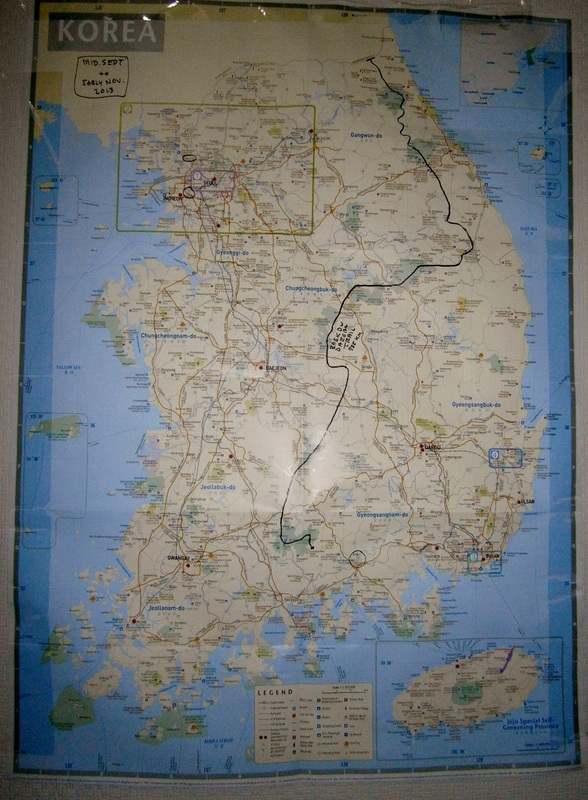

I recently visited the battle site of Chipyongni, a three-day siege in February 1951 during the Korean War, when 5,000 Americans and French defeated 25,000 Chinese attackers. It was first successful defensive stand for the Americans against the Chinese in the Korean War.

I mentioned my visit in post-148 (“the Gettysburg of Korea“). I wrote:

In 2012, after reading “The Longest Winter”, I identified the location of the battle by figuring out its current name. What we wrote in English in the 1950s as “Chipyong” is now written as “Jipyeong” [Gee-pyuhng] (지평리 in Korean). Its suffix, ri or ni, means “village” in Korean. It has since been promoted to “myeon”, a slightly larger settlement than a ri/ni. The current name is thus Jipyeong-myeon (지평면).

[…] [Visiting the site] was one of the most significant excursions of my time in Korea. I feel blessed that it worked out the way it did. The word “Chipyongni” does not even appear in the tourist guidebook I have. It was something I independently discovered.

Below is the location of Chipyongni (now called Jipyeong-myeon, 지평면). You can zoom-in on this map all the way. It is anchored on the site of the memorial, which is in the middle of the American defensive perimeter.

Across the Country By “Subway”One of the amazing things about this excursion to Chipyongni is that I covered 95%+ of the distance to the battle site (the red marker above) using what is loosely called “the subway”. It has evolved into a cheap-and-easy Greater Seoul Rail Network. It has been gobbling-up legitimate (above-ground) train-lines for years, and continues to expand. There are now about twenty lines. I wrote about one such rail-line way back in

post-9:

This rail line [“Gyeong-Hui”] still exists intact, today, It was incorporated into the ever-growing Greater Seoul urban rail network (still often loosely called a ‘subway’) in 2009. I remember when that happened, as I was living in Ilsan at the time, through which it passes.

I also rode the “subway” very-long distance to Chuncheon this year. See

post-15. This most-recent Jipyeong-myeon/Chipyongni trip is another instance for which sarcastic quote-marks on “subway” are called for. I scanned-in with my transit card at Bucheon (west of Seoul), and stayed in the system all the way to Yongmun, the terminus of the “Jungang Line”. The trip involved 80 minutes of riding Line 7, then waiting around to transfer in east-Seoul, then another hour on the Jungang Line until Yongmun. The total cost for the subway trip, as the screen told me when I scanned my card out of the system at Yongmun, was an incredible 2,150 Won (less than $2.00 USD[!]). As you can see above, this was a trip near halfway across the country, east-to-west. The trip was not very pleasant, though, as I had to stand for almost all of those three hours, and it was generally crowded all the way. At $2.00, it becomes a

“don’t look a gift horse in the mouth” thing. South Korea is no longer a cheap place to live, but it still for transportation.

