Tomorrow is May 16th. On

May 16th, 1961, a clique of army officers, led by Generals Chang Do-Young and Park Chung-Hee ‘invaded’ Seoul and declared martial law.

A few weeks later, the coup was hailed as “the finest thing that has happened to Korea in a thousand years” by American General Van Fleet, known as the “Father of the R.O.K. Army”.

This single action largely defined South-Korean politics for the next thirty years or so. Its reverberations are still being felt into the 2010s. The daughter of General Park was elected president in 2012.

I will attempt here to give a brief outline of what I have learned about the coup during my time in Korea.

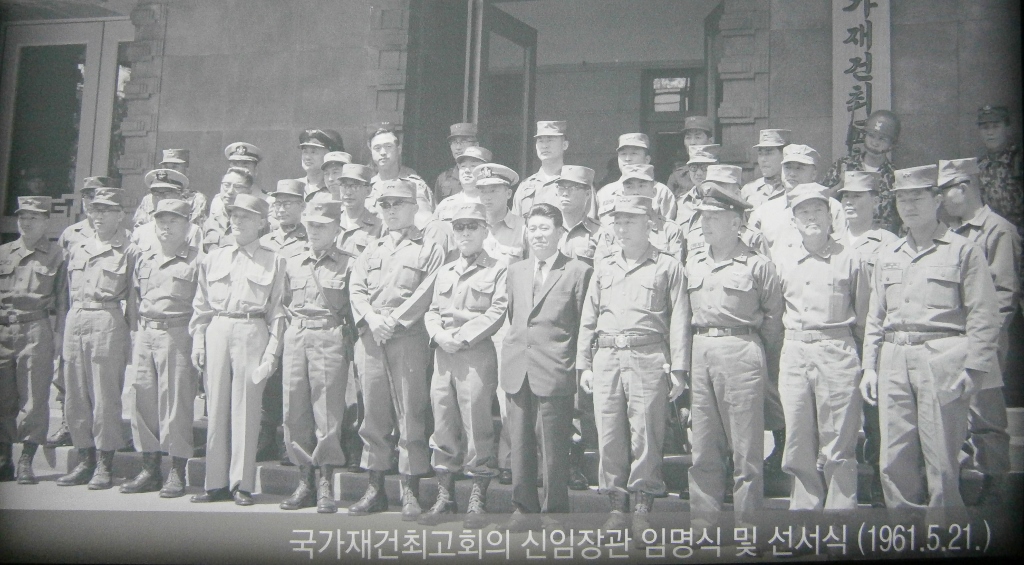

Posing in Front of Seoul City Hall on May 16th, 1961

General Park (left, with MacArthur-style sunglasses) and other officers

It was 3:30 a.m. [on May 16th, 1961] when the Jeeps and trucks loaded with soldiers began rolling into Seoul. At the Han River bridge, six confused military police guards made the mistake of resisting and were shot on the spot. Columns of marines and paratroopers raced unopposed to the center of the city, surrounding government buildings, blocking intersections and firing into the air to frighten the populace.

One squad headed straight for the Bando Hotel to arrest Manhattan-educated Premier John M. Chang, whom the army expected to find asleep in his eighth-floor suite. But Chang and his family slipped away a few minutes before, and were already safely hidden at a friend’s house.

When dawn came, the coup was complete. Seoul seemed almost normal but for the heavy guards at every intersection and the orders blaring over the radio from the headquarters of peppery little Lieutenant General Chang Do Young [장도영], 38, Chief of Staff of the 600,000-man ROK Army, who now declared himself “Chairman of the Military Revolutionary Committee.”

Proclaiming martial law, General Chang ordered the Cabinet arrested, halted all civil air flights, banned political parties, forbade meetings and decreed censorship for newspapers.

General Chang Do-Young [장도영] and General Park Chung-Hee [박정희] (right)

pose in Seoul on May 20th, 1961, four days after their successful military coup

Over the next days, Generals Chang, Park, and the others explained why they had seized control of the government:

John M. Chang [장면],

John M. Chang [장면],

Leader of South Korea from

August 1960 to May 16th, 1961

(1) To oppose Communism in all its forms

(2) To root out corruption

(3) To solve the misery of the masses

(4) To transfer power to new, conscientious politicians

The pursuit of (1) led to the arrest of thousands of Koreans suspected of “pro-Communist plotting”. This included many former government officials, including the former leader John Chang, on the pretext that he had given $770 to a left-wing “relief society”.

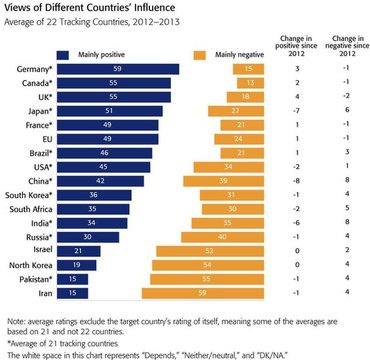

I suspect that this “opposition to Communism” as front-and-center was to win American support. General Van Fleet’s comment (the title of this post), and the subsequent acceptance of General Park by the Kennedy administration, suggests this was a success.

