The sitting Mayor of Seoul committed suicide in July 2020.

Park Won-soon (elected mayor of Seoul, Oct. 2011; reelected, June 2014 and June 2018)’s suicide triggered an early mayoral election, now set for April 7, 2021. The early phase of the campaign is underway.

The leading candidates in the Seoul mayoral special election are:

- Ahn Chul-Soo (also spelled Ahn Cheol-soo),

- Park Young-Sun, and

- Na Kyung-won.

The first of these, Ahn, is a former software developer, PhD, and professor who spent the 2010s bouncing around politics, and who by now qualifies as a “perennial political candidate,” popping up in races all over. I have a surprisingly long tradition on these pages of writing about him, and he appears as an important feature in Post-66, Post-71, Post-340, Post-342. This post will have the biggest treatment of Ahn Chul-soo yet, and I am writing today with a much more mature understanding (althought still lacking) understanding of Korean politics.

A recent political cartoon of Ahn’s late-December 2020 announcement that he was running for Seoul mayor has him as the champion of the “anti-Moon federation,” trying to see which way the winds are blowing:

Ahn’s competitors are both women: Park Young-sun is of the Establishment-Left (Moon’s) party; Na Kyung-won is of the Establishment-Right party.

___________

This post started as a brief mention of the upcoming 2021 election but has since grown into something more meaningful, correspondingly longer, and more personal. I also meant to write about the 2018 election at the time but never got around to it; it’s good I’m finally getting it done now.

Recorded are thoughts, experiences, and other material on the 2011, 2014, 2018 and 2021 Seoul mayoral elections, during all of which I happen to have been in Korea. There is a mix of personal reminiscence and political analysis/commentary through personal reminiscence, especially on 2018, having dug through old photos, I am posting many of them here. (I’ve come to view the recording of personal reminiscence and thoughts as the purpose of my writing on these digital pages, and those who wish to take the time will find as much below.)

(Original, Jan. 4: 1600 words.)

(Updated: Jan. 5 and Jan. 6; expanded significantly to 7700 words with many pictures and one video taken by me at the time.)

_____________

I start with the immediate past (2018), then circle back to the present (2021), jump back to memories of the more-distant past (2011 and 2014), and finish with thoughts on the future (2022, the next presidential election, of which this special Seoul mayoral election is an important stepping stone).

_____________

The Seoul Mayoral Campaign of 2018

I was in Korea at the time, in June 2018. In the peak-campaign period I was mainly in Seoul itself, and did soomething of an on-the-ground investigation, the results of which I had not compiled and published in disciplined written, until now.

June 2018 was a regularly scheduled election, held the same day as regional elections across the country, including for minor neighborhood offices and city- and state-level positions. There was campaigning everywhere in the usual Korean style with posters, banners, slogans, and sound-trucks.

I believe I was staying near Yongsan at the time, where some of the pictures in this essay were taken. (An ever-present concern of mine in 2018 moving around trying to find deals on yŏgwan (inns) depending on where I needed to be and for how long, a good-enough mode of accommodation at which I was confident none would try to speak to me in English, and at which I knew I could negotiate down the price.) Many others are from Youngdeungpo, where I went because I knew I could find banners out in force there. Others are scattered here and there.

_____________

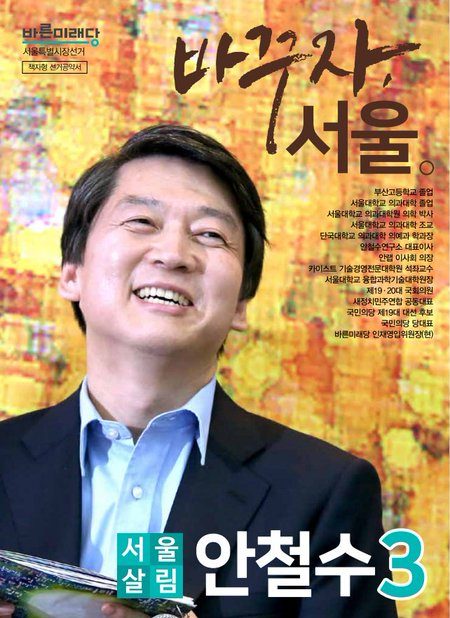

2018: The Main Candidates via their Campaign Posters

The three principal candidates for Seoul Mayor in June 2018, in order, were:

- (1.) Park Won-soon (Establishment-Left),

- (2.) Kim Moon-soo (Establishment-Right), and

- (3.) Ahn Chul-soo (independent, widely known as a Centrist):

As I write from the future, I already know the result:

Park Won-soon wins the election (as expected) but dies by suicide on a mountain in the north of Seoul, two years later. He had been mayor eight years and nine months, and was halfway through his third term, at the time he went missing and his body was discovered.

But there is much of interest in the June 2018 itself, and not just of historical interest, given that present-day politics is generally always a product of past politics and trendlines pushing themselves onwards.

_____________

2018: The “Candidate Numbers”

The big numbers next to the names are “Candidate Numbers.” These are necessary because of: (1) how frequently political parties come and go, often ending up with similar names, and (2) because a lot of people themselves have similar names. They use numbers to help keep things straight.

An example of the former is is the Establishment-Right party’s latest name, the “People Power Party” [국민의힘]. This name is almost identical to a major rival party headed by Ahn Chul-soo (on whom much more coming in this essay), the “People’s Party” [국민의당].

An example of the latter is the so-called Three Kims. In the 1990s there were three powerful political figures who dominated South Korean politics, all surnamed Kim. Some called it the “Three Kims Era.” South Korean media kept it straight by referring to them by their English initials. (The most successful of the Three Kims, Kim Dae-Jung, was usually referred to in writing as “DJ,” dropping the “Kim” entirely. This is long before my time observing Korea even peripherally, and I learned this fact from longtime journalist Donald Kirk’s book about Kim Dae-Jung’s career.)