Yongmun Station, September 2013

Yongmun Station, September 2013

At YongmunSaturday. Sometime before 10:00 AM, my traveling companion and I arrive at Yongmun Station, tired, groggy. For an “end-of-the-line station”, the atmosphere outside is downright “kinetic” this morning, though. Koreans in hiking gear are frolicking about. They are probably all going to the Yongmun Temple area.

In the 850-page travel guidebook on Korea I have, this entire region (Eastern Gyeonggi-Do) gets about a page and a half’s write-up. All that is mentioned is Yongmun Temple and its environs (“Yongmun-sa [temple] sits below Yongmun-san [mountain]. At 1,157 meters, this mountain is not the tallest in Gyeonggi-Do, but some say it’s the best-looking. Of its many hiking trails, the one that’s perhaps most often used goes over the….”). A few resorts are also mentioned.

In that guidebook, the word “Chipyongni” appears nowhere., though.

Eastward On Foot

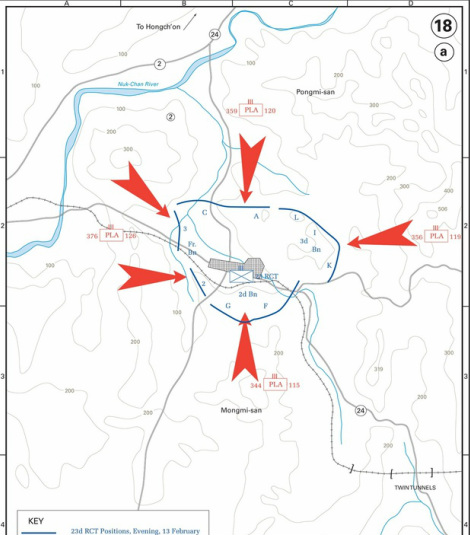

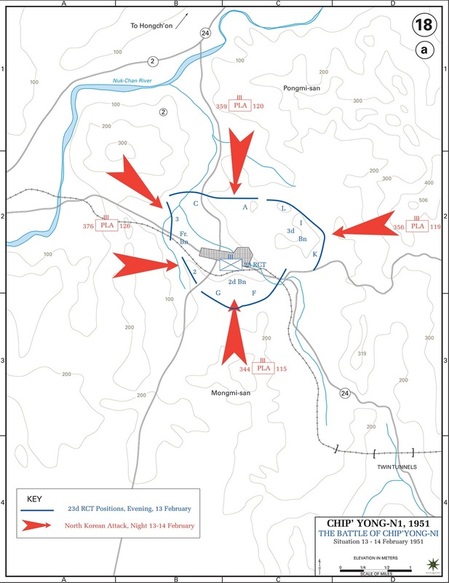

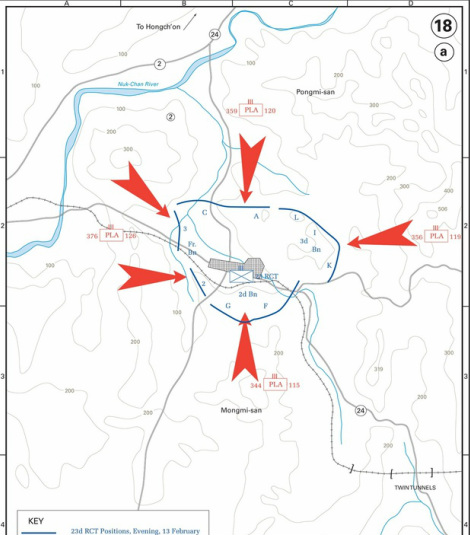

The original idea was to get out of the train station at Yongmun and proceed to Jipyeong on foot, only three miles away. I carried printouts of the battle history, downloaded from history.army.mil, which I read again on the train ride. Included was the following map:

Map of Battle of Chipyongni. Red are Chinese [PLA] attacks. Blue are U.S./French defensive positions.

Off to the west, along the railroad tracks and just off the map, is Yongmun Station. [See

post-147 for battle history]

My idea was to use the landmarks on the above army-history map to try to find the U.S. and French defensive positions during the siege and walk along them. They defended low-lying hills around the village. I had little idea as to how I would find those exact hills. I just sort of hoped it would work out. I didn’t have any clue if there was any kind of memorial or anything.

