Part VI: Meeting My Affable PredecessorIf you’re reading this, you may or may not have read Parts I to V

. Or you may have gotten a bit tangled up in the digressions therein (and Part V was entirely a digression). This is ostensibly a narrative, though, so

on with it.

Around the Table Again

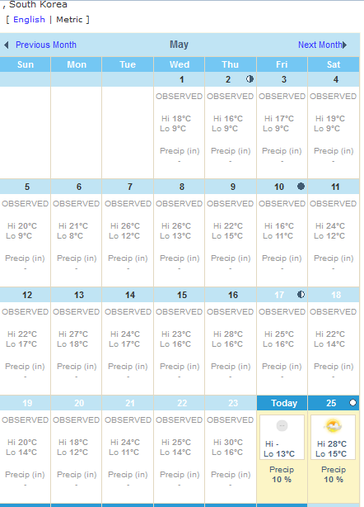

Back on April 29th of 2009. A small, not-well-lit, noisy restaurant, after 11 PM. Conviviality is thick in the air, though less so at our table. Ours is a bit tense, you see, because it’s hwe-shik (as described in Part V). I sit at a corner of a wooden, rectangular table around which sit seven others. Six are Koreans. One of them is “B”, an affable American man in his mid-30s. I sit to his right.

B is my predecessor. His contract is up. He is going home. I’m taking his job.

Looking to my left, I see B, but beyond him I can see the regular Korean teachers. There are four of them (Kang, Yoon, Im, Lee). All are half-curious to see the new guy (me). I tried to describe the ambiance of their side of the table back in Part IV. Also (possibly) present, at that far end of the table and furthest away from me, may have been at least one of the so-called “Desk Teachers” (a curious title that was used for the two front-desk staffwomen. A “desk-teacher” was a receptionist/secretary/miscellaneous-job-doer, not a teacher at all). My memory is foggy on whether any desk-teachers were there, but at most hwe-shik the later-shift desk-teacher was generally also present.

Across from B sits Mr. C, the Korean husband of Mrs. Y, my new boss. Mrs. Y herself (whom I described in Part III) sits down directly across from me as I take my place next to B. That rounds out this review of the cast of characters.

Mrs. Y, the boss, is still all smiles, as she was to be all night. She promptly orders more alcohol, as was her wont to do. It was probably beer, although soju materialized soon, too. She didn’t ask if I wanted any. “Alright, this is the way it’s going to be” was more characteristic of her approach. My impression is that this is expected of the boss in Korea.

Some of my talking was with Mrs. Y and Mr. C, the bosses. We talked about lots of things, including the hagwon (language institute). They set me straight that it was an English hagwon, not a general-purpose hagwon which included English (as I’d read some are). That is how ignorant I was — I didn’t even know the nature of the job I was walking into. Mr. C was interested in the decline (and “bailout”) of the U.S. automotive industry, which was big in the news at the time — The nation that had pioneered car manufacture now had a bankrupt auto industry. One of us made the comment that the ones who pioneer things are often not those who do it best.

Naturally, some of my conversation was with B. I learned we had two things in common: He had a Danish surname (as is my own) and he was from Iowa (as is my father). Other than those two facts, he was quite different from me.

Physical Description of My Predecessor

Physically, B was 6’0″ or so, same as me, but a bit on the plump side, perhaps about average for a 21st-century American. I later learned he had gained weight due to a weakness for fried-chicken, a South-Korean obsession.

Later, too, the top student at this hagwon, then a 9th-grader who had scored an amazing 104 points on the TOEFL iBT test, told me various things about B, not all of them good. One of the stranger comments he made was that B “looked like Homer Simpson”. I had not seen it. The student commented that B’s “huge eyes” caused the resemblance, which, again, made no sense to me. Did B have “huge eyes”? I hadn’t noticed. The “big eyes”/”double-eyelid” beauty ideal in East-Asia is accurate, but comparing someone with big eyes to Homer Simpson does not seem complimentary!

The Affable American‘s Amazing Reading Ability

With the conversation flowing, food and drink came and went. New dishes were needed to replace those eaten.

That’s when it happened: The boss asked B what they should order next. He obliged. He went line by line through the simple menu, commenting on what he thought was good, recommending things to the boss. There was not a single English word in sight on that menu. He recommended pa-jeon (파전), which we ate.

I was stunned. There B was navigating through this seemingly-indecipherable alien script. And so seamlessly! How could a White man read an East-Asian alphabet? Put crudely, that’s something like how I felt. Maybe “impressed” is the best word. In time, I developed the magical ability to read it, too. It’s not as impressive as it seems.