Also on the need for candidate numbers: In June 2018, a “Park Sun-Young” ran for Seoul Education Minister and nearly won. The April 2021 ruling-party’s candidate for Seoul Mayor is a “Park Young-sun.” So there could well have been a Seoul Mayor Park Young-sun ruling with Park Sun-young as Seoul Education Minister. See what I mean?

___________

2018: “On the Side of the Times”

Park Won-soon‘s 2018 mayoral campaign slogan was “On the side of the times; on the side of the people.”

This choice of words signals, to me, a conscious appeal to the apparent popularity of the Candlelight Movement. I think viewers of this slogan in mid-2018 would recognize it as such. The Candlelight Movement had put President Moon in office the year before, and still retained its mystique in 2018.

Implied is that “the times” of 2017-18 were that they had pulled off another glorious and peaceful revolution, just like in 1987. The latter had, by the 2010s, become a mythologized event and a victorious historical narrative, in which Korean protestors supposedly forced President Chun Doo-hwan to allow for early direct presidential election after years without them. “Get on our side, the side of the winners!” is also an evergreen appeal.

This is the basic narrative of the June 2018 Seou lmayoral election itself. A modified version of the same holds for the June 2014 mayoral election, also won by the doomed Park won-soon, as I’ll comment on more below.

______________

2018: The Campaign Trucks

Looking back into my June 2018 photos, I find this, a campaign truck parked in front of Yongsan Station’s big south-facing plaza with high foot traffic:

It says: “1. Park Won-soon. On the side of the times; on the side of the people. [Smaller, yellow:] Candidate for Seoul Mayor. Democratic Party.” (More comments shortly on what “the side of the times” here specifically implies.)

Here is one the small fleet of converted campaign trucks in use in June 2018:

You can see this mini-truck has been converted to a kind of stage allowing people to stand in the rear, fully visible to the public. There is a screen on this one, and a powerful sound system.

When it is in motion there are often people in the back doing slogans or cheers. Most often this has been a lead man and two attractive women on each flank grinning and waving at bystanders as the truck cruises by at low speed and the sound system blares. Sometimes the candidates themselves are in these converted trucks.

At Hapjeong, near where the Foreigner’s Cemetery is tucked away, I spotted a team of girls hired to campaign for a Chae Woo-jin, candidate “1” for Mapo District local council. The campaigners are identifiable here in blue shirts and caps. I am guessing they were at it all day and here they are resting. (Photo taken June 11, 2018, two days before voting day:)

(Chae Woo-jin [채우진], of the Establishment-Left ruling party, campaigned as a youth candidate and won a majority of the vote in his district. He was only 31 at the time. He might have a future in the National Assembly.)

Here is a campaign truck for the minor-party candidate (Candidate 6) of the left-wing Minjung Party, parked in the Hongik University area, evening June 11 (two days before voting day):

The Establishment-Right’s Kim Moon-soo is seen here campaigning at the bakc of a campaign truck (Internet picture):

The third of the big three was Ahn Chul-soo, whom I later by chance saw o on a street corner, holding a last-minute rally with lackluster success, the night before the elction.

_____________

The 2018 Minor Candidates

Besides the big three, whose rhetoric did not noticeably differ from one to the next, there were six minor candidates, more clearly ideological. They were running to push agendas, hoping to influence the bigger parties. For the first time, there was a candidate basing a campaign around calling herself to be a “feminist” (Shin Ji-hye, Candidate 8), whose campaign seemed to have hijacked the Green Party. Her 2018 mayoral rhetoric is of particular interest because there is almost mothing Green/environmentalist in it, and almost all of it was Feminist.

There were two “hardline right-wingers” among the minor candidates, invigorated by the recent “Candlelight Coup d’Etat” targeting President Park Geun-hye.

Here are some of the posters for most of the ideological minor-parties:

The Korea Patriot Party candidate (above) uses an old slogan from the 20th century, “Marching Against the North and Unify,” and calls for strengthening the alliance with America. She also boasts of her educational achievements and leadership in anti-North-Korea-regime civic groups and that she is a qualified lawyer in Washington, D.C.

There were two other minor candidates besides Numbers 5 to 8:

Candidate 9, Woo In-chol, ran under an “Our Future Party” label. His reason for running was that he was born in 1985 and therefore was to be, he believed, the youngest candidate. (In fact the “Green Feminist,” Candidate 8, turned 28 a week after election day, making her younger by five years). Woo’s top agenda item was that South Korea needed a president under age 40, like France, Greece, New Zealand, and others (and that — hint, hint — he was available and would still be under 40 at the time of the next presidential election, in 2022). I remember seeing public activity by this party. In my brief observation, their outreach reminded by unusually of Korean religious cult activity. But minor parties are possibly always little political cults anyway.

Candidate 10 ran on a platform that tiptoed near the line of calling for sedition against the Moon government, callint it illegitimate, and demanding an immediate release from prison of President Park Geun-Hye. Candidate 10 was an ideological competitor for minor-party votes with Candidate 7; the latter got many more votes.

_________________

2018: Rallies

On the ground in Seoul in June 2018, I made a point to seek out political rallies. Surprisingly, the easiest traditional street rallies to find were for those supporting Candidate 7 or related movements. Candidate 7 is the right-wing anti-North Korea, anti-Moon hardliner, the energy of which is partly a defection from the Establishment-Right when it caved in over the Park Geun-hye impachment.

The real purpose of the rallies, nominally for Candidate 7 for Mayor, was was general-ideological. They were an attempt to make a move against the “Candlelight Coup d’Etat.” Far more were supporters than voters.