Walking through the town of Yongmun, we got some kimbap and a disappointingly-small plate of tteokpokki (떡볶이). Heading east towards Jipyeong, I saw a ROK Army base:

The entrance to an army base in the town of Yongmun. [Click to expand]

I couldn’t help but chuckle at the fact that this Korean Army base includes several “cute” things, a cartoon soldier with the word “Last Punch” (I don’t get it), and a yellow smiley-face on the sign.

Minutes later, we were out of the town, and came upon this kind of scenery:

Scene between Yongmun and Jipyeong [Chipyongni], South Korea [September 2013]

This is the kind of thing that the veterans of the Korean War must remember, at least during autumn. It’s not how it looked during the Battle of Chipyongni, though, as the battle was in frigid February. Temperatures were below freezing and snow was on the ground. Walking through in the pleasant fall weather, and with the drenching-humidity of summer in very recent memory, it’s hard to imagine that this landscape will become “Siberia” in a few months. It will.

On to the Memorial

A snag in my ad-hoc plan presented itself after a while. It was necessary to cross a narrow mountain pass, but construction workers were obstructing it. We turned back. A taxi passed by, and we got in. I marveled at this good fortune. A taxi passing by such a road was lucky, exactly when it was needed. The friendly driver drove us the few miles to the Chipyongni Battle Memorial, dropping us off in front of the below sign. The ride cost 5,000 Won ($4.50).

Sign pointing out the “Record Stone of the Jipyeong Battle” [지평전투전적비]

The old tradition in Korea is to mark an important event with an inscribed stone. This was done for the dramatic battle of Chipyongni by a ROK Army division in 1957. That stone still stands. I later heard from a local resident that it used to be nearer the town hall, and was moved out to its present location some years ago. Both locations may be arbitrary when it comes to actual place-significance for the battle. The locals we spoke with later said this, something I’d already suspected. Here is the map, again, zoomed in. The red marker is the location of the battle memorial:

As best I can tell by

comparing the maps, the American defensive perimeter in the north ran in a line from the larger of the two little blue lakes in the top right of this map, and straight west from there. It ran a bit west of the creek, then turned south, which was the French position.

Here are some photos of the memorial:

Chipyongni Battle Memorial [September 2013].

At the top of the stairs sits the “record stone”. The UN flag, ROK (South Korea) flag, U.S. flag, French flags fly.

Another view of the record stone and flags. In the background on the right, construction has begun on a new museum

A view from the top of the hill that houses the record stone, looking southwest.

The village of Jipyeong [formerly Chipyong] is off to the left in the distance.

Museum Under Construction

The building shrouded in blue will be a new museum. I found this sign in front of it:

Sign informing visitors that a new Chipyongni Battle Museum is being built, and will open in 2014.

(Locals were skeptical it would actually open then due to lack of money.)

Me looking at the plaque

Me looking at the plaque

The sign above says the cost of the museum project is 1,761 백만원, or $1,761,000 (if I converted that correctly), and that it will be completed on January 30th, 2014. The cost is being paid 50% by the army and 50% by the state. There will be two floors, one an education hall (교육장) and the other an war-exhibition room (전시관, I am not sure of this translation).

I spent a long time at the memorial. I read every word, though I already knew the history from my previous reading on the subject. As I hope the above pictures show, the atmosphere at this memorial site is very pleasant. There were no other visitors or passersby in the hour or more I was there, though I did see one construction worker.

After leaving the memorial site, we walked south to the heart of downtown Jipyeong. Here it is. I don’t know why there is a woman dressed in old-fashioned garb:

“Downtown Jipyeong”: The only major intersection in town

Again,this is right in the center of the village, the most significant intersection. There were very few cars around.

The red banner there says “우리도 죽기전에 지평면에서 수도권 전철 타고 싶마”. I recognized enough words to understand that it was a slogan demanding that the Seoul urban rail network be extended to Jipyeong Station. It currently ends one station before Jipyeong, at Yongmun. This is a major inconvenience for Jipyeong residents. If they want the ultra-cheap way to get into and then around Seoul (see above), they have to go to Yongmun first. They can still ride the “normal trains”, but those are much more infrequent and more expensive. Maybe a bigger reason for this campaign is to put Jipyeong “on the map”. To Seoul-area dwellers, Jipyeong doesn’t exist. If it’s on the subway network, suddenly it exists, and more people would visit, and would spend money. These banners were all over Jipyeong.