I soon learned that the alien script that B was able to read was called Hangul (officially, hangeul [한글]), and it is a high-point of pride among Koreans, who developed it seventy years before Luther hammered his 95 Theses onto that door. [Note: “Hangul” definitely refers to the Korean script, or “alphabet”, which in sentence form looks something like this: “피터선생님 멍청이 아니에요”. There seems to be a persistent mistake among those affiliated with the U.S. Military regarding this word. They seem to call the Korean language itself “Hangul”, which is definitely wrong. When I visited my uncle in 2011 at Camp Casey (he was there for work), more than once I was asked by his associates, “Can you speak Hangul?”, which logically makes no sense. It seems to me that’s like asking, “Can you speak hieroglyphics?” / My cousin’s husband, Air Force, stationed at a base in Korea in 2012, whom I visited in February of 2012, also repeated this erroneous use of the word “Hangul”.]

Good at Playing the Game

That B could read Korean (i.e., Hangul) more-or-less well was a testament, perhaps, to his status as a veteran of ESL in Korea. He had several contracts under his belt by the spring of 2009. Another was ending that very week.

He was smooth, on the charming side but without a hint of smarminess. He knew how to play the game well. He knew how to make himself look good to the Koreans without working too hard. I’ve always felt I am the opposite: I work (“too”) hard but don’t put much effort into making myself look good to superiors. My attitude is that it is immoral to do the latter, whereas it is “moral” (somehow) to produce quality work without overt desire to personally benefit. I am suspicious of (what I perceive to be) “form over substance” types. B was, looking back on it, somewhat of a “form over substance” person, frankly. (Sometimes I think Korea itself runs on a “form over substance” basis.)

B was well-liked by students and the Korean teachers. However, the kids who liked him tended to the lazier ones. In other words, he wouldn’t push them much. The kids who liked me most tended to be of a different stripe altogether.

Much later, I happen to have come across B’s resume at work. I think he completed four contracts through April 2009, with several-month gaps in between each. B was one of those who would do a year or so and return to the USA for a few months, visit friends and family, perhaps travel, and live off his savings, then return to Korea to do another contract. This is mostly my conjecture, but what else would he have been doing in those months?

My Predecessor’s Predecessor

Much later, too, I learned that B had only been at this ‘campus’ of the hagwon for a few months, after transferring from the other ‘campus’. The other campus (in the Hugok neighborhood of northern Ilsan) was bigger, and was managed by Mr. C — which is why Mr. C was here at this dinner. Why had B. been transferred so late in his contract? It turns out the previous foreign-teacher had done some damage. The mothers were upset. B was called-in, in the same way as a steady veteran pitcher is brought in when the bases are loaded in the ninth inning.

The guy he replaced: A younger American, G., lazy and sarcastic. I never met him (as he left in late 2008 or early 2009), but I did learn this much: G. dedicated his preparation time in the teachers’ room exclusively (so I’m told) to giggling at political-comedy videos on the Internet, probably John Stewart. Hardly any planning was done; all of G’s attention was given to John Stewart. His classes were incoherent at times; his tests were lazily made. This guy was there about six months, from when this campus opened. The boss, Mrs. Y, did not like him. She liked B a lot more.

Although G. had not been gone long by the time I arrived, no one ever really referenced him a positive way or said they missed him. Many missed B. It was hard, for me, to step in after a popular teacher (B) left.

A Check In the Mail

In the two days I knew him, B gave very little guidance on actual teaching, but helped me in lots of other ways: He gave me his electronic bus/subway card, onto which I could load money in the machines. He drew a map of places I’d need to find my way around, he showed me how to get the bus to the hagwon. He also left me three boxes full of coins. Their cash value was something like $200. In a year or more, he’d never paid in exact change. He’d always overpay and take change home. He said he ran out of time and asked if I could go to the bank and send him a check to a U.S. address in Illinois. Okay. A few weeks later, I counted the money and sent him the check. It was quietly cashed. I never heard from B again. I heard my boss speculate that he was back in Korea, as of 2010.

*******************************************************

This is all getting ahead of myself, though. Back on April 29th, I was drawn to B, because he was the only other native-English speaker in sight. I’m glad they sat me next to him. But, then, where else would they have put me?

I was also intrigued to be sitting across from Mrs. Y. The thing is, I didn’t at that time know what to call her. I didn’t know her name. Knowing her name wouldn’t have solved that problem anyway, as it turns out. . . .