A main difference with the Biden Bonanza vs. the Bodo Blitz affairs is procedural. German law allows a do-over, a re-vote. This is what they did. There would be no re-vote if Sanders had won the majority of delegates and had somehow been successfully nominated in the summer. As such, the US Democrats, engaged in an obvious and in-your-face cordon-sanitaire police action, killed off Sanders in early March. (Ironically for this analogy, Bodo and Bernie are close politically.)

_____________________

The Thuringia Crisis at “one month,” and its place in history

As the immediate Thuringia crisis (which began in the first week of February) is now over, maybe this will be the last comment-update I make here. The original post, and my (now) eight comments, are up to 12,000 words of running commentary. I am happy with it, as it constitutes a political-observational diary.

A month on, I still feel that the Thuringia shock was a historic moment, and is among the most significant single moments I have seen in observing German politics since about 2004. The time and energy I have spent on this over the past month, reflected in the quantity of writing here, is testament enough.

The “High Drama in Erfurt” (as the original post here was titled) in early February 2020 was really not a stand-alone, of course. It was part of the broader story of the rise of the AfD that started in Q3 2015 with the “Merkel Migrant Crisis.” Something like this was bound to happen, eventually, and it was bound to happen first in the east. If I had to have guessed, I’d have guessed Saxony, but Thuringia it was.

Thuringia should count as surprising (and one reason it became as big a story as it did) because of how much the Establishment loathes AfD-Thuringia frontman Björn Höcke, even subjecting him to harassment from the domestic intelligence service and leaking their operations against him to the media. A man who leads a political party that controls one-quarter of the seats in a state legislature! This would again be comparable, I think, to a campaign of FBI harassment against Bernie Sanders. It came as no surprise that Bodo refused the customary handshake when offered by Höcke. Video of the handshake refusal circulated widely.

Thuringia is set for fresh elections now, by agreement, in April 2021, just a few months ahead of the expected nationwide general election (probably Sept. 2021). This means Thuringia is going to stay in the news. It will be an important contest next spring that foreshadows the general Bundestag election that fall.

_________________________

Erdogan catapults migrants at the EU

Given a major theme of this running commentary I have done over the past month, this cannot escape mention here:

The Migrant Crisis is back.

Turkey aims to coerce Europe related to its byzantine disputes with Syria and/or Kurds, and has begun the extremely cynical policy of busing-in migrants from the Mideast to the land border with Greece. It would seem a bid to intimidate Europe. These migrants (mainly) want to go to Germany to take advantage of all the free goodies they’ve heard about. So they say in their own testimonials to journalists who have assembled at the Greek border.

This looks like a close repeat of 2015, except with the difference that (1) this time Turkey’s Erdogan is very directly the orchestrater of events, flagrantly reneging on the multi-billion-dollar agreement to help close the border with the EU, having the impudence to bus-in migrants from hundreds of miles away and drop them off at the border, to demand entry into the EU; and (2) Merkel is so badly damaged that it is all-but-impossible to see her ordering an open border for six months or more, like last time, and demanding the EU/Germany take in anyone who calls himself a refugee, “without limit.”

Another difference is how strong a resistance Greece itself is mobilizing. It has strengthened its border defense forces and its Prime Minister has announced that no migrants who storm the border will be allowed in, and for good measure Greece will be ending its asylum program indefinitely until the migrants stop trying to storm the border.

Erdogan is not at all popular in Germany. He seems to think blackmail-via-sending-in-migrants is a winning policy and will definitely cause Europe to fold quickly and give in to his demands. Sadly, I’m not sure that he is wrong, as outrageous as it is to use migrants as ‘weapons’ in this way.

The migrants that Turkey has bused in, again overwhelmingly young males from the looks of it, are now massed at the border and skirmishing with Greek police and border security personnel daily; unclear how many have broken through. A few have tried to land on EU territory by sea, again, and the Greek Coast Guard has been active in refusing the boats. Some reports have the Turkish Coast Guard escorting the migrants’ boats, again a shockingly cynical, quasi-Act of War.