An example of what I mean by how easy it was to find Candidate 7 supporters is that I ran into them (and only them) on the subway, and got a picture to prove it:

In the distance is a banner with In Ji-yon’s name, but the general type of rally is already evident by the conspicuous use of the South Korean national flag.

Shortly thereafter, on the same day as I spotted the ralliers on the subway, I spotted a different group of supporters of impeached and jailed President Park Geun-hye (nominal supporters of Candidate 10):

These are Park loyalists from a group called the President Park National Salvaton Federation.

In the last image, you can see a banner with a U.S. flag at center, Park Geun-hye at left, Donald Trump flashing a thumb’s-up at right, the Korean national flag to Park’s left, and the Israeli flag at Trump’s right. Downright confusing messaging.

From my perspective and observation of events as they happened — and I was in as good a position to observe them as anyone in America, at a graduate school surrounded by Korea Watchers and Koreans — the pro-Park holdouts were not wrong in their basic analysis of the situation. A palace coup occurred, one of many in Korean history.

Given the weak turnout at that particular daytime rally, given the high average age of supporters, and given the radical message (their slogans imply they reserve the right take extra-legal means to resist the ‘illegal’ Moon government), it’s hardly a surprise that Candidate 10 got the fewest votes of all, one-third the level of the rival Dissident Right, Candidate 7.

I saw another rally, or rally of a sort, which was underwhelming in its energy-level despite the candidate getting orders of magnitude more votes. I’ll describe it later in this essay.

The night before the election, I came across, again by chance, a major rally of Candidate 7 supporters, at Shinchon, near the subway entrance. Their showing was impressive. It looked like this:

Looking at the stage, I think that is mayoral candidate In Ji-yon herself in the white cap. Her jacket (“7”) has her name on it.

The unmistakable signs that this was a late-2010s-era right-wing rally were the conspicuous number of Korean national flags alongside the U.S. flags. This trend only began during the Candlight Movement. Realizing they’d been outmaneuvered and fearing pro-North Koreans had seized power, they turned to the politics of Deus Ex Machina: “The U.S. will save us, if we wave the U.S. flag.”

The rally organizers here chose a provocative place for the rally, Shinchon street on a summer night with tens of thousands passing in all directions on the way too or from restraurants, bars, etc.; I think I was in the area specifically looking for political activity, and didn’t expect to find a rally of this kind at Shinchon, of all places. The midday Jonggak “Free Park Geun-Hye” rally of a few days earlier, I understood. But Shinchon in the evenign? bold. I wandered through the rally, and, despite the U.S. flags, I am confident I was the only White American lingering around this rally. I may have spent about twenty minutes in the area, observing.

Here is a video from late in the rally:

Another scene from near the general rally area:

Wandering out a ways, rally supporters were all over the vicinity:

I was bold enough to get near this van (I think there was more than one in the general rally area) to see what kind of people were hanging around it. It was not a surprise to see a “Release President Park” t-shirt guy at this rally, but it is maybe surprising that the t-shirt is in English:

Shinchon is one of the places you are relatively more likely to see obvious foreigners — and as I write this I am aware that it was their intention to get people exactly like me to see them, hence the U.S. flags and the English lettering on the “Release President Park” t-shirt.

Circling back to the core rally area, here are two shots I got of foreigners are passing through (I can only imagine what they ‘made’ of this rally):

_______________

2018: Banners and slogans

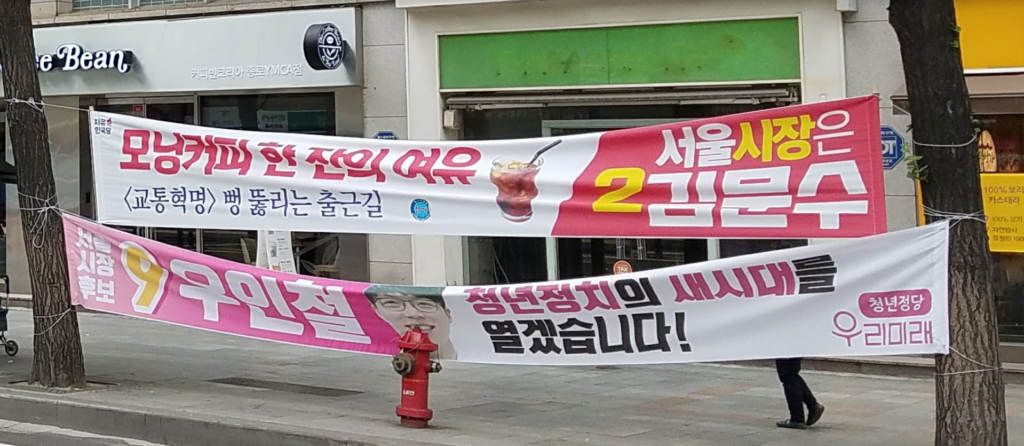

Two slogans from Establishment-Right candidate Kim Moon-soo’s team and from minor-party candidate Woo In-chol:

One of Kim Moon-soo’s main campaign slogans, about giving people extra time in the morning to drink coffee by speeding up the transportation system, seems particularly anodyne. I remember the experience of observing it at first, and of puzzlement at not getting what it meant (He is in favor of coffee? What is this?).

Ahn Chul-soo’s slogan was also not very ambitious:

Then there was the success of the Green Party’s candidate, who used the party as one of convenience, running a campaign entirely devoted to “Feminism.”

I give this much space to the minor parties of 2018 partly because they were so active and partly because their rhetoric (freed up to be more purely ideological, by merit of having no chance to win) signals where the Establishment parties go.

The Green Feminist’s candidate’s campaign is an example. It represented a moderate political frenzy wave in the late 2010s which led to sitting mayor Park Won-soon’s suicide. (The cause of the suicide was some kind of byzantine sexual-harassment scandal being alleged.) Other leading figures were also taken down in the same fashion in the late 2010s, including Korea’s leading poet, Ko Un.