The larger goal, though, seems to have been the pursuit of point (2) above. This led to the arrest of many more, tens of thousands if not into the hundreds of thousands (40,000 in the first five months). People were arrested for anything deemed degenerate by the junta (e.g., prostitution, smuggling, scamming, gangsterism, running suspicious nightclubs, printing of ‘slanderous’ or leftist newspapers…and so on). Some of the worst offenders were executed.

The junta tried to ban conspicuous-consumption itself. Elaborate weddings and funerals: Outlawed. A waste of resources. Only simple ceremonies from now on. Wooden chopsticks: Banned. A waste of wood. And any government official who showed up five minutes late for work was fired on the spot. Hard austerity, it all was.

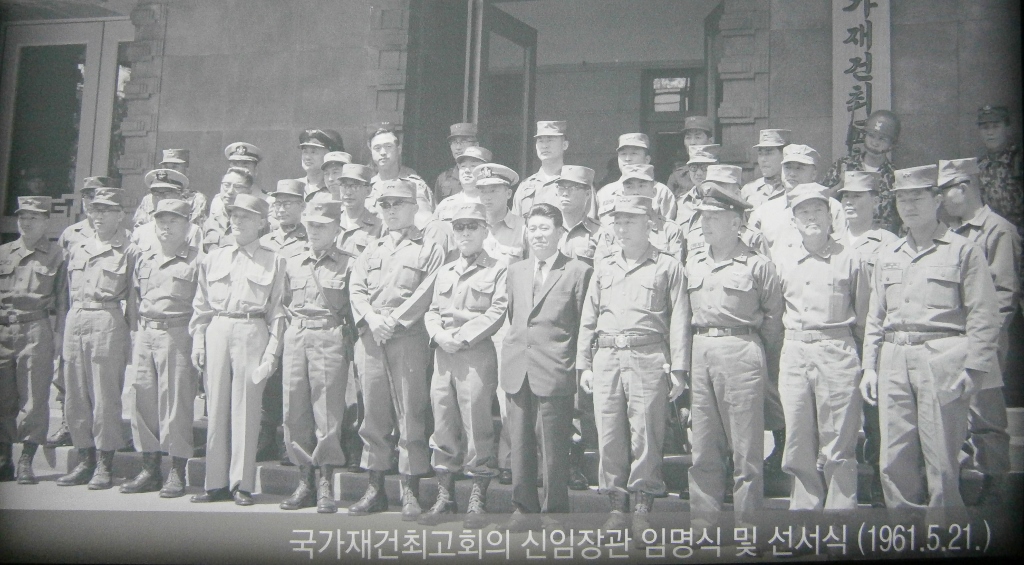

Officers that took part in the May 16th Coup pose on May 21st, 1961.

The shorter General Park Chung-Hee is standing, hands behind his back,

next the tall and sunglasses-wearing General Chang Do-Young, in front center

The promised “new, conscientious politicians” turned out to be heavily drawn from…the Army, presumably including many of the men in the group photo above. In certain ways, this was a good thing: They were a talented bunch. General Paik Sun-Yup [백선엽] wrote the following in the epilogue to his war-memoir:

After I let the army, I was posted as Korean ambassador to R.O.C. (Taiwan) for a year, to France for four years, and then to Canada for four more, returning to Korea in 1969. I found that Korea had been surging ahead economically since 1964, guided by an infusion of managerial knowledge provided by people who had served in the ROK Army.

One ROK-Army veteran with a lot of managerial knowledge (Chief of Staff in Spring ’61, in fact) was soon out, though:

Chang Do-Young [장도영]

Chang Do-Young [장도영]

General Chang (born 1923), the head of the junta in the early weeks, ended up arrested him

self, in July of 1961, and was not heard from again. Few Koreans remember him today.

Ever since I learned this story a few years ago, I’ve wondered what became of the “peppery” Lieutenant General Chang Do-Young, the defacto ruler of South Korea for a few weeks in 1961. Did he return to the army? That would’ve been awkward. Did he live quietly on a farm for the rest of his days?

In fact, Chang spent time in Seodaemun Prison after his arrest, and released in 1962 or 1963.

After that, he actually went into a kind of exile in the USA. He had studied English in Japan during World War II, so he could speak English. He earned a doctorate from the University of Michigan in 1969, and became a professor at the University of Wisconsin until 1993, when he retired. He died in 2012. [From Korean Wikipedia]

It was General Park who ended up president, a position he retained until his death in 1979.

Things began to relax in 1962 and 1963; many prisoners were pardoned. Soon economic growth picked up.

Most Koreans who actually lived through that period (of military rule) seem to remember it fondly, it would seem. The coup and the subsequent strength of the Park Chung-Hee government brought an end to the instability and stagnation in which South-Korea was mired since its independence, many say. General Park is given credit for the wild economic growth of the 1960s-1970s. He was killed in 1979, but the essence of the regime he set up lasted well into the 1980s. Other generals, drawn from the broad-circle around Park, took his place after his assassination. The final general-turned-president handed over power to the first non-military president in February 1993.

Most negatively, the coup can be waved-away as s a power grab by ambitious mid-level figures in the military.

Most positively, it can be seen as a successful attempt to eliminate corruption/backwardness, resulting in prosperity.