Journalists have shown up, on cue, and in interviews most of these new migrants say they want to go to “Germany,” which again proves my analysis in this running-commentary correct, I would say.

The head of the Greens played to character and issued a call for Germany to airlift-in some of these migrants, which to me is just laughably naive and dangerous talk. I mean, have they learned nothing? Any encouragement of this from the top, like Merkel’s 2015 blunder, is going to (1) encourage a lot more to come, (2) cause serious political seismic waves you cannot predict.

Naturally this was front-page news in Germany, and for a while pushed the sensationalist COVID19 coronavirus coverage off the front pages. It has since competed with the saturation-coverage of the COVID19 virus. On which, by the way…:

____________________

COVID19 coronavirus and Migrant-Politik

In virus-panic news, the Italian media has reported that one of the early infected persons in their large outbreak was a Pakistani migrant, possibly even one of the 2015-16 Merkel Migrants, who was working as delivery guy for a Chinese takeout in Milan. Perhaps it was even untaxed, cash-in-hand work. The delivery guy tested positive and was asked to self-quarantine but ignored the order and continued working for days, zipping all around delivering food which he handled.

Ignoring a quarantine is a serious offense. If you’re used to ignoring social rules, such as by entering Europe illegally and also working illegally for cash-in-hand employers in the first place, you’re less likely to follow a quarantine order.

It seems to me that following quarantine orders in an early outbreak requires reasonably strong social trust. Tossing in migrants who forced their way in and live on the margins (as in this Pakistani doing cash work delivering food for a Chinese takeout in Milan) inevitably reduces social capital. Some would react negatively to this statement, I know. But it seems obvious to me, and so I was not too surprised to hear of the Italian media’s report on this. (Just as I wasn’t surprised to hear that Shinchonji, a religious cult in S.Korea that I grew to fear and intensely dislike from experiences with them. Shinchonji are highly evangelistic, international-focused, and aso deceptive very willing to break social conventions, and distrustful of the government. They were the source of the outbreak in South Korea; there are similarities between their siege mentality and that of an Islamic migrant living on the margins in Europe in the key ways here that would lead to breaking quarantine with impunity.)

The Pakistani migrant who so flagrantly broken quarantine for so long was finally detained by the army; they say he will spend three months in prison for his crime, which is the maximum sentence. Who knows how many of the elderly who have died got it through chains of transmission that he started?

Well-intentioned people, including the head of the German Green Party — who could plausibly be Germany’s next Chancellor, given that her party will probably have the most seats of any party — believe, or want to believe, that there are no real ill effects of scattering thousands and millions of Muslim migrant men in Europe every few years. I know plenty of people like this among the older generation of Western people. I think they believe we are invincible and that charity is limitless. I have never seen it that way myself. Just from a political-analysis point of view, encouraging Islamic and African migrants to come into Europe in force, waving them in (in the terminology I used in the original post here, I think) can cause, has caused, and will cause serious disruptions. With 100% certainty, the Merkel Migrant Crisis caused the AfD to grow into a national party, one competitive with the CDU itself in much of Germany, one that has displaced the CDU in most of the east. The Migrant Crisis of 2015-16 very likely pushed other populist movements in the next few years over the top, including Brexit, and maybe even Trump.

The lesson here is one of microcosm. A mutual-appreciation-society of do-gooder politicians who call for more migrants and refugees so we have show our virtue to the world, these are actually real people. They are not pets. They are real people who will lead real lives, very likely on the margins; social cohesion will go down, and native reaction will go up, especially once the government begins its inevitable policies of setting right the fact that many of these people are “marginalized” by handing them things, free this, free that; the natives’ reaction is going to be, what? I guess you need a team of the best rocket-scientists to figure this puzzle out.

The Pakistani food delivery guy story is just a microcosm, a symbol. In some ways it is a signpost to the AfD story, and to Thuringia story, really, and therefore to German politics as it exists in observable reality in the 2020s.

____________________