Here was one from Hongik University area, surely a core base of support area for the “Green Feminist” if there is any:

Other banners for Candidate 8 included slogans that seemed to phoning-it-in for animal rights. But the majority of the rhetoric was specifically Radical-Feminist:

This one calls for an “anti-discrimination law” and promises to “oppose hate and fight.” This is disambiguated at the bottom: She wants Gay Marriage.

In some parts of Seoul, embarrassingly large banners were produced that covered sides of large skyscrapers, impossible to miss. Here is one I got a picture of, a candidate for head of Mapo District Office (in blue, rear left), covering most the side of a seven-storey building, but there were some much bigger ones:

Also visible are assorted other candidates’ banners, including:

- Kim Moon-soo (Candidate 2)’s “ChangeUp!” slogan (rightmost, top);

- One of “Green Feminist” (Candidate 8) Shin Ji-Ye’s slogans, “Starting with Seoul, sexual discrimination, OUT!” peppered with ’emoticons’ (right-most, bottom);

- Right-wing Candidate 7’s conspicuous use of the national flag with the giant slogan, “Save Liberal Democracy!” (left-most, bottom).

___________

The Place of the 2018 Mayoral Election in History

On the 2018 Seoul mayoral election, Park Won-Soon’s easy re-election, I do not recall much excitement one way or another.

The election must be understood for what it was: An opportunity for preexisting political forces to manifest and make a showing of arms, so to speak. That is why the no-chance minor-party candidates seemed strangely, somehow, more active than the actual major candidates.

It was also a dry-run for the presidential season of 2022 (lately fixed to early March by court ruling, after some confusion on dates due to the irregularly scheduled 2017 election).

Finally, given that June 2018 was not a Seoul mayoral election alone but a nationwide election for local officers, it was a dry-run for the National Assembly election, scheduled for April 2020 (destined to be greatly disrupted by the Corona-Panic).

A common refrain throughout 2017, 2018, and 2019 was the Establishment-Right party had nothing to offer. Their lackluster result in the June 2018 mayoral race signaled this belief was widespread. Since establishled narratives were largely confirmed, there was not much of a story. Dog Bites Man.

_____________

2018: Lack of Excitement

I think a typical non-Korean-speaking foreigner in Seoul could be forgiven for not even knowing there was a mayoral election, specifically, going on.

Four days before the election, I was at the British ambassador’s residence for the yearly summer gathering of the Royal Asiatic Society. I recall little discussion among those present of the ongoing election despite how soon it was. This was a highly talented and “in tune” group, but few were interested. Those who were interested waved it away as an inevitable incumbent victory.

______________

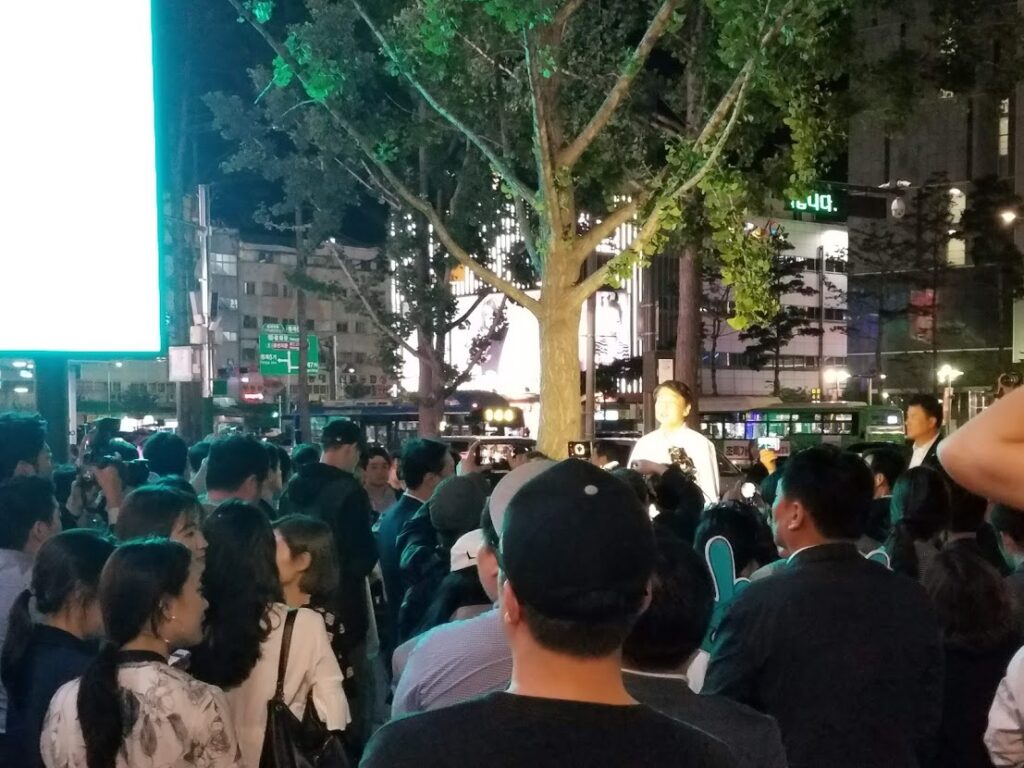

Reminiscence of a late-night street corner rally, June 2018

I have a very specific memory/experience of the June 2018 mayoral election campaign to record here.

In the late evening, the night before voting day, I was with A.P. (SAIS, 2017) walking near Dongdaemun (the name meaning “Great East Gate,” formerly the prestige entrance from points east into the royal city, now synonymous with a large market and downscale shopping opportunities). We saw a crowd gathered at a large, open area near the side of the street; A.P. did not notice it. There is always some commotion somewhere in a place like Dongdaemun. I noticed it, and soon noticed who it was. It was Ahn Chul-Soo [안철수], businessman, minor celebrity, and by then perennial political-candidate.