Here is a wider shot of the intersection:

That blue structure is a bus-stop. About the time I took this picture, I was approached suddenly by a boy. He said something like “I have never seen a foreigner here before!” I think those were his first words. He spoke in English. His grammar and accent were both great. I asked if he’d been abroad, and he said he’d been in the Philippines. He informed me that he was in middle school, and he said the town had only 100 students. I don’t know if he meant 100 in the middle school, or if 100 was the total for the elementary, middle, and high schools combined. I could believe the latter. He wondered what I was doing. The boy was eager to please, so I asked him for help in my quest to walk the hills of the battle. I showed him my map print-out, and asked if he knew how I could find any of those hills. He puzzled over it for a while, trying to orient himself. Soon, a small gaggle of friends had joined him. Nobody knew anything. One girl identified “Pongmi-san” on

this map, but nobody had heard of “Mongmi-san”. They wandered away.

This boy’s warm conversation, and (futile) attempts to help, was the first of many instances of kindness from Jipyeong people that really impressed me (the taxi driver was first, but he was a Yongmun person, I think. He undercharged me, knowing I was a foreigner visiting this historic site). Random “street” kindness to strangers, especially foreigners, is quite uncommon in Korea, and this boy’s kindness amazed me. Never once in Bucheon, in two years, has anything like this happened to me.

Continuing on, I resolved to try to find where the railroad crosses the major road east of town, that being where the 23rd Regiment’s 2nd Battalion was entrenched, according to the army-history map. I never made it that far. Walking a short was east, I found a town-hall. I had the idea to look for a map, but it was locked up. A bunch of men were loitering outside an adjacent building, and invited us in to eat. It was a dining hall. Before we knew it, this happened:

A free meal served by “New New Village Movement” (새새마을) at Jipyeong town hall, September 2013

Those tin-foil spherical objects are “rice balls” with a few other ingredients tossed in. This is commonly called “fist rice” (주먹밥). There are also side dishes (반찬) and fried mushrooms. All free. This was the second instance in which I was amazed at the Jipyeong people

‘s generosity and hospitality. We weren’t entitled to this food, being non-residents. Again, in my experience in Korea, you

don’t invite strangers in such a way as this, much less foreigners. (I mean, hell, in two years we foreign-teachers were never invited once by the boss[es] of the language-institute to dinner). This was an event organized by a civic group that I presume offers free lunches at the town-hall every Saturday.

So the guys standing outside the town-hall insisted we should eat this free food. Bottled water was also given freely, and there was even beer. The man in the blue baseball cap in the above photo came over and talked to us for a long while. He insisted on sharing some beer. The subject turned to the battle. The man consulted my map (this one), but held it upside down. He talked at length, my Korean friend reported, about the site of his house and how many Chinese were killed in its vicinity. He said he’d been in the USA in 1988, while in the ROK military. Another local, a man with tied-back hair who greatly resembled an American-Indian to me, also sat down, mostly quiet (his taciturnity added to the “American-Indian vibe”). He was clearly interested and wanted to help.

Soon the man with tied-back hair asked if we were interested in the small museum about the battle. It was housed in the nearby library. We were. It wasn’t open. The man with tied-back hair said to wait a minute. Minutes later, the man returned, and led us to the library adjacent to the eating-hall and the town-hall. He’d gone to fetch the octogenarian Korean-War veteran museum-caretaker. He asked him to open it on account only of us! The old man had kindly come in, and was waiting. I couldn’t believe my good luck to meet such people as these. (This kind of hospitality puts Seoul and its satellites, like Bucheon or Ilsan, to shame. It made me think, “I hope this place fails to get its train station incorporated into the Seoul Metrorail network”, for fear it would be corrupting.)

A small room constituted the Chipyongni Museum:

The small “Chipyongni Museum” housed in the Jipyeong Library.

Its caretaker is in the background, with a red cap, emphasizing some point

I spent a long time here, looking at everything carefully, and listening to the man speak. He had a lot to say and was highly enthusiastic. He is a veteran of the war, and I presume he is from Jipyeong. This is his museum.

There is Korean War paraphernalia of all kinds, uniforms, helmets, equipment salvaged from the battlefield, badges, portraits, photographs, books, maps, and binders filled with photos of the various commemorations over the years. Every year, he told us, a French delegation arrives to honor the French battalion. Descendants of the American veterans also come every year, he said. The man informed us of various fine points the history of the battle (it involved only 300 Koreans, “KATUSAs” embedded in the U.S. Regiment and the French battalion, he said), of the village (it has not really grown much since 1951), of the museum (the new, larger, museum [see above] supposedly opens in 2014, but he doubted it would), and the preservation efforts (he said there was talk of making some or all of the defensive perimeter into a marked hiking path. It would be two miles long or so). This man has documented a lot about the battle. I get the feeling that the new museum, next to the memorial, may have been his initiative.