I was on the lookout for such things and had been for years, but in Spring 2018 I had written a long, well-received paper analyzing the South Korean political party system and its evolution after an electoral reform in 2004, so it was particularly relevant. I didn’t expect I would see one of the leading candidates himself, right there on the street. But so it was: Ahn Chul-Soo.

Ahn was not expected to win. People were mainly interested to see if he could beat the main center-right party’s vote total, and if so by how much.

Here was a late-night Ahn Chul-Soo street-corner rally on or about election eve. It was pretty underwhelming, and yet it stands in my memory even 2.5 years later. It had attracted a few dozen. Presumably because of a rule against loud noises at night, Ahn’s megaphone was turned down to a very low setting. From a stone’s-throw distance, we could not hear anything. I wandered in close and it was still hard to hear. A man with a good speaking voice could do better sans megaphone than this megaphone turned-way-down thing, which just looked ridiculous. Ahn was standing on a box and looked, or looks in my memory, very alone. He did not have determined-looking supporters on his flanks, as usually done for such visuals. He seemed alone and tired.

The spectators, milling around in my memory and some only seeming to half-listen, were unusually subdued for an election-eve political rally. A handful led cheers but few of the other millers-around bothered echoing the cheers. It was all somewhat a sad sight. A lot of these people were simply gawkers, like me.

I wandered away after a few minutes, and after about a minute’s walk there was no way to know anything was going on at the street corner in question.

Digging back through my June 2018 phone pictures, I was not able to find it. It stays with my in my memory.

Update (Jan. 6): I was able to find it. Here it is:

I was both surprised and delighted to have had this experience. To just wander across such things was a real gift, and the kind of experience that gave me an advantage over those who observe from afar.

I don’t think I have otherwise been in the near-presence of Ahn Chul-Soo before or since. As I say, I had written some about him in my politics paper, submitted just a month earlier.

A.P., who is Korean, was cautious, and for some reason would not approach too closely, but was indulgent with my curiosity as I wandered in close and got the above picture. There were a few dozen people there.

I could sense, after that few-minutes’ experience, that Ahn was definitely going to lose. Not only lose, he would probably under-perform the optimistic expectation that he would edge out the center-right candidate. Sometimes you can get a feel for such things by single-moment experiences.

_____________

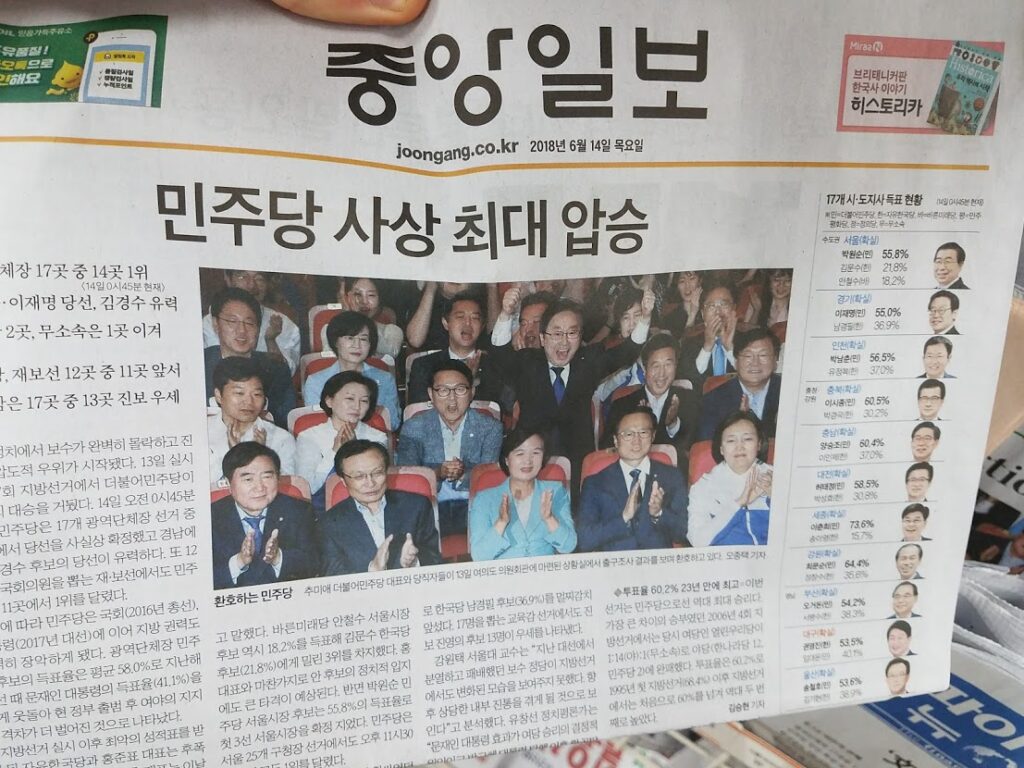

2018: The Results

The front page of the leading newspaper Joong-Ang Daily the day after the election described the result as a “Landslide, Unprcedented Victory for the Democratic Party.”

The Democratic Party had won elections in traditional conservative strongholds, with the Establishment-Right party winning only in the traditional stronghold of Daegu and North Kyongsang.

The Dong-A Ilbo used the same phrasing, adding that “Conservatives lost their way…Historic Landslide for the Ruling Party”:

As for the Seoul mayoral election alone, my impression that Ahn Chul-soo would underperform was right. While the early report, printed in the Joong-Ang Daily, put Park at 56%, his final tally was rather lower, 52.8%:

- Park Won-soon, of President Moon’s party, won clearly with 52.8% of valid votes cast, on a reported 60% turnout.

- Ahn Chul-Soo got 19.5%.

- The center-right party‘s man, Kim Moon-soo, took 23.4%, a clear, four-point win over Ahn, which is what they hoped for.

- Of the minor parties (which took an aggregate of 4.3%, largely pure protest or hardline-ideological votes), the two important stories are:

- (1.) On the Left, the Radical-Feminist candidate, much discussed above, edged out the main traditional Leftist candidate (the Justice Party);

- (2.) On the Right, the Korea Patriot Party (the successor of which in 2020-21 is “Our Republic Party”) was much more active on the street than at the voting-booth, taking only 0.2% of votes but representing a large share of visible street activism (as also discussed much above; I ran into their rallies and activities multiple times over multiple days in multiple places).

A twist on the whole story here is that the Establishment-Right’s candidate in June 2018, Kim Moon-Soo, the man whose campaign promised extra time for a morning coffee to all commuters, the next year joined a rebranded version of the right-wing dissident Korea Patriot Party, which didn’t have the machine or prestige but did have the energy and fighting spirit. For reasons I don’t know, relationship did not last long and Kim Moon-soo didn’t stick around. The new party then changed its name again, the second name change in two years, to the Our Republic Party, where it stands today.

(Political science literature on South Korea which I came to read while in graduate school is critical of the tendency to constantly merge and split and merge and split and ‘rebrand’ with new party names, seemingly every few years; critics in the late 20th century dismissed South Korean parties themselves as usually nothing more than vehicles for single political personalities. This still rang true in the 2010s but was much less true than before, with many of the minor parties one saw on the scene in the 2010s really coherently ideologically driven. Previously, ideological movements were generally not only extra-parliamentary but operated without party structures; now they are still mainly extra-parliamenary but many more kinds of tendencies do have party vehicles — for as long as they last.)

Park Won-soon’s comfortable re-election was as an endorsement of the Moon administration, then at its 13-month mark since inauguration in May 2017. There is no doubt that Park Won-soon had coasted in on the embers of the Candlelight Movement of late 2016 and early 2017 which had also brought Moon into power. There is more to be said on that matter, for another time.

_________________

__________

Jumping ahead now to the:

2021 Seoul Mayoral Election

Ahn Chul-soo is a candidate again in 2021, the only personality from 2018 to make a second appearance.

There is the makings of another three-way race. The same rough split could repeat in 2018, with the same result. That would be a rather boring result.

The three-way split in 2021 is this:

- Ahn Chul-soo [안철수], vs.

- The Establishment-Left governing-party’s candidate Park Young-sun [박영선] (a former TV broadcaster, now minor cabinet member in the Moon government), vs.

- The Establishment-Right’s Na Kyong-won [나경원] (recently a leading figure of that party after the disruptions of the mid-late 2010s);

Another potential candidate being mentioned is former mayor (2006-11) Oh Se-hoon [오세훈], on whom more in the 2011 reminiscence, below. (I know someone, Jo. Du., a Canadian and longtime Korea resident, who for some reason intensely dislikes Oh Se-hoon but I have never been able to figure out exactly why.)

Here they are, in the order named, which is roughly the order of support:

The latest chatter is this:

Ahn probably wins is the Establishment-Right candidate (Na) endorses him. The Establishment-Right candidate probably loses if Ahn endorses her (a maneuver less likely to happen anyway). In a three-way race, the Establishment-Left candidate wins.

This kind of situation should call for a run-off between the top two vote-getters, but South Korea has no such mechanism.

Ahn has more support even within the Establishment-Right party itself than either of the two potential candidates from that party. (The Establishment-Right party is currently called the People’s Power Party [국민의힘당], a 2020 rebranding which copied Ahn’s own party’s name, the People’s Party [국민의당] — If you’re following this, or not, you now can appreciate why they have “Candidate Numbers” and not just “Candidate Name + Party Name.”)

I don’t know if any of these three are willing to speak publicly against the crazy Virus Lockdowns. A lot of politicians across the world became mired in a Demagogue Trap, suddenly spineless, unable to find the courage to resist the seeming witchcraft-panicking lynch-mob amid the wild, unprecedented social experiment of endless “lockdowns.” But that’s another story.

_____________

Returning to the subject of the dead-by-suicide mayor, Park Won-soon.

He had entered the scene nine years before his suicide. My mind goes back to that time, and to the:

2011 Seoul Mayoral Race

I have much less to say about 2011. But I do have some kind of connection to it.

When Park Won-soon won his first mayoral election (Oct. 2011), I had recently arrived (mid-September) in Bucheon. I was not particularly aware of what was going on in Korean politics. I was hardly aware that there was any election going on. Seoul Mayor Oh Se-hoon had resigned over a failed Aug. 2011 referendum. (I was not in Korea yet in Aug. 2011. Even if I was, at this stage I may have been only vaguely aware of this development.)

I had landed in a foreigner community in the north-end “new-city” portion of Bucheon, a year before before the subway opened in this part of Bucheon. There was still a strong foreigner community there, by merit of the connection to Seoul being somewhat more difficult, especially to foreigners, as it required a bus. Bucheon had two thriving “foreigner bars,” which would be gone by the end of the decade. The foreigners were mainly, but not all English teachers, as I was.

An alignment of circumstances made for quite a tall mountain to climb to get out of the “English-speaking Foreigner’s Trap,” a trap from inside which it was/is difficult to see out at politics except in the most superficial of ways.

I developed the drive to look outside the “Foreigner’s Trap.” Most others seemed stuck in it for the duration. (I recall one such representative case from within the Bucheon foreigners circle: After a year in Korea, this person could not even positively identify the full name of the country in Korean: Daehan-minguk. Had no idea what the term meant. Embarrassing, yes, but the phenomenon of the English-speaking Foreigner’s Trap in Korea is a complex one, and one ought not fault anyone for being in it, because it is not necessarily their doing.)