I noticed the guestbook on the table. When I visited on the afternoon of September 7th, there were no names in it yet for September. In fact, the previous entries were on August 20th, and prior to that, August 11th. I leafed through all the pages, going back to early 2012, and found only a small handful written in English, and those belonged in all but one case to U.S. Military personnel. They wrote their “address” as “Camp Humphreys” or the like, nothing more. There may have been about five military who visited. There was a single non-military foreigner in the past year, the man recalled. He said she was a middle-aged woman from Texas visiting her daughter who was teaching English in a nearby city. He described her.

I signed the guestbook, leaving my name and address.

The museum keeper of Chipyongni

The man, at one point, criticized young Koreans for their anti-Americanism. He became a little more animated. He was apparently saying that they are ungrateful and spoiled. This is characteristic of his generation’s attitudes. The younger generations were fully ready, a few years ago, to believe that U.S. soldiers had deliberately murdered two Korean middle school girls by running them over with their tank during an exercise

for fun, even (or so goes the lie) backing up several times over them to ensure the girls were dead. These U.S. soldiers were animated solely by hatred for Koreans, many believed or claimed to believe. Then, they were tried in a U.S. military court and found not guilty, further evidence of American disregard for Korean life! (The court found the incident to be a tragic accident, and determined that the girls were walking in a strictly-restricted zone that day). That Koreans really believed the storyline as presented above is baffling. I attribute it to the “follower” mentality. No, it’s not rational, but others are saying it, so we’ve got to follow. That story probably literally originated with North Korea. It’s the kind of thing they

do. The protests against U.S. beef of the late 2000s, and then the protests against the FTA of the early 2010s were equally ridiculous, the museum-keeper commented. (U.S. beef is still not being sold in South Korea in my experience.)

At the end, the kind and energetic man gave me two pamphlets about Chipyongni in English and Korean, and a medallion that says “We Will Not Forget / Battle of Chipyong-Ni” and something in Korean.

After leaving the museum, we walked to the train station to get tickets on the “normal train” get back to Bucheon, with the intention of also finding some of the other historical markers the kind old man at the museum had discussed.

Another act of unprovoked kindness followed at the train station. The attendant said no seats were available, but that we could come back later and maybe some would open up via cancellations. Someone in Seoul or Bucheon would’ve just sold us “standing tickets” (the same price, for some reason, as sitting tickets) and been done with it. This man, though, waited, and constantly monitored the status of seats available via his computer. He tracked us down outside the station an hour or more later and said he’d reserved the tickets. We paid. We rode back to Seoul that evening in seats, and fell fast asleep (having woken up at 6:00 AM), which would’ve been impossible with standing tickets. Why did this man go so far to make our trip more convenient? He gained nothing from it. These Jipyeong people are amazing, I concluded.

Before leaving, I found a few more historical markers. The French memorial is near the train station:

The French Memorial, near the French Battalion’s headquarters during the battle (according to the museum-keeper).

Memorial stone for the French Battalion at Chipyongni, in French, Korean, and English. [Click to expand]

We ate a small dinner at this spot, on the grass.

I suspect that these memorials were set up by the Americans because of the grass. Both here and at the main battle memorial (discussed above), the grass is of the softest kind you often find on American front-lawns, not unlike my memories of my mother’s front lawn from years ago, so soft it’s more pleasant to lay on than a bed.

Judging by my comparison of the current map and the battle-history map, this was probably the above was about the view the French soldiers had as the Chinese approached and attacked.

One curious thing during this visit to Jipyeong was the butterflies. They were everywhere. I captured one in a photo:

A typical sight in Jipyeong during my visit

Finally, the train came through at 6:09 PM, and about six people got on at Jipyeong Station, myself included. The train was already packed, having started way down in Andong, but we had seats due to the vigilance of the attendant.

Jipyeong Station

Minutes after settling into the train seat, I fell asleep. I awoke in Yongsan, central Seoul, and hour later, amazed at what a great day-trip I’d just had.