I would come to escape the trap, to some extent, in coming years, but was quite firmly in it as of late 2011. In this context this is all to say I was not well positioned to observe the 2011 Seoul mayoral election by merit of cluelessness and detachment from the society despite physical presence.

Bucheon, while not in Seoul, is effectively a (fairly) seamless part of the Seoul Megalopolis as it exists in the early 21st century. In any case the Seoul mayoral election is a big deal everywhere given Korea’s “politics of the vortex.” (That’s the often-chaotic process of sucking of all energies towards the center, towards the Seoul vortex. True in centuries past, true throughout the various political eras of the Republic of Korea, true today). To illustrate the point, the president as of 2011, Lee Myung-Bak had himself been mayor of Seoul just before being elected president.

I don’t recall specifics from the 2011 race for reasons described, but I do have some very specific memories of something too noisy to ignore (literally) at the time:

Throughout September and October 2011, there was an active “anti-Free Trade Agreement with the United States” movement ongoing. In Korean, the Korea–United States Free Trade Agreement was simply referred to as “FTA.” You couldn’t move about in public at this time without sooner or later encountering anti-FTA protests of some kind, often single people with bullhorns or teams of people doing something, causing noise. This anti-FTA movement was one in a chain of anti-U.S. movements over the previous ten years. It picked up a strand identifiable within Korean politics traceable back through many generations and circumstances back to the earliest era of peaceful relations in the 1880s.

I was teaching at this time. Teenage students were sometimes bold enough to endorse the anti-FTA movement. One boldly said that South Korea would become a “colony” of the U.S., of U.S. Big Business (or something) if the FTA went through.

(The actual results of the FTA were, if anything, that the U.S. side had larger relative losses and lesser relative gains, though free-market theorists would insist that both sides won, on net. Donald Trump, several years later, targeted the “KORUS FTA,” as Washington jargon called it, in his campaign and rhetoric.)

Park Won-soon was elected 53-46 on low 48% turnout in Oct. 2011, against Na Kyung-won (who is back, ten years later, for another shot, but unlikely to win). Seoul leans Left in any case, so his 53-46 win was now exactly a decisive endorsement, but he was in.

There was a legislative election in April 2012. By this time I remember taking an interest in it, making it the center of lessons in some classes in April, getting students to think/talk/write about it (see Post-66). I don’t think they did this in classes in school or elsewhere, but through the medium of a foreign language they might be more open. Then came the big Dec. 2012 presidential election.

________________

The 2014 Seoul Mayoral Election

The regularly scheduled Seoul mayoral election was back in June 2014. Park Won-soon won again by the exact same margin as in the Oct. 2011 special election, 56-43, this time on 59% turnout.

This election was less than two months after the Sewol ferry accident which killed off most a graduating high school class and others on the doomed vessel. The left-wing opposition, including those quite supportive of North Korea, used the disaster to attack the (right-wing) president with success, something I found distasteful at the time but which seemed to have staying power.

I was back in Korea — in Songdo, Incheon — by the time of the 2014 Seoul mayoral election, too busy (at this time studying Korean, at the start of the long arc of my graduate school) to worry about something as far off as the Seoul mayoral election. I have no specific memory of the campaign or election, but the Sewol incident can only have guaranteed a Park Won-soon victory on account of his being of the opposition Democratic Party.

________________

Bonus Reminisce: Why Was Park Geun-hye Impeached?

The idea that Park Won-soon’s 2014 mayoral election win was because of the Sewol disaster, which preceded it by mere weeks, leads me to a tangential reminiscence. Why not?

In summer 2017, I had a long conversation with my friend J.H. (a Korean born in 1978; family name: J. [정], given name: H.). One forgets the contents of most conversations almost immediately. Some stick with you for years, and this, for some reason, is one of the latter.

We were talking about the then-recent impeachment of President Park Geun-Hye. I cautiously brought up that I didn’t think the whole thing was exactly fair or above-board. He allowed himself to, speaking to me in English, break what was effectively a taboo at this time: He said he agreed that it wasn’t fair. He implied she was railroaded. He implied sending her to prison made no sense. This all took me by surprise because I knew J.H. was not a supporter at all of Park Geun-Hye’s, but also not necessarily a hardline ideologue against her.

J.H. then said “Park would not have been impeached if it weren’t for the Sewol disaster.” “But she had nothing to do with that,” I responded. He agreed, but characteristically went into an elaborate theory on how Koreans are psychologically different from Westerners (by which he meant NW-European-origin Whites), saying Koreans are “emotional” whereas Westerners are “rational,” at least by comparison. It wasn’t fair, but it was inevitable.

What J.H. seemed to be saying Koreans demand sacrificial lambs. He was not saying this was a good thing, but that it’s just how things are.

Looking back through my June 2018 phone photos for material for this post, I see I took quite a few of the then-seemingly-permanent line of protest tents at Gwanghwamun which implicitly (sometimes explicitly) accuses the political Right in South Korea of causing the deaths on the Sewol. Here is how it looked the day before the election:

Mayor Park Won-soon had set up a policy whereby Gwanghwamun was effectively ceded to protestors, and no protestor there was to be touched. This eventually degenerated into Gwanghwamun becoming a permanent protest zone lined with permanent tents, really an eyesore. The one at right says, “Why didn’t you save them?” (the same tent has a cartoon picture of a whale with “Sewol” written on the side in English). Next is: “Government murderers! Save our children!” This mega-slander is seemingly such a histrionic overreaction that one struggles to understand it. J.H.’s theory fits the observable facts.

When I was in Seoul, I several times walked through these permanent-protest area, which I think became as substantial as it did only by 2016. The mood was tense, uncomfortable, silent, sullen. I had been at this same area in years past. It was open space, inviting to tourists. (In my first-ever trip into Seoul from Ilsan, my only male co-worker and confidante of the time, Lee J.S., advised me to go to Gwanghwamun.)

In the early half of the 2010s, probably 2012 or 2013 when living in Bucheon, I recall once or twice proposing to meet my friend Jared, then of Ilsan, “at the Yi Sun-shin statue.” It is there visible in background left. Central Seoul was about halfway, and Jared had a fondness for going to the big Kyobo bookstore nearby. The statue as a meeting point, to not miss one another, would not be possible by the late 2010s because of this protest tent-city.

Back to summer 2017 and J.H.’s theory on Korean (political?-)psychology. Granted that Park Geun-hye was not necessarily a qualified or good president, but her impeachment and imprisonment were ultimately because of something not her fault, a ferry accident with a large loss of life. (The impeachment came 2.5 years after the ferry accident, over an unrelated scandal involving an adviser.) I don’t know what this conversation’s denoument was, as my memory only locked in the initial exchange.

If one believes J.H.’s theory, about a spring 2014 ferry disaster directly affecting political events as far as late 2016 and 2017, one must likewise believe it affected political events as of mid-2014.

Observers back through the generations can be found remarking on the tumultuousness of Koreans politics, that political or quasi-political frenzies seem to “gust in” with regularity. I’ve observed a few. The Park Won-soon suicide of July 2020 was an unusual case. A suicide of a sitting mayor of a major city, Korea’s capital and (by far) leading city, was unusual even for Korea, though he did have the precedent of the ex-president Noh Moo-hyun suicide in May 2009.

_____________

Ahn Chul-soo as the “No Brand Man” of South Korean Politics; Looking ahead to 2022

It’s funny to think that President Moon Jae-In is already near to being a lame-duck, given the one-term limit on the presidency. Fourteen months left until the next scheduled presidential election. Much the final two years of his term look to be disrupted by the Coronavirus Panic of 2020-21. (I expected fresh initiatives with North Korea in 2020, but they haven’t come.)

If Ahn Chul-Soo wins as Seoul mayor in April 2021, which he may well, he is a strong contender for president, with the next presidential election set for March 2022.

This may be so much over-estimating of Ahn’s chances. People have been doing this for ten years, ever since he started in politics to much fanfare.

How does one understand Ahn? Starting in the mid-2010s, there has been a line of products and then stores (and now, for some reason, fast-food hamburger places) in south Korea marketed as “No Brand,” originally a line of the in-house products of the E-Mart big box store, I think. Ahn Chul-Soo has always marketed himself the same way, has tried to cultivate an image as the “No Brand Man of South Korean politics.”

Being the No Brand Man means, in theory, he could take supporters from Left and Right and also among the Non-Political or Disengaged, just as he has from the start (see Post-71).

At one time, Ahn had singificant youth support among the b.1980s and b.1990s cohorts. That was in the early 2010s. Ahn has headed a party that branded itself as Centrist for most of the past five years.

The “No Brand Man” image never quite worked, and many Koreans confided in me, when I pressed them for views on Ahn in late 2010s, that they “used to support him but he disappointed them,” or some close variant of that. I recall people born in the late 1980s and early 1990s specifically saying this.

The political “No Brand Man” has been less successful than the “No Brand” line of products — and the implausibly successfully No Brand Burger fast-food chain (the slogan of which is “It’s Good Enough”). But he is still around, and his chances look better than ever.

Another thing about Ahn I can say is that he swims just below the surface of international awareness, by which I mean vaguely Korea Watching circles in Washington, who in my experience largely indifferent and unaware of South Korean domestic politics.

Here is a man who was even talked about as a serious Seoul mayoral candidate in the 2011 special election (he didn’t run), was a major candidate in 2018, and now also in 2021. (In the 2014 mayoral race, he probably would have run but was a sitting member of the National Assembly at the time and so had other concerns.) So this is no obscure figure of interest only to academics or specialists. But I can say from experience that even someone with fairly good knowledge of South Korea, observing from abroad (by whch I mean Washington and maybe New York), can be excused for not even knowing who he is.

I worked with people at a Washington think tank in 2019 who styled themselves semi-experts South Korea. I am rather sure the several people I’m thinking of don’t know who Ahn Chul-soo is. If they ever learned the name, I am confident they did not store the knowledge, but promptly chose to eject it from their brains for lack of relevance.

Relevance is fast approaching:

If Ahn is elected Seoul mayor in April 2021, or even comes in a strong second, his campaign for president in March 2022 will have begun by default. The political cartoon that opened this essay has a specific reference to this:

Ahn is shouting: “Gather ’round!!” He holds a sword labeled: “Entry into Seoul mayoral race.” His yellow sash says: “The Anti-Moon Federation.” He stands on a mountain-top called “Political Support,” with winds conspicuously blowing with the usual metaphorical meaning. In Ahn’s back pocket is a second sword, labeled “The Presidency.”

The presidency is of course the bigger story, which will finally put Ahn’s name on the map for general-interest English-speaking audiences, especially if he wins, which looks at least possible now.

One thing I’m not sure at all about is what the North Korean regime-party would think about Ahn Chul-soo finally rising in South Korean politics, potentially to the presidency. They have a long game-plan, and are in relatively better position today than at any time since the 1980s.

Ahn Chul-soo’s entire appeal is that he is not an ideologue and not attached to any of the big political machines with historical baggage (the “No Brand Man”). But if he does win the Seoul mayoral race, and then the presidency, it will be from votes from a lot of right-wing opponents of North Korea in addition to his theoretical base of Centrists.

But first things first. The April 2021 Seoul mayoral race is fast approaching.

____________

[End]

[Updated morning Jan. 5 and morning Jan. 